Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) occupies an odd place in the Universal Monsters canon. It was released in a decade not typically associated with Universal horror’s height: the studio’s franchise had been run into the ground for years, having exhausted itself with cheap (but fun) B-outings like House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945), which crowded as many of its once-scary monsters as it could into efficient, mercenary productions. Ironically, what many point to as the death knell of the Universal Monsters is also regarded as a classic of its kind: Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), which put Bela Lugosi back in the cape as Dracula, initiated a new phase for the monster crew, now as straight men to Lou Costello’s comic hyperventilating. But this new series, which would also run itself dry (Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man, Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy, etc.), was not the swan song for the franchise. One last, completely original character would join up, and become every bit as iconic as Boris Karloff’s neck-bolts, Lugosi’s scowl, and the Wolf Man’s impeccable coiffure: the “Gill-Man.” Nonetheless, Creature from the Black Lagoon was the product of a natural evolution, independent of the Gothic horrors of the 30’s and early 40’s.

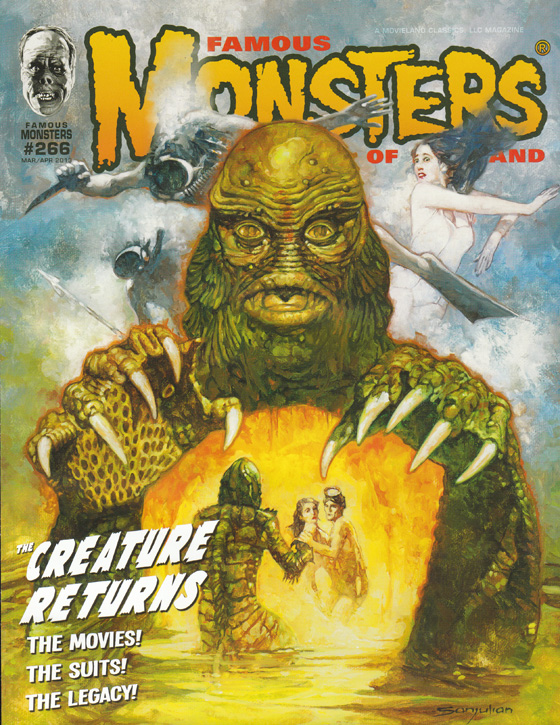

"Famous Monsters of Filmland" March/April 2013 cover by Sanjulian.

The film sprung from the imagination of William Alland, a former actor (having appeared in Welles’ Citizen Kane, The Lady from Shanghai, and Macbeth) who had taken to producing films. He reportedly got the idea from Gabriel Figueroa, a Mexican cinematographer (Los Olvidados) who told him the folktale of a half-fish, half-human monster living in the Amazon. Alland recalled the legend to his friend Jack Arnold, who had just directed the Alland production It Came from Outer Space (1953), a proto-Invasion of the Body Snatchers filmed in that trendy new process called 3-D. Their new, Amazon-set thriller would offer new opportunities to explore the 3-D process. Previously Arnold had sent a meteor-like spaceship crashing toward the audience. Now he’d use 3-D to provide depth, in his vast, ominous Black Lagoon. For genre fans, the 50’s are commonly associated with science fiction parables of paranoia and gloom (Rocketship X-M, When Worlds Collide, The Thing from Another World, Invaders from Mars, and so on), and the Atom Age’s monsters originate more frequently from the science of man rather than folklore or Gothic literature, including Arnold’s own Tarantula (1955). Creature was different. The Gill-Man was a monster who emerged from the Earth’s misty past, and it’s Man – and encroaching modernity – that threatens him. In spirit, he was much closer to Karloff’s Frankenstein monster, misunderstood and abused by those who seek to exploit him. So it’s easy and natural to group him with Universal’s monsters of the 30’s, and yet his origins in evolution, and his importance as a “missing link” (not to mention the technical sophistication of his innovative costume design), place him firmly in the more science-oriented, forward-thinking 50’s.

Mark Williams (Richard Denning), Kay Lawrence (Julie Adams), and David Reed (Richard Carlson) explore the dangerous depths of the Black Lagoon.

The film is lean and mean, free of unnecessary complications. After the fossilized hand of an apparently amphibian, humanoid creature is discovered in the Amazon, an American scientific expedition is launched, headed by Mark Williams (Richard Denning, Target Earth), and including the handsome David Reed (Richard Carlson, It Came from Outer Space) and his beautiful fiancé Kay Lawrence (Julie Adams, Bend of the River). While David and Kay radiate intelligence and scientific curiosity, Mark seems to fancy himself the Great White Hunter, and when they discover the Creature – and that he’s willing to protect his home with the savage swipes of his oversized claws – Mark is only too eager to go Ahab on this White Whale. I’ve seen this film twice in theaters, and Mark’s bullheadedness always gets some big laughs, particularly when Kay proposes that the Creature desires revenge; Mark: “I welcome it!” But much of the humor is intentional, particularly around the character of the jaded captain, Lucas (Nestor Paiva, of the Zorro TV series ), who, late in the film, happily vetoes Mark’s decision to stay in the Black Lagoon; the moment when he pulls a knife and presses it against Mark’s neck typically generates a cheer or two. Lucas is likable because he always has a smile on his face, no matter what the circumstances; you get the feeling that his boat, the Rita, may have been through worse.

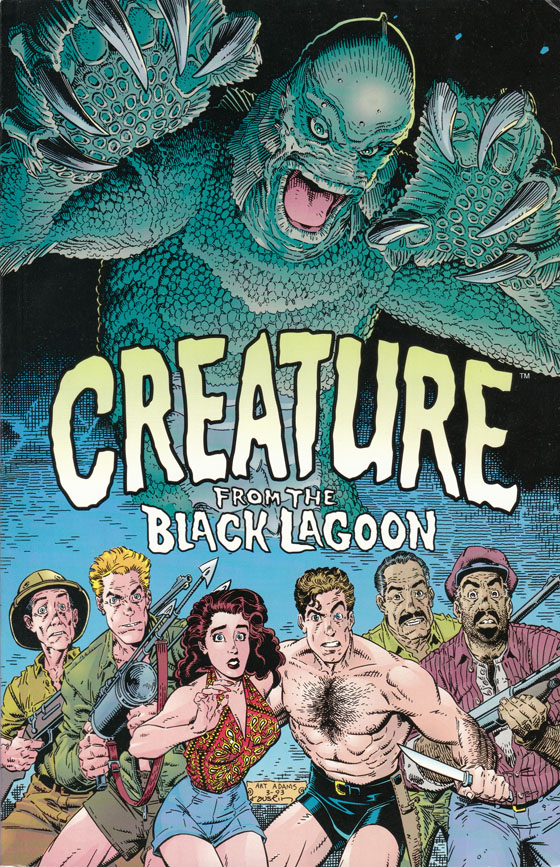

1993 Dark Horse Comics adaptation, with art by Art Adams and Terry Austin.

Time and again the Creature threatens the boat, maiming or drowning its crew members. The expedition tries to capture him, and when that fails, sets him on fire, and shoots at him with guns and harpoons. He just keeps coming back – and we can track the emotional progression of this expressionless monster. By the end of the film, he’s not only enraged at these invaders of his peaceful paradise, but cunning and plotting: he forms a barrier of wedged trees in the narrow channel leading out of the lagoon so that he can trap and kill the humans one by one. And yet his first encounter was one of gentle fascination. We first see the Creature in full while he’s spying on Kay, swimming above him in silhouette. Tentatively he joins her, swimming just below, his graceful movements mirroring hers. In the film’s most celebrated moment of poetic eroticism, he hesitantly reaches out toward her, daring himself to make contact. This moment of intimacy will soon be erased by the hostile reaction he receives from the crew of the Rita. He becomes a kind of assassin, striking at the most opportune moments, dwindling their numbers. In the climax of the film, which resembles a pulp Frazetta painting, the Creature kidnaps Kay and takes her to his secret cavern, shrouded in mist, and lays her upon an altar-like rock – he can now worship her female beauty with no interference. Of course, she’s rescued with blazing guns, and when we last see him, he’s floating, seemingly dead, in the waters of the lagoon. It’s an end just ambiguous enough to justify two further sequels: Revenge of the Creature (1956, also directed by Arnold and in 3-D) and The Creature Walks Among Us (1957).

The Gill-Man relaxes on set.

Apart from the subtle eroticism, the film also stands out for how it empathizes with its “monster” and, by extension, his desire to be left alone. The film is almost an environmentalist work – let the wilderness remain wild – though I’m not quite convinced, as some have argued, that scenes such as Kay dropping a cigarette into the water and the invaders polluting the lagoon with rotenone are satirical commentary on Arnold’s part. Yet the film straddles so many different ideas that it’s difficult to pigeonhole. The opening tells us that in the beginning God created the Heavens and the Earth, and then proceeds to explain Evolution so it can couch its Gill-Man in the domain of science rather than the supernatural. The film at first sides with David’s level-headed desire to keep the Creature alive, but eventually takes Mark’s position that it must be destroyed, once it becomes a survival-of-the-fittest situation (part of the film’s Darwinian theme). The film is both science fiction and horror. It’s simultaneously an homage to Universal’s past and an inextricable, vital part of its present: widescreen, 3-D, and scientific-minded. Even the score is a collage of different composers (including Henry Mancini), a patchwork quilt of film music that has somehow become iconic in and of itself. One of the aspects I love the most about this film is how perfect a metaphor it creates for the modern world at conflict with its past, divided cleanly by the Black Lagoon’s waterline. Above the water are the rational, evolved humans (who nonetheless bicker with one another and think in terms of capturing and killing); below is the murky, seemingly endless realm of the Creature, a dreamlike world which could be either our Id or our Collective Unconscious: familiar, ancient, primitive, archetypal. (There are even two Creatures, in similar but different suits: the “underwater Creature” is diver Ricou Browning, and the “surface Creature” is Ben Chapman.) Creature from the Black Lagoon can be whatever you want it to be, but it’s certainly more evocative and arresting than your average 50’s matinee movie.

Julie Adams signs my poster at the September 28th, 2013 screening and signing at Chicago's Patio Theater. Photo by Anne Luebke.

This past September, as the film nears its sixtieth anniversary, Chicago’s Patio Theater was host to a Creature from the Black Lagoon screening, featuring Julie Adams (accompanied by her son, and autobiography co-author, Mitchell Danton), who patiently, cheerfully signed autographs for a very long line of Midwestern fans, and participated in a post-film Q&A with author Foster Hirsch (Film Noir: The Dark Side of the Screen). With Hirsch she discussed the evolution of the Creature’s suit (the original, eel-like design, which was abandoned, looked ridiculous, in her opinion), the remarkable way Arnold shot Universal Studios’ backlot Black Lagoon to look like the most remote part of the Amazon, and speculated on the fate of her famous white one-piece swimsuit (she’s certain its latex has fallen to pieces these sixty years later). Of the erotic overtones of her swim with the Gill-Man, she states she was ignorant – though she opens up a bit more about this in the “Back to the Black Lagoon” documentary. The film was shown in 3-D, but of the unfortunate red/blue anaglyphic variety; it didn’t look terrible, but the original dual-projector stereoscopic presentation would have been far more impressive to witness during the film’s initial theatrical release. (The recent 3-D Blu-Ray is reportedly very well done, though I lack a 3-D TV set to appreciate it.) What was most gratifying was seeing how the film played so many decades on. The respectful audience was enthralled, and applauded appreciatively at the end. The Creature from the Black Lagoon has proven that he can still stand impervious to the march of time.