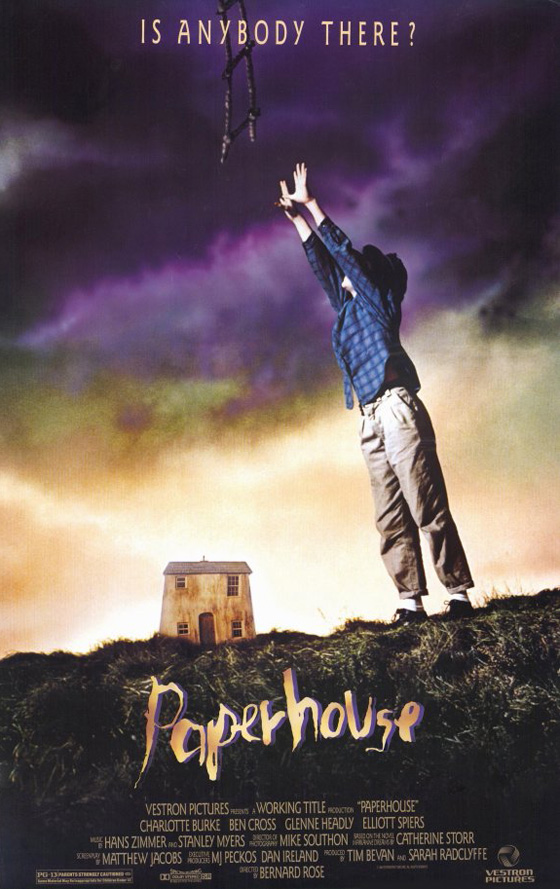

Every once in a long while someone mentions Paperhouse (1988), the big-screen debut of British director Bernard Rose (Candyman). There’s a kind of hushed reverence when the film is mentioned; it’s usually a bit like: “No one’s ever seen it, but there’s this wonderful little film called Paperhouse…” Or “The plot reminds me of this British film, it’s called Paperhouse, no one’s seen it but it’s pretty good, actually…” To the point that one grows suspicious: maybe everyone’s seen Paperhouse, only they all think that no one’s seen it, I’m not sure. But we know that’s not true. You’ve seen Paperhouse if you sought it out – any North American art-house release was cursory at best. For me, and I suspect it’s the case for a lot of people, it was the review by Roger Ebert that set me on the trail, until I found it at the video store sometime in the early 90’s. Ebert gave it four stars, and he wrote, “This is not a movie to be measured and weighed and plumbed, but to be surrendered to.” He praised the simplicity of the film, twice comparing it to Bergman, which is perhaps a bit too intimidating a comparison (unless you’re one of those adventurous souls who have discovered Bergman, and discovered that he’s not so intimidating after all). He wrote, “It’s like a Bergman film, in which the clarity is almost overwhelming, and we realize how muddled and cluttered most movies are.” He’s right, of course, about that and about the four stars. But I would assure the uninitiated that the film is not nearly as austere as all that. When I read the novels and comic books of Neil Gaiman, I’m reminded of Paperhouse. When I see a Stephen Moffat episode of Doctor Who, in which he takes a child’s nightmares and makes them real, I’m reminded of Paperhouse. (Actually, the 2006 episode “Fear Her,” written by Matthew Graham, is so close I believe Mr. Rose should be owed some money.) There are similar stories that predate the film (The Twilight Zone strikes close a few times) and after (one or two episodes of The X-Files, Joe Hill’s acclaimed comic book series Locke & Key), but what makes this film endure is the fact that it never takes its finger off the emotional pulse of its narrative. It’s a story about the frustrated, lively, and confused feelings of a girl on the cusp of puberty. Without being too showy about it, Rose completely engulfs you in her world – he draws you inside her head, so you can understand her rage and euphoria and sadness.

Anna (Charlotte Burke) explores her dreams, as Bernard Rose pays homage to the 1948 Andrew Wyeth painting "Christina's World."

Which is quite a trick, considering how off-putting stubborn young Anna (Charlotte Burke) is at the film’s outset. She prides herself on being the class rebel, sticking it to a bully and telling the teacher off, to the point that one of her classmates stands and applauds her. She faints outside the classroom, then turns it into a drama, taking advantage so she can go and enjoy her birthday at home. When her chain-smoking mother (Dirty Rotten Scoundrels‘ Glenne Headly, doing a decent British accent) discovers that she’s faking an illness to get out of school, she turns the car around. Anna sneaks off again, this time with a friend to an abandoned train station, where she passes out while playing hide-and-seek in a dark tunnel. A doctor (Gemma Jones, The Devils) finds she’s running a fever, but her recurring fainting spells indicate an illness worse than that. Anna doesn’t care. She doesn’t want to spend her time bedridden, but would rather be in front of the TV. Stuck in her bedroom, she loses herself in drawing, sketching out a house and a boy in the window. When she dreams, she visits the house exactly as she drew it – with, yes, a young boy in the window. The boy, named Marc (Elliott Spiers), is lonely and sad, and she thinks that’s because she drew him that way. He can’t walk, and she assumes it’s because she didn’t draw him legs. Each time she dreams, Marc is there waiting for her in her Paper House; and she slowly becomes convinced that he’s real – dreaming in the hospital, a patient her doctor described, one with muscular dystrophy and stuck in bed for a year.

The house that Anna built.

In trying to make some improvements to her dreamscape, she runs into trouble. Inspired by a photo she took of her (alcoholic and absent) father, she draws him into the picture as a means of inserting him into her dreams. But she has second thoughts; she’s worried she drew him to look like a madman. In a fit of anger and frustration, she crosses out his face – or, rather, his eyes – crosses out the boy’s window, crumples up the sheet of paper and tosses it in the trash bin. When she finally revisits her dreamworld – after a harrowing rescue from the garbage collectors – she finds it darker, visibly marred by her black markings. Her dream has become a nightmare. Her father approaches from the horizon, but as she drew him: deranged and blind. He holds a hammer in his hand and calls out to her, while she rushes to bar the door – which she never drew to have a lock. The radio on the wall – too large, like so many objects she drew to populate the house and provide comfort to Marc – glows like a jack-o’-lantern, and squeals out some unearthly, mumbling voice. Candles arranged on the floor, filling the room, suddenly extinguish, and a black shape stands in the darkness, a man without eyes.

The simulacrum of Anna's father (Ben Cross) carries her through the burning landscape.

It’s in moments like these that Paperhouse resembles a horror film – like a more inventive offshoot of the Nightmare on Elm Street series – and, however briefly, it works as a terrifically effective one. Rose worked for years with Jim Henson, and served as a production assistant on The Dark Crystal (1982). This, coupled with his experience creating videos for artists such as Roger Waters (contributing, with Nicolas Roeg and Gerald Scarfe, to his Pros and Cons of Hitch-Hiking live show), has given him a great sense of imaginative, evocative visual design that comes to the fore when the film suddenly kicks into thriller mode. But there’s more to Paperhouse, which escapes any genre pigeonholing. Specifically, there’s about twenty minutes more after the film’s climax, because Rose and screenwriter Matthew Jacobs, adapting Catherine Storr’s 1958 novel Marianne Dreams, know that you’re invested enough in Anna and Marc to want to know what happens to them. The extra celluloid is earned, because it follows through on the emotional arc of the story, bringing all the players – even her father, whose flaws inspired the nightmare doppelganger – to a cathartic conclusion that’s as messy and bittersweet as real life, without negating the story’s investment in the fantastic. (This is a movie that takes place in dreams, but it doesn’t settle for an it’s-all-a-dream ending.) Rose has continued directing films, but with a much lower profile following his justly-revered Candyman (1992), which remains the best film to be associated with Clive Barker’s name, and his Ken Russell-inspired Beethoven biopic, Immortal Beloved (1994). (Rose is a fan of Russell’s, and, just as in Russell’s films, classical music plays an important role in Paperhouse.) Paperhouse is available on DVD in the U.K. in a bare-bones release from Lionsgate (at least it’s anamorphic). A U.S. release of any kind would be welcome, and is certainly overdue.