Alfred Hitchcock was still a household name – nothing could ever change that. But by the early 1970’s, his status was somewhat tarnished following a pair of films that were less successfully received by both critics and audiences: Torn Curtain (1966; a film I personally enjoy) and Topaz (1969). The director, who had begun his career in silent film, was now in his seventies, in declining health, and seemed to be inextricably linked to Hollywood’s past; he hadn’t produced a genuine sensation since The Birds (1963). What would become his penultimate film, and his most successful in quite a while, had been bouncing about in his mind for years before he actually found the right property and the circumstance to film it. Disappointed with the experience of Torn Curtain, Hitch had decided his next film would be a return to small-scale, scrappy, lower-budgeted filmmaking. In other words, he wanted another happy and creatively liberating experience like Psycho (1960), and in fact the project he pursued would have had a similarly macabre theme, with a necrophiliac serial killer targeting a policewoman. The working title was, at various points, Frenzy. He prepared a treatment with Benn Levy, the screenwriter of Hitch’s Blackmail (1929) as well as James Whale’s classic Gothic The Old Dark House (1932). Alas, the project was scuppered by Universal, who suggested he adapt Leon Uris’s 1967 bestseller Topaz instead. Only when this project was complete did he again begin searching for a more personal project, eventually settling upon the 1966 novel Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square by Arthur La Bern, about a serial killer on the loose in London. Hitch was able to convince Universal that this new story, to which he was now attaching his favored title Frenzy, was superior to his former treatment and worthy of moving forward. Both Hitch and the studio realized there was something special about this film: it would mean that the director would be returning to his roots. He was returning to London.

Dick Blaney, played by Jon Finch.

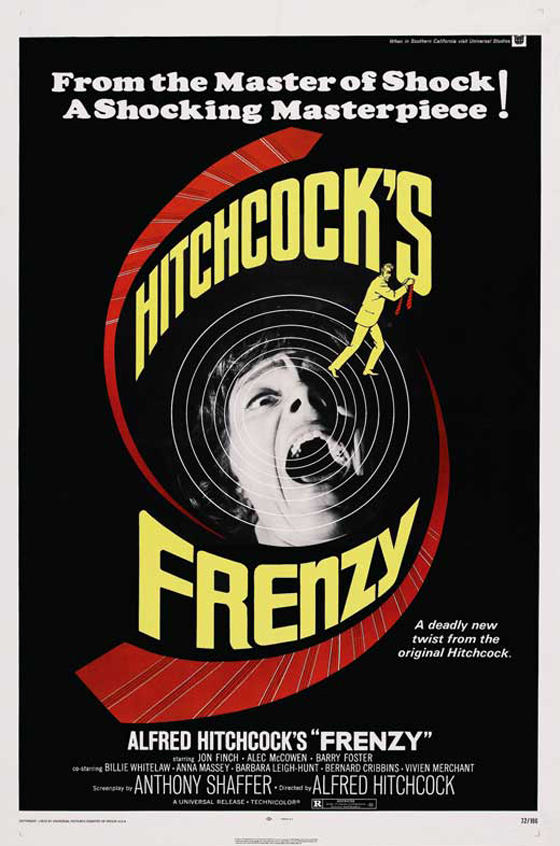

Ironically, Hitch was making a film for an American studio in England at a time when the British film industry was entering a slump that would last throughout the decade. Audiences for British films were shrinking, and British film companies increasingly relied upon whatever lucrative avenues they could find, which were primarily TV spinoffs and sex comedies. But Hitch would do his part, employing a British crew, a British screenwriter (Anthony Shaffer, author of the hit 1970 play Sleuth), and no Hollywood stars: when Frenzy was released in 1972, it was the name “Hitchcock” that towered above the title on the poster, an explicit acknowledgement that he was the true star of the film. Instead, the cast would be littered with faces that only British audiences might recognize, including Anna Massey (from Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom), Barry Foster (Battle of Britain), Alec McCowen (The Witches), Bernard Cribbins (The Railway Children), Billie Whitelaw (Gumshoe), and Jean Marsh (a TV actress who would later go on to high-profile films like Return to Oz and Willow). There’s no Grace Kelly here, as Hitch was casting for faces that looked like ordinary, unglamorous Londoners, contributing to the film’s gritty verisimilitude. Star Jon Finch, a theater actor, had been taking bit parts in Hammer horror films only a few years before, but his stock was rising, having just played the title role in Roman Polanski’s Macbeth (1971), one of the greatest – and grimmest – Shakespearean films ever made (and Finch is remarkable in it). Hitchcock, who preferred his actors just show up and deliver their lines with no fuss – and originally desired Michael Caine for the part – didn’t get along with the actor. According to Raymond Foery in his book Alfred Hitchcock’s Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece (2012), when Finch continued to suggest revisions to the dialogue, “Hitchcock quite ceremoniously halted the shooting until Anthony Shaffer could be summoned to the set for a consultation.”

Blaney and Babs (Anna Massey) on the run from the law.

Their rocky relationship is not necessarily detrimental to the film. Part of what makes Frenzy such an unusual Hitchcock film is that the “wrong man” in this Wrong Man plot is very unsympathetic. Finch’s Dick Blaney is a reckless alcoholic with too much pride for his own good. At the start of the film, he’s fired from a pub by the seedy Forsythe (Cribbins) on account of drinking on the job, and proceeds to gamble away the rest of his money with his friend Bob Rusk (Foster), who works at London’s Covent Garden Market. After he’s loaned some money by his patient ex-wife Brenda Blaney (Barbara Leigh-Hunt) – who works at a matrimonial agency that pairs up lovelorn singles – he splurges on a hotel excursion with his barmaid girlfriend Barbara “Babs” Milligan (Massey); never mind that he was sleeping at a Salvation Army shelter the night before. Blaney doesn’t pay much attention to the headlines – ANOTHER NECKTIE STRANGLING – until Brenda is raped and strangled in her office, the latest victim of the killer. The receptionist saw Blaney leaving the office and gives a description to the police. But the real culprit is best friend Rusk, who continues his psycho-sexual spree while Scotland Yard, led by Chief Inspector Oxford (McCowen), pursues the increasingly suspect Blaney.

Chief Inspector Oxford (Alec McCowen, center) arrests Blaney.

It’s a simple, even contrived, plot (adapted from a novel that would have gone forgotten were it not for this film), but a suitable template upon which the director could lavish his trademark detail, humor, and intricate, fastidiously-organized setpieces. Frenzy is another Hitchcock machine – and I don’t use the term unflatteringly – built to evoke the maximum amount of tension and discomfort in the audience before allowing cathartic release. Whatever you think of the film, Hitch’s enthusiasm is apparent, the 73-year-old rejuvenated by the opportunity to surprise, disturb, and thrill his audience in new ways. It’s the work of an auteur who’s finally allowed complete freedom again, and he doesn’t let it go to waste. But Frenzy is so designed to take the audience off-guard that it might take a second viewing to appreciate how carefully constructed the film really is. Shaffer’s plotting can seem meandering and sloppy the first time through. On a second viewing, one can see more clearly the months of work that went into the script, since every moment contributes to the whole. Frenzy, like Sleuth (which was released as a feature film the same year as Frenzy – and featured Hitch’s preferred star, Michael Caine), has the feel of a puzzle, despite the fact that we learn the identity of the killer very early on. This knowledge somehow makes the puzzle feel even more ingenious: it’s a three-way duel among the Wrong Man (Blaney), the Right Man (Rusk), and the Detective (Oxford). The audience is invited to engage in the game and guess how it will resolve itself, how these three players will finally come together, while simultaneously feeling the floor drop out from under them as Hitch pushes his own personal boundaries of shock. The director here enjoyed one of his rare happy collaborations with a writer, having found someone as obsessed with playing the audience as he was. (Regrettably, though he intended to work with Shaffer again on Family Plot, negotiations fell through.)

Hitchcock gets his obligatory cameo out of the way at the front of the film. He wanted the audience's attention on the plot.

Without completely spoiling the ending, I think the way in which the film concludes is telling: our three players are finally standing in the same room, a single, witty line of dialogue is delivered, and the credits roll. Note that there is no actual denouement, a la the final scene of Psycho. There’s no dead weight, and even though the audience has a right to wonder what precisely will happen to Blaney now, it’s something of a relief that we’re spared the details. (Blaney is an unsympathetic character who gains our sympathies only because he’s not guilty of the crime. So Hitch and Shaffer don’t even bother to tell us what ultimately becomes of him!) A similar excision happens during a courtroom scene two-thirds of the way through the film. Hitch and Shaffer dodge the familiar, dull proceedings, which we’ve seen a hundred times in a hundred other movies; instead, we sit outside with the officer watching the door, and when it swings shut, we can’t hear the droning judge’s sentence. We don’t need to. There will be no stock scenes in a Hitchcock film.

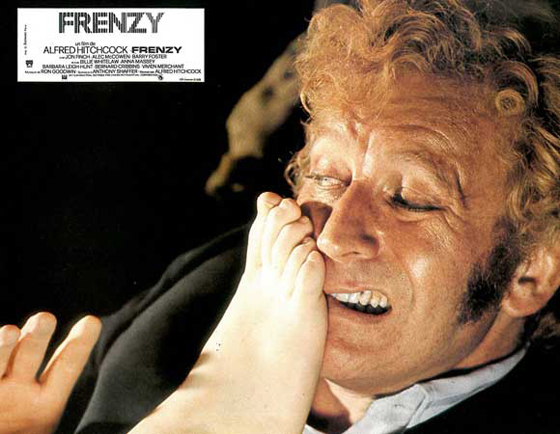

Rusk (Barry Foster) strangles Brenda Blaney in "Frenzy"'s most notorious setpiece.

So it’s an efficient and exceptionally clever script that holds up to subsequent viewings. What the audience does take away on that first viewing is that this is the work of a Hitchcock of the 1970’s, a Hitchcock with an adult rating: R in the U.S., X in the U.K. (note that practically every horror film got an X too; the connotations for the rating were quite different in Hitch’s home country). He no longer needed to merely imply rape, as he does in Marnie (1964). He was permitted to show it, and so, for the first time since the one-two of Psycho and The Birds, he could truly shock his jaded audience once more. 1972 was, after all, the year of Deep Throat, so there was no need for him to make the same type of films he was making a decade before. Thus you get the rape of Brenda Blaney, which is disturbing, graphic, and almost unbearable in its intensity. Note that just as with the shower scene of Psycho, it is edited with images like a collage (though not cut as fast, because the intent is that the scene feel queasy and prolonged). I don’t have to watch the film to recall those images: Brenda’s brassiere being pulled down, her flailing legs, her arm extended into the air, the tie tightening around her throat, her eyes dashing back and forth while she loses oxygen. And, of course, Shaffer’s increasingly abstract dialogue, as the bestial Rusk is reduced to repeating “Lovely…lovely…lovely.” Ron Goodwin’s score is silent during this scene, which only makes it more uncomfortable, claustrophobic, and real. Hitchcock has been accused of misogyny – for this film, and in general – but it is important to realize that in a suspense film, the audience only needs to be shocked once. They will remember the shock and dread it occurring again – which is why the next murder occurs off-screen. It happens to a character that the audience has grown very close to, and so Hitchcock only needs to show the door close while Rusk delivers a familiar line, the same he said to Brenda before he killed her. Then, in what might be the film’s most bravura moment, Hitch’s camera slips back from the landing, down the stairs, and out the front door. Amazingly, his camera is in synch with the audience’s grieving.

A lobby card depicting Rusk's nighttime journey to recover his missing pin.

Another notable setpiece is Rusk’s desperate attempt to recover his trademark pin from a body smuggled into a sack of potatoes in the back of a moving truck. The scene, and its placement and intent, directly parallels Norman Bates’ effort to dispose of Marion Crane’s car (and body) midway through Psycho. Famously, the scene generates tension on behalf of the killer: will the car sink into the swamp, or will Norman be stuck with incriminating evidence? There, Hitchcock proved that he could create suspense out of nearly anything, even making the audience empathize with a man who’s covering up the murder of the person we’d thought was the main character (this moment seems even more perverse once the truth about Norman Bates is revealed). Frenzy‘s nighttime truck-ride similarly attempts to put the audience in Rusk’s shoes. If the scene suffers by comparison, that’s because (a) the other film is Psycho, for crying out loud, and (b) Anthony Perkins’ awkward, self-effacing Norman Bates is a considerably more likable character – his real crimes be damned – than Rusk’s brutal rapist. (Note that at the beginning of the scene that will end in Brenda’s rape, she’s uneasy about Rusk as soon as he enters the office. He’s just an unpleasant, disconcerting kind of guy. On the other hand, the couldn’t-harm-a-fly Norman comes across as charming to Marion Crane, and by proxy the audience.) If Frenzy can’t pull off with Rusk what Psycho can with Norman, that’s OK, because Hitch and Shaffer decide to play the scene for a slightly different angle: black comedy. And this is very black comedy, considering that the morbid slapstick – a stiff foot kicks into Rusk’s face while he scrambles to find his pin; rigor mortis stiffens the fingers that are clutching it, so he has to break them one by one – is centered on the corpse of a person that the audience cared about, and was made to care about (which I emphasize, because we’re being manipulated by Hitch and Shaffer), before being killed by this very man. Still, the scene comes off, and it’s one of the most memorable in the film. To invoke “catharsis” again: being reminded that we’re partaking in another of Alfred Hitchcock’s macabre games helps us get over the trauma of the film’s more pitch-black moments. By this point, we want to laugh, and an audience familiar with Hitch’s sense of humor – all those Alfred Hitchcock Presents introductions – can plug into his black humor vibe more easily.

Chief Inspector Oxford is served another ambitious meal by his wife (Vivien Merchant).

More gentle comic relief comes in the form of Chief Inspector Oxford’s all-too-believable domestic life, as we see him endure one ambitious meal after another served by his wife (Vivien Merchant, Alfie). Her culinary creations appear to be largely inedible, and the couple is endearing not just because Oxford tries to endure his wife’s suppers without complaint (though, should she leave the room…), but also because she acknowledges his dislike of the meals by casually noting that she’s sure he’d like some steak and potatoes instead. She’s educating his palate, it seems. And she’s also weighing in on the case, an opinion he values, which makes me wonder if this is how Hitch saw his relationship with his wife, Alma Lucy Reville. It was Alma who at one time received co-authorship credit on many of his scripts, Alma who continued to approve each of his projects and offered suggestions to improve them. He valued her opinion more than anyone’s; I’m not exactly sure how he felt of her cooking. These scenes are deliberately placed to break the tension, to allow the audience to breathe and to smile. And I think Hitch relished the opportunity to showcase warm, simple British domesticity, as it had been so many years since he’d filmed in England. The opening shot of the film, a long helicopter swoop over the Thames, places an unusually formal heraldic banner at the corner of the screen declaring “The City of London,” which I’d imagine generated some applause when it premiered there. But his London was one of the past; as Foery notes in his book, “[Shaffer’s] only stated quibbles regarding the Frenzy scenario had to do with what he took to be Hitchcock’s odd insistence on dialogue that seemed quaint by contemporary standards.” Hitch’s London, gritty and bleak as it might be, could be said to exist outside of time. It’s the London of popular imagination. In an early scene of the film, Hitch deliberately sets his tale against the expectations of that backdrop when one gentleman comments to another: “We haven’t had a good, juicy series of sex murders since [John] Christie. And they’re so good for the tourist trade. Foreigners somehow expect the squares of London to be fog-wreathed, full of hansom cabs, and littered with ripped whores, don’t you think?” With Frenzy, Hitchcock would not only announce that he was still the master of suspense – he would also give cinematic tourists the London they wanted.

Midnight Only is a proud participant in the Hitchcock Halloween blogathon presented by Backlots.net. Please visit Backlots.net for a complete list of Hitchcock Halloween essays.