To avoid fainting, keep repeating, it’s only a movie (in a movie)…

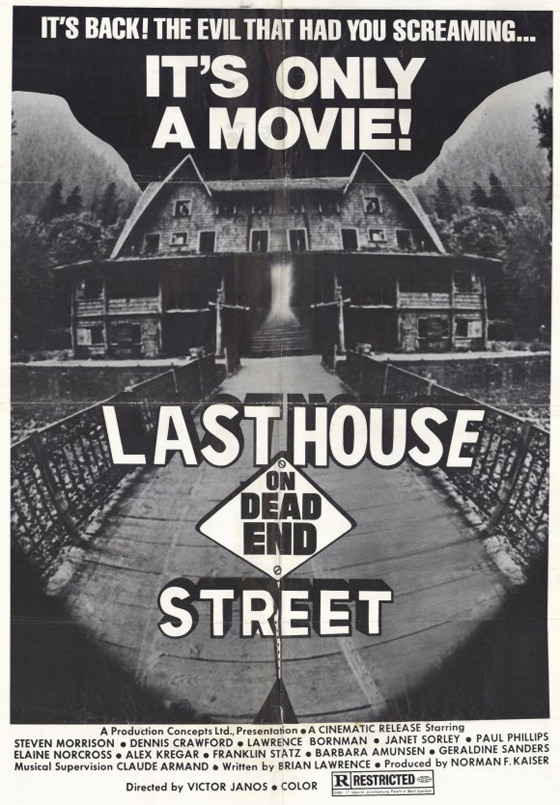

That wasn’t its tagline, but should have been. Last House on Dead End Street (1977) obviously owes its title to Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972), which is a film that I don’t particularly like but will admit is a landmark of its kind. Dead End Street‘s distributor encouraged the comparison right down to the poster, which made it sound like a sequel: “It’s Back! The Evil That Had You Screaming…It’s Only a Movie!” What both films have in common is a gang of vicious young adults who torture and kill, their actions depicted at excruciating length. But Last House on Dead End Street was not, as you might have guessed, its original title; its shooting title was, appropriately, At the Hour of Our Death, and the first cut of the film reportedly bore the title The Cuckoo Clocks of Hell (this particular cuckoo clocking in at nearly three hours, which does sound hellish). It was filmed in 1972 but not released until 1977, at a more reasonable 78 minutes. That’s when its legend began. The film was more horrifying and nihilistic than Craven’s film; Craven’s was inspired in structure by Ingmar Bergman’s (infinitely superior, and just as harrowing) The Virgin Spring (1960), a fable of rape, murder, and bloody retribution, but Dead End Street doesn’t bear such a shapely narrative arc. It’s more of a line slanting downward, right off the precipice. But what’s more, it’s a metaphysical film, with a commentary on the act of viewing horror films that’s as visceral as anything out of Michael Haneke’s oeuvre. These killers are even more crazed and scary than the ones in Craven’s film, and perhaps that’s because they’re filmmakers.

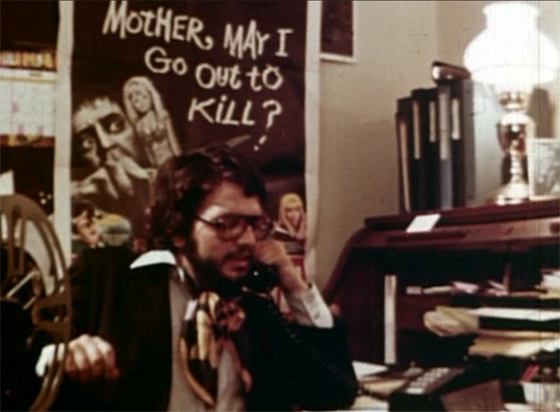

Pornographer Steve Randall (Steve Sweet) in his office, a poster for the Freddie Francis/Robert Bloch Amicus film "The Psychopath" hanging behind him.

Our central character is Terry Hawkins, a bitter psycho in a leather jacket, fresh out of the state pen after serving six months for a drug-peddling sentence. His thoughts are delivered to us in mumbling voice-over while he smokes and wanders empty streets (the film was shot in upstate New York) under grim-looking skies. “I’ll show ’em. I’ll show ’em all what Terry Hawkins can do…I think I’m ready for something that nobody ever dreamed of before.” While distorted choral music plays, we see gruesome images of a screaming, bloody woman and a disemboweling – ugly promises of scenes that are yet to come. “I want to make some entertainment for all my friends. I want to take care of all those people who been takin’ care of me for all these many years.” We see him reuniting with old friends: a young female vagrant who likes the sound of his new movie idea, and would love to participate; a cameraman with bad skin and bags under his eyes who agrees he’ll film whatever Terry has in mind; and a hustler named Ken who recommends he check out this woman named Nancy Palmer, who makes pornos with her husband Jim for a sleaze merchant named Steve. Terry tells Ken, “Nobody’s interested in sex anymore. They’re looking for something else.” And Terry’s the one to give it to them.

A member of Terry's film crew dons her mask.

We visit the Palmer residence for one of their swinging parties. Nancy’s in her bedroom applying makeup – hang on, that’s blackface. She heads downstairs, strips down to lingerie, and bends over while a man pretending to be a hunchback whips her. (More disturbing: the young boy who’s present.) The bourgeois spectators laugh and applaud while Nancy winces in agony, and Steve, in sunglasses and clearly bored, smokes from his chair. Nancy’s husband Jim listens from upstairs, in evident discomfort. Eventually Steve joins him; they watch some of his stag films, and Steve is critical. He wants something that moves faster, something exciting and innovative and edgy. The next day, Terry shows up. Nancy doesn’t know him, but when he says he’s a friend of Ken’s, she agrees to fuck him. Afterwards, he shows her a film he and his friends have shot of an old man being strangled. “It looks so real,” she says while they lie in bed. “They’re supposed to, aren’t they? That’s why they sell…I’ll let you in on a little secret, if you promise not to tell anybody. They look real because they are real. It looks like I strangled him because I did strangle him.” “That’s not funny,” she says. “It’s not supposed to be funny,” he replies. Then he confronts her: she and his friends took credit for one of his stag films, cutting him out of the profits. He rapes her. We see Steve in his office, receiving a phone call from Terry; he’s being invited to a meeting in an old abandoned building. Shots of gargoyles, the sound of thunder. Steve arrives and climbs stairs into the attic, a vast and dark interior. Spotlights suddenly blaze on. Terry and his friends emerge from holes punched into the drywall – his movie set. One of them is holding a camera. Terry’s girls are wearing transparent Halloween masks. The Palmers are tied up, and so is a blonde acquaintance named Suzie. Terry’s movie is now underway.

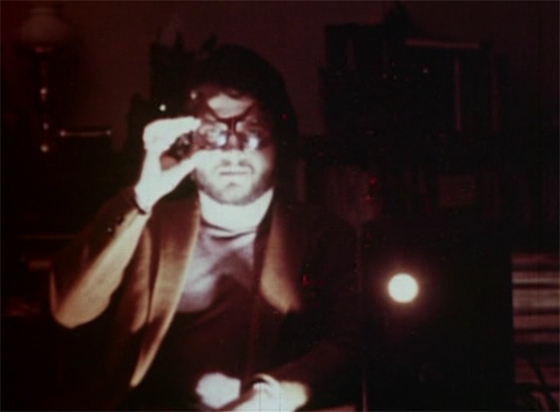

Terry Hawkins and his gang.

What follows is forty straight minutes of hallucinogenic torture and slaughter. Terry wears a large white mask that looks like some Greek god: Hades, perhaps. The sound of a beating heart thumps on the soundtrack, and occasionally that creepy choral music. Dialogue is repeated over and over so it becomes increasingly meaningless, but also hypnotic mantras: Terry…the answer…his virgin bride…will all be natural… Later, after some bloodshed, Terry turns his sights on porno director Jim Palmer, asking the terrified man to direct his cast. Some of his thugs do a demented can-can in a shot that reminded me of Pasolini’s Saló (1975). Then there’s a new mantra, delivered with screams and spittle by the increasingly unhinged Terry as he attacks poor Jim with an Al Pacino-style rant: “I’m directing this fuckin’ movie! I’m directing this fuckin’ movie!” Nancy meets the most terrible end of all, tied to a table and covered by a sheet in a faux hospital set, the gang now dressed in surgical masks and uniforms; painted on the wall behind her are Rocky Horror-style lips marred by two rows of sharp teeth. Her face is cut up, her legs are sawed off, and when she passes out, she’s roused with smelling salts. Then her belly’s cut open and bloody viscera is held up to the camera. In the film’s most inexplicably disturbing sequence, Steve is confronted by one of his female torturers, who removes her top, unbuttons her fly, and reveals a severed deer hoof jutting through the opening. He’s forced to put his mouth on it in a bizarre obscene gesture, while another girl positions two other hooves behind her head like horns. After another chase, Steve is tied up, and the spotlights are turned on him once again. The killers gather, trading masks, then slowly approach the camera (we are now firmly lodged in the victim’s POV). Terry doesn’t say a word. He holds out a power drill and drives it through Steve’s eye. Then, with no one left to torment, the figures retreat slowly into the darkness behind the movie lights, while we remain watching from Steve’s seat. One man wipes his bloody hands distastefully on his shirt. Credits roll, but not before an unconvincing message from a disembodied Dragnet voice that the members of Terry’s gang “were all later apprehended.” Oh good.

Nancy Palmer (Nancy Vrooman) is tortured on Terry's hospital set.

The film shocked grindhouse and drive-in audiences (who were expecting some Last House on the Left-style cheap sicko thrills, but not this) before slipping out of the public eye. As it sporadically resurfaced in different edits – some more graphic than others – fans obsessively collected and bootlegged and spread the legend. Some rumors even suggested that this movie about snuff movies actually was a real snuff movie, an appealing notion only among those disappointed that the Mike and Roberta Findlay movie Snuff (1976) was not what the posters claimed. Certainly the mystery was stoked by the fact that the detailed credits are actually chock full of pseudonyms. The director was named “Victor Janos,” for example, a name that had no other credits. It was not until 2000 that the real Victor Janos stood up: a man by the name of Roger Watkins, who had made some amateur experimental films and hung out with Otto Preminger, Nicholas Ray, and Dennis Hopper before his feature film debut of Last House on Dead End Street. Watkins claimed he shot the film with money on loan from his father, most of which he wasted on meth and heroin during the shoot. Watkins himself played the wild-eyed Terry Hawkins, and the character may not have been too far from his real persona: he also shot some stag films (including the black-and-white film shown in Dead End Street; the actress sued over the use of the footage, which accounts for the film’s long-delayed 1977 release), and enjoyed dark and sadistic subject matter; though it was after shooting this film that he was lured into directing pornography, under the alias Richard Mahler. Watkins’ decision to come out of the shadows and take credit for this film allowed him to enjoy some of its revival success, and he recorded a commentary track for the (long out-of-print) DVD prior to his death in 2007.

Steve in his screening room.

In evaluating the qualities of Last House on Dead End Street, it’s difficult to avoid that it’s a grindhouse movie, with muddy sound, rough editing, and crudity, not just bad taste. Some scenes are completely superfluous, such as one in which two girls discuss whether prostitution is worthwhile. The screening of the stag film certainly drags, with awkward dialogue improvised by Steve Sweet, and the audience becomes aware that this is really just padding. (Perhaps the three-hour cut is only more of this.) But Watkins has an undeniable flair for images and montage. The second half of the film unfolds with sights and rhythms that are deliberate, ritualistic, and contain the electric feel of being authentically occult. I mean, those deer hooves – what the hell does that mean? Watkins at times seems to be channeling Kenneth Anger, with a touch of Jodorowsky and Arrabal. The final moments were as powerful to me as when I watched the finale of Saló. Which means that Last House on Dead End Street, though it contains elements of exploitation, does not feel exploitative to me, but infused with a real artistic purpose: to invoke the “Hour of Our Death,” to put the audience through the catharsis of confronting death (thus the frequent shots from the victim’s POV). By commenting upon the context of the horror film, and then explicitly tearing it down, Watkins does make strides toward erasing the barrier between artifice and reality. The spotlights of his movie set are constantly blinding us, turning the horrorshow in our direction – and making us ask why we seek out horror films in the first place (doubtless the film has inspired its share of walkouts, with fleeing audience members asking themselves that very question). It doesn’t provide pleasure or cheap thrills but intense discomfort and dread, and on that level, it succeeds. Watkins was not a genius, but for a film student on a drug binge, he managed to pull off something unique. I compared him to Haneke, as the film reminds me of Funny Games (1997, 2007) in the way it challenges the genre to which it belongs. Of course the more direct descendants of this film (and others, including Craven’s) are the so-called “torture porn” movies of the last ten years. Modern horror and its emphasis on extreme shocks and sadism have made Watkins’ nihilism seem mundane; horror fans of the Internet generation who seek this film out for sleazy thrills are already too jaded to find what they’re looking for. But I was surprised to find that I admired the film. I admire the way it commits completely and with a surfeit of gritty style, like a performance of Marat/Sade or Le Grand Guignol by college kids on acid. Love it or hate it, it’s authentic. Just not authentic snuff.