A few observations after watching Hammer’s The Curse of the Werewolf (1961) on the big screen.

#1 The Werewolf Weeps

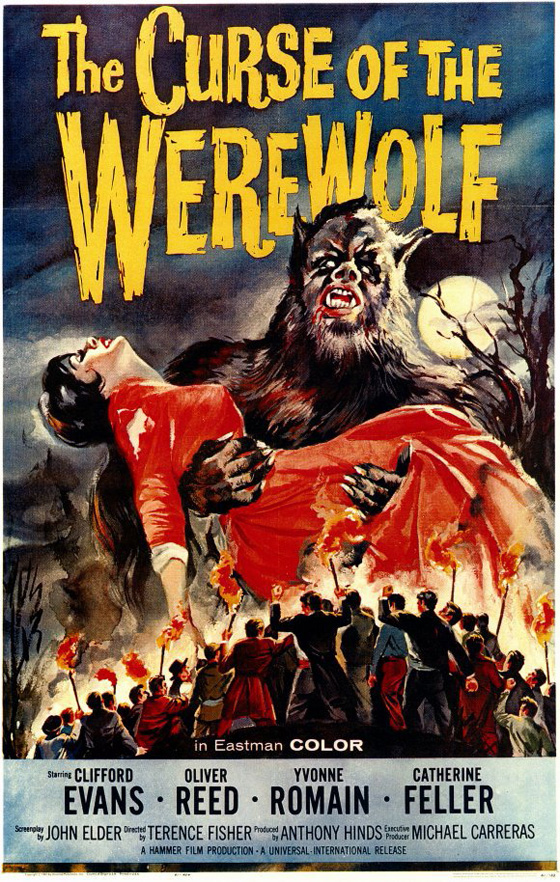

By 1961, Hammer had already placed their indelible stamp upon Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Mummy, updating the familiar tales with dashes of blood and sex. Terence Fisher, who helmed all those films, announces straightaway that The Curse of the Werewolf will be something different. While the terrific score by Benjamin Frankel (The Night of the Iguana) builds frenetically in the fashion of James Bernard’s work, Fisher zooms in close on the eyes of our monster, whose makeup will not be fully revealed until the film’s final scenes. We’re so close, in fact, that we can see the borders of Oliver Reed’s contact lenses, a fact that’s amplified on the big screen. And maybe it’s just the lenses that are causing his eyes to water. But the tears are a deliberate choice, linking this film with Universal’s The Wolf Man (1941) by emphasizing the tragedy of the Lawrence Talbot character, Leon Corledo (Reed). (Curse of the Werewolf was released on the 20th anniversary of the classic Lon Chaney, Jr. film, and was distributed by Universal International.) Corledo, like Talbot, is a good man shackled, through no fault of his own, to an evil beast within. He is forced to confront a horrible choice: either kill others every full moon, or kill himself. This is heavy stuff following Hammer’s previous monster-romps, and Fisher doesn’t hold back on unloading the story’s tragic weight.

Anthony Dawson and Josephine Llewellyn as the Marques and his new bride.

#2 Anti-Conventional Structure

Much has been made of the film’s extended prologue, and the fact that Reed doesn’t even appear until almost exactly halfway through the film; I’ve heard complaints and praise in equal measure. It’s certainly an example of Hammer’s confidence, or more specifically the confidence of Fisher and producer Anthony Hinds, who also wrote the film using his “John Elder” pseudonym. Audiences would flock to the latest Hammer Horror, so why not relax, take your time, and tell a ripping good yarn? To any who think that the film should get to its werewolf quicker, I’d point out a few things. For one, it would make for a more clichéd and conventional film. (It’s human instinct to judge a work against standards of the familiar, but it’s always worth pausing and noting that the unfamiliar is more interesting.) For another, the standard slasher-movie template is one Hinds smartly avoids, because that sort of thing gets repetitive and dull. But most of all, I love how the story unfolds like a fairy tale. A narrator tells us “Some two hundred years ago, a beggar came to the village of Santa Vera in search of charity.” He might as well say, “Once upon a time, there was a beggar.” Fairy tales and folklore often begin at the beginning of the beginning of the beginning. A modern-day reader perusing a book of Grimm’s Fairy Tales might be several pages into one before he realizes, “Oh, this is Sleeping Beauty; I recognize this.” Now imagine that you did not see the opening credits. You may be halfway through the film before you realize, Oh, this is a werewolf story. I recognize this. Frankly, I love that.

The mute jailer's daughter (Yvonne Romain), who cannot call out for help.

#3 Innocence Corrupted by Evil

The structure of the film, though not immediately obvious, becomes more poetic over multiple viewings. Fisher and Hinds are constantly “hammering” upon the same theme of the good and the innocent being corrupted by evil. The innocent beggar (Richard Wordsworth, The Quatermass Xperiment) is first humiliated at the court of the evil Marques (Anthony Dawson, Dr. No), then thrown into a dungeon, where he wastes away, and gradually becomes raving mad. The innocent jailer’s daughter (Yvonne Romain, Circus of Horrors) is raped by the now-evil beggar, who then dies. She takes out her vengeance upon the Marques by violently stabbing him. This history of corrupted innocence leaves its mark upon her bastard child, Leon. The holy water boils before the infant can be baptized in it; lightning flashes out the window and the devilish reflection of a church gargoyle is reflected in the waters. Later, the priest (John Gabriel, Corridors of Blood) will explain to Don Alfredo Corledo (Clifford Evans, SOS Pacific) that Leon has become a werewolf because the influence of the Devil will corrupt those souls who are left “weak,” and the infant Leon was left very weak indeed by his troubled heritage. (Incidentally, the audience I saw it with was surprised by the brutal fate of the jailer’s daughter. Her rape and subsequent revenge – tough stuff for 1961 – foreshadow the more extreme grindhouse films of the 70’s. Note also that the wounds left upon her chest by the beggar resemble the scratches of an animal; Hinds and Fisher originally intended to depict the beggar as becoming part-wolf before he attacks Romain.)

Don Alfredo Corledo (Clifford Evans) and his adopted son, the afflicted Leon (Justin Walters).

#4 Every Old Wives’ Tale is True

“You may think me superstitious, but I’ve seen a great deal more of the world than you have,” says Don Corledo’s servant, Teresa (Hira Talfrey, Witchfinder General). She tells him that the jailer’s daughter will give birth on Christmas day, and “for an unwanted child to be born then is an insult to Heaven, señor. That’s what I was taught. In the village where I come from, the girls stay away from the men in March and April, just in case.” Later, when Leon is old enough to begin changing shape and slaughtering the local goats, the villagers gather in the tavern and begin conjecturing about that wolf that’s on the prowl. (John Landis would later pay tribute to this scene in An American Werewolf in London.) Hammer mainstay Michael Ripper – for once, not playing the bartender – stumbles drunkenly about the tavern floor, mumbling that “Last night was the night of the full moon, and you know what that means!” People start to listen to these tales; they even give him more to drink. The tavernkeep, Pepe (Warren Mitchell, Hell is a City), finally melts down his wife’s silver crucifix to make a bullet. In one of Fisher’s most inspired moments, we see him level his gun at an off-screen wolf, and fire, before we cut to the young Leon (Justin Walters) back at his home – safe, but pulling feverishly at the bars his father placed in the bedroom window; Leon’s teeth are sharp and shining. We return to see Pepe gazing down at his prize: the goat-herder’s innocent dog. (This tragic moment deliberately foreshadows the shooting in the film’s final scene.)

The adult Leon (Oliver Reed), in the bed of Vera (Sheila Brennan), begins to succumb to the full moon.

#5 No Time, No Place

The Spanish village is an impressive set for the penny-pinching Hammer, and that’s because they couldn’t let it go to waste: it was built for a film about the Spanish Inquisition to be called The Inquisitor, but Columbia Pictures, worried they’d invoke the wrath of the Catholic Legion of Decency, withdrew their support for the project, leaving Hammer’s Michael Carreras to cancel the film and scramble for a new story. Hinds had already written a screenplay based on Guy Endore’s 1933 novel The Werewolf of Paris, and it was hastily rewritten to take place in Spain. But neither France nor Spain would explain Hammer’s typically domestic dialogue, such as Pepe’s declaration of “‘Ello! What’s this then?” when he discovers a slaughtered goat. A few scattered señors never quite convince of the setting, but this only adds to the Hammer charm – to a fan, this is pretty much what Transylvania sounds like, too. Potential disorientation abounds. The narrator’s opening declaration that his tale of the beggar and the Marques took place “two hundred years ago” doesn’t quite add up, since twenty minutes later he will introduce himself into the story (“It was here that I found her,” the narrator says, walking onscreen as Clifford Evans). Has Don Alfredo Corledo been alive for two hundred years? (Is he a vampire?) And how did Don Corledo know the story he’s been telling, since the surviving witness was a mute? (And even she would not have known the history of the beggar before she met him.) And how many days does a full moon last, anyway? Hammer made these movies very quickly. Though they distinguished themselves from the competition with an impressive veneer – fine acting, great costumes, terrific music, and color, widescreen cinematography – don’t push too hard or the façade might topple over.

Roy Ashton's werewolf makeup for Reed is a highlight of the film's spectacular climax.

#6 The Beast in Me

The romance between Reed’s Leon and the wealthy, privileged, and betrothed Cristina Fernando (Catherine Feller, Friends and Neighbours) forms the heart of the film’s second half. Yet there is an uncomfortable scene in which Reed accepts the advances of a seductive Spanish redhead (Sheila Brennan) in a nightclub-setting. In a feverish sweat from the full moon above, he follows her up to her bedroom for “a little lie-down.” We expect him to transform and kill her, and he does, but not before enjoying a lustful embrace. It’s the wolfishness coming out of him. And like Dracula, he takes a bite out of her, hungry for blood and leaving a red mark below her neck, before he devours his full meal. But in that moment when he kisses the girl, is he guilty of cheating on Cristina, or is he slave to the evil that was placed inside him before he was born? Regardless, he is overwhelmed with guilt and grief when he finds himself back in his childhood home, blood on his hands, and given the full truth of his “affliction” by Don Corledo and the priest. He knows he must die before he kills others, but at the description of his future – chained up until he’s delivered to a monastery (and perhaps kept in chains there) – he flees back to the village in fear and anger. We’re told that only his love of Cristina can save him, and he believes it and plans to elope; but the local authorities separate him from his true love, and lock him up (foolishly, they don’t believe the old wives’ tales, and think he’s just a common murderer). It’s a prison that’s not strong enough to hold him. Time and again it’s the image of prison bars that become the symbol of man’s cruelty to his fellow man, and what festers inside the cage will give loose to evil in the end. Surprisingly, Hammer never made a sequel, preferring to keep to its Draculas, Frankensteins, and Mummies instead. But with The Curse of the Werewolf they made a film worthy to stand beside Universal’s classic original – by staring its wolf-man in the eyes, unblinking.