This post is part of the Hammer Halloween Blogathon hosted by the Classic Film & TV Café. Go to www.classicfilmtvcafe.com to view the complete blogathon schedule.

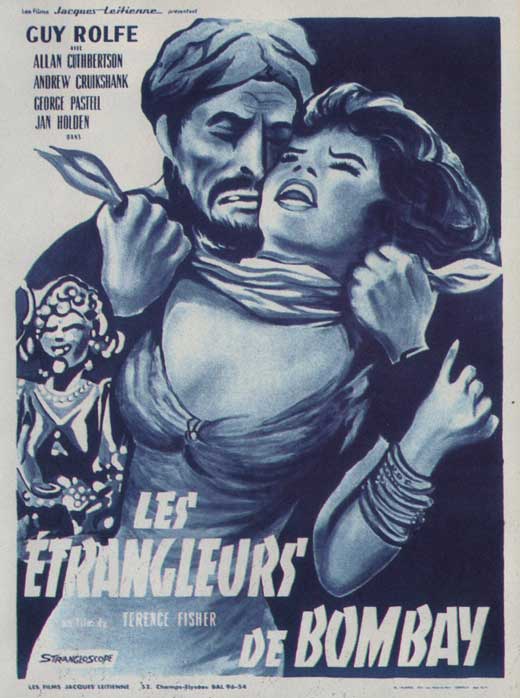

Terence Fisher was a busy man when he churned out The Stranglers of Bombay (1959) for Hammer Films. He had quickly become the go-to director for Hammer’s new wave of revisionist monster movies, having launched the Hammer horror cycle with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) only two years before, and quickly following with Dracula (aka Horror of Dracula, 1958) and The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958). The same year that would see the release of Stranglers also produced Fisher’s The Mummy, The Hound of the Baskervilles, and The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959); at least two of those are now considered classics of the studio’s output. Undoubtedly, this is Fisher’s peak period, though he would continue his association with the studio – in particular, with Peter Cushing’s Dr. Frankenstein – until his final film, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell, in 1974. So it’s understandable that The Stranglers of Bombay has a tendency to be overlooked: it’s not one of his more resonant films, neither Cushing nor Christopher Lee are in it, and it’s not part of one of Hammer’s popular horror series. Basically, this was just an assignment. But Fisher, at the top of his game, could not help but apply a layer of quality to the production. There is clear, concise storytelling in his compositions and edits; the film moves at a brisk pace, managing another low-budget Hammer epic in its 80 minutes. And though it is not strictly a horror film, Fisher achieves a nightmarish, almost claustrophobic effect. Regardless of how much of the film is historically accurate or British Colonialist fantasy, Fisher creates a world in which the Thuggee cult is all-pervasive, conspiring and inescapable; a world where even a crowded, well-armed caravan traveling through the jungle can be easily slaughtered in a single night.

Captain Henry Lewis (Guy Rolfe) questions the locals to find out why so many have gone missing.

The script, originally titled The Horror of Thuggee, was by the American playwright David Zelag Goodman, whose later screenwriting credits include Straw Dogs (with Sam Peckinpah, 1971), Logan’s Run (1976), and Eyes of Laura Mars (with John Carpenter, 1978). It went into production under the title The Stranglers of Bengal, and the marquee name would be Guy Rolfe, the prolific British actor who had appeared in Ivanhoe (1952) and Hammer’s Yesterday’s Enemy (1959); he would go on to play the villainous Mr. Sardonicus (1961) for William Castle, and take the late-career role of Toulon in the Puppet Master films of the 90’s. Here, as Captain Henry Lewis of the British East India Company, he plays the usual hero of these Colonialist adventures: righteous, possessed of wisdom, able to handle himself in a scuffle. He’d be a thoroughly uninteresting character if he weren’t set up against enemies on both sides: the Thug gangsters in the jungle (responsible, we learn, for upwards of a thousand missing persons a year), and the corrupt British officers around him. That latter point is important. What qualities we project upon Lewis are in part by contrast to his peers, who are portrayed as aloof and arrogant: Colonel Henderson (Andrew Cruickshank, El Cid) brings in the young, underqualified, but well-connected Captain Connaught-Smith (Allan Cuthbertson, Room at the Top) to investigate the disappearances, and the new appointee casually dismisses Lewis’s work on the case. It’s Lewis, of course, who bothers to go out among the locals to attempt to gain their confidence, instead of remaining behind his desk in a stuffy office; it’s Lewis who attempts to interact with the culture and the country surrounding them, though this sometimes involves hunting tigers with his white-hunter friend Sidney (Michael Nightingale). Ultimately, Lewis uncovers mass graves, but even this barely concerns Connaught-Smith, and it’s up to Lewis to single-handedly dismantle the cult, which has already infiltrated the East India offices in the guise of Thug spy Lieutenant Silver (Paul Stassino, Thunderball). Scenes of ritualistic torture and occult fetishism (humorously, there’s a 1930’s voodoo-movie quality to this Kali-worshiping cult) trade with surprisingly engrossing scenes of Lewis attempting to solve the mystery and convince those around him that there really is a sinister conspiracy at work.

Karim (Marie Devereux) watches while Lewis prepares for death by cobra.

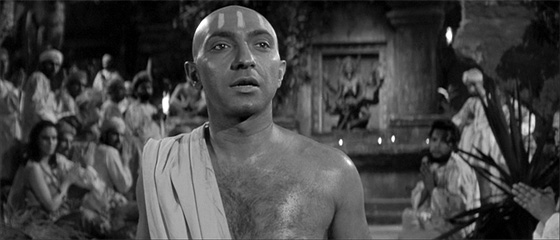

Look, this isn’t Pather Panchali. It’s pure British pulp and not to be taken seriously. Search elsewhere for political correctness: the spy Silver, of course, is half-Indian (gasp!), reinforcing an unfortunate suggestion that no one of Indian descent can be trusted, regardless of the fact that Lewis’s crusade is in part on behalf of the people – as indicated when he gives a horse to his servant Ram Das (Tutte Lemkow) so he can go in search of his missing brother. That screenwriter Goodman and the film’s producers probably knew more about India from Rudyard Kipling than anything else is evident in the presence of Lewis’s trusty mongoose, who saves him from a king cobra in a (real) confrontation that would definitely not pass muster with PETA. The Indian characters, as should be expected of a British film from 1959, are played by both Indian extras and non-Indian actors in makeup. Personally, I find Hammer’s The Terror of the Tongs (1961), with its eye-slanting makeup and cartoonish dialect, to be much more offensive. At least Stranglers has some evocative Indian subcontinent texture (of course, it’s shot at Bray and the city of Bombay is limited to a single walled-off set), and perhaps the fact that it’s filmed in black-and-white helps disguise some of the production’s limitations. Text at the end of the film links the story to history, and the quest of Sir William Henry Sleeman (1788-1856) to eliminate the Thugs (the fictionalized character of Lewis is apparently inspired by Sleeman). It should be noted there’s been some controversy in recent years over whether the Thugs were really prevalent in the 19th century – or if they, and Sleeman’s accomplishments, were just part of British Colonialist propaganda. The film’s depiction of the Thuggee as the “children of Kali” is correct, though placing them in a horror-movie context – not much different from the cults on display in The Witches (1966) or The Devil Rides Out (1968) – reminds that this is simply a Hammer genre movie. The climax, involving a high priest (George Pastell, who was an Egyptian in The Mummy), a crowd of cultists, a bonfire, and James Bernard’s pounding music, could be placed at the end of any Hammer horror entry.

A severed hand is delivered to the Lewis house.

Reservations duly noted, this is fun stuff. The story is told in a compelling way; as Lewis becomes increasingly isolated, and his friends are murdered or maimed – in one notable scene, his wife Mary (Jan Holden, The Camp on Blood Island) opens a package containing their servant’s severed hand – the tension builds. It’s easy to hate Connaught-Smith and root for Lewis, particularly as the odds get impossibly stacked against our hero, since it seems that nearly everyone is in on the conspiracy. (How do you recognize a Thug? They’re branded on the arm.) A highlight is the mass murder of the participants in a large caravan; the stranglers, with their “sacred cloth,” emerge suddenly out of the trees and descend upon the sleeping camp, wiping them out in seconds. Fisher adds some nice little touches, such as a transition near the opening of the film: two British officers abusively shout “Wake up then!” to an old Indian man standing beside a window. He pulls on a rope, and Fisher cuts inside the building, to the drapery to which the rope is attached, fanning the British elite inside: a moment that visually illustrates the divide between the Indian poor and their privileged rulers. The discussion that follows is between the Colonel and the displaced Patel (Calcutta-born Marne Maitland, excellent here), who can’t help but keep reminding the officers that his title now is strictly symbolic. (It will be revealed, of course, that he also is part of the Thuggee conspiracy. He’s secretly guiding an insurgency.) Much has been made of the film’s “sadistic” violence – a couple men are tortured, though it’s not graphically depicted by today’s standards; I find this frequent criticism exaggerated and ill-supported by a close review of the film, though I do love the line, “Slit their stomachs so their bodies do not swell!” In truth, The Stranglers of Bombay is an old-fashioned, very enjoyable adventure film with some horror elements, simply overshadowed by the Gothic achievements of Hammer’s, and Fisher’s, other films of the period. Plus, it has pin-up girl Marie Devereux in a small part (and smaller clothing) as a Kali worshiper. For a solid Saturday matinee, Hammer delivers – in “Strangloscope”!