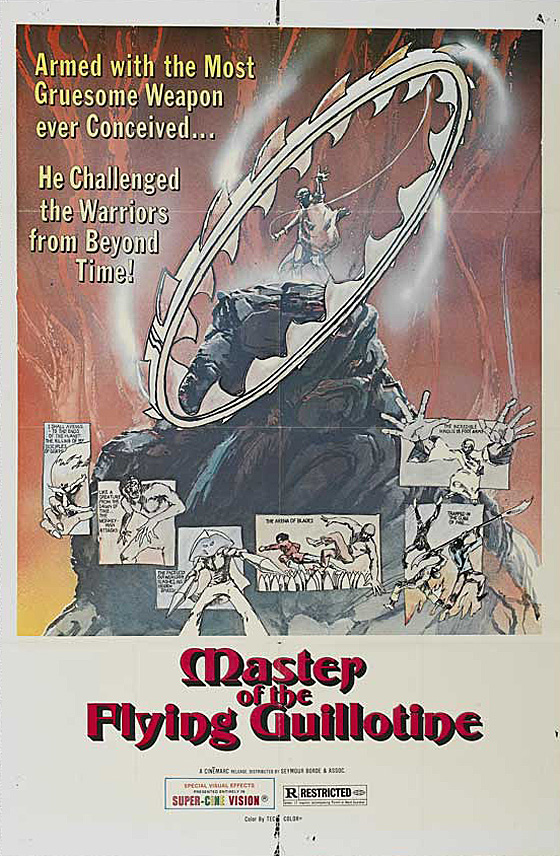

There’s a moment in Master of the Flying Guillotine (1976) that shows us its cards, beautifully. A one-armed drunk has wandered into a spacious tavern. While stuffing his mouth with food, he smashes seven flies at once: “Seven in one blow!” he exults. A few minutes later he’s boasting to the tavernkeep that he’s a mighty one-armed warrior and “today I killed seven in one blow”; from the upper landing, the ears of an old blind man prick up. He’s been on the trail of a one-armed warrior, and this may be the man he seeks. He opens what appears to be a red hat, razor blades lining the inside snapping into place. He hurtles it over the landing, and it clasps a net around the victim’s head and neck. The old man jerks the chain attached to the hat, and the one-armed drunk collapses headless to the floor. No blood spills from between the shoulders, though the dummy’s severed neck is painted red. If his “Brave Little Tailor” story of seven-in-one-blow doesn’t make it clear enough, his surreal death drives the point home: this is a fairy tale. Albeit a Chinese fairy tale, of the wuxia & martial arts variety, with warring clans, noble heroes, and cunning villains. Like so many Chinese fairy tales, it’s rooted in history. The film takes place during the 18th century, as the current emperor of the Qing Dynasty, Yongzheng, has rebel supporters of the previous Ming Dynasty hunted down by assassins wielding these hat-like “flying guillotines.” (The weapons themselves were a real device, and even recently featured on Mythbusters.) One of the emperor’s assassins, the blind Fung Sheng Wu Chi (Kam Kang), receives word in the opening scene that two of his disciples have been slain by a man with one arm (Jimmy Wang Yu, The Chinese Boxer), as seen in the earlier film, The One-Armed Boxer (1971). He sets out to have his revenge.

Wu Shao Tieh (Doris Lung) and the One-Armed Boxer (Jimmy Wang Yu) discuss plans to stop the Master of the Flying Guillotine.

The One-Armed Boxer has been teaching a martial arts class in a village, where his students are also dissidents against the current emperor. Much of the film consists of a martial arts tournament which the boxer and his students attend as spectators. As contestant after contestant enters the ring, the film settles into a hypnotic series of over-the-top duels; I’m reminded that films like these set the template for video games like Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat (as they punch and kick, the same two thudding sound effects are repeated over and over, as though someone is tapping the A and B buttons on a Nintendo controller). Helpfully, each contestant has a nickname which describes their fighting technique. “Flying Rope” Chao Wu has a rope; “Tornado Knives” Lei Kung has many knives; “Iron Skin” Niu Sze has impenetrable flesh (like “Brass Body” in RZA’s The Man with the Iron Fists); “Braised Hair” Cheung Shung Vee has braided hair that can strangle his opponent. One battle takes place on the tops of poles stuck in the ground over deadly sword blades, while the opponents try not to lose their footing. When Wu Shao Tieh (Doris Lung, Brave Girl Boxer in Shanghai), daughter of tournament president Wu Chang Sheng (Yu Chung-chiu), steps into the ring, she uses each blow to strip her opponent, until he’s sprinting naked and bruised out of the arena.

The Eagle Claws Tournament: two contestants battle above sword blades stuck into the earth.

The tournament is interrupted by the flying guillotine, decapitating yet another one-armed man who isn’t the One-Armed Boxer. (This grants us the amusing sight of an actor with both one arm and his head shoved under his shirt collapsing to the ground.) Now alerted to the assassin’s presence, our hero retreats to his school with his students, but before he can organize a plan of defense, he’s drawn into a fight with a Thai “foreigner” (Sham Chin-bo) aiding Fung Sheng Wu Chi, before the blind man himself comes sailing through the window; there’s quite a lot of jumping through walls and rooftops in this film. The final battle is delayed – the One-Armed Boxer successfully escapes – because there are still more of the assassin’s henchmen to dispatch. Each battle is another breathless setpiece. Most memorable is the Boxer’s fight with the Indian assassin Yogi Tro La Seng (Wong Wing-sang), who not only can summon sitar music on the soundtrack, but can elongate his arms like Plastic Man. Their battle, with his awkwardly swaying arms, looks like something directed by Jim Henson. In one of the film’s most creatively staged scenes, the One-Armed Boxer and his Merry Men set a trap for the Thai bruiser, trapping him with the protagonist in a hut surrounded by fire (his attempts to escape out the window are blocked by the students’ jutting spears). The barefoot fighter finally succumbs to the searing-hot floor, while the One-Armed Boxer, protected by his shoes, leaps out of the hut to cool his feet in a bucket of cold water. Satisfyingly, he can only take out the Master of the Flying Guillotine using all his resources: a clever scheme (bamboo is involved), fast moves, and some gravity-defying footwork (he can climb walls and hang from the ceiling).

The Master of the Flying Guillotine, Fung Sheng Wu Chi (Kam Kang), lets fly his blade.

The film was not just a sequel, but an entry in a specific subgenre of “flying guillotine” movies, preceded by the Shaw Brothers’ Flying Guillotine (1975); there’s also The Fatal Flying Guillotine (1977), Flying Guillotine 2 (1978), and The Vengeful Beauty (1978), among others. A similar weapon threatens James Bond in Octopussy (1983) while on a trip to India, but, sadly, the assassin does not elongate his arms. Much of the credit for Master of the Flying Guillotine‘s endless charm can go to its star, Jimmy Wang Yu, who also wrote and directed. By 1976 he was already well established as a star of martial arts cinema, though not without notoriety in both his professional life (legal troubles arose after breaking his contract with the Shaw Brothers, which exiled him from Hong Kong to Taiwan) and his personal (an unusually tumultuous love life, as well as other personal scandals including a murder charge in 1981, later dropped). Here, he plays straight to the audience’s Id, delivering on their expectations in spades. Master of the Flying Guillotine is a pure martial arts movie. There’s a minimum of complicated exposition, a wealth of characters and fighting techniques, a pounding soundtrack (sampled from Kraftwerk, Neu!, and Tangerine Dream), and inventive choreography with a surprisingly smooth integration of special effects. It’s proof that nonstop action in a film can avoid being dull provided there’s a steady supply of imagination – and humor – in the mix.