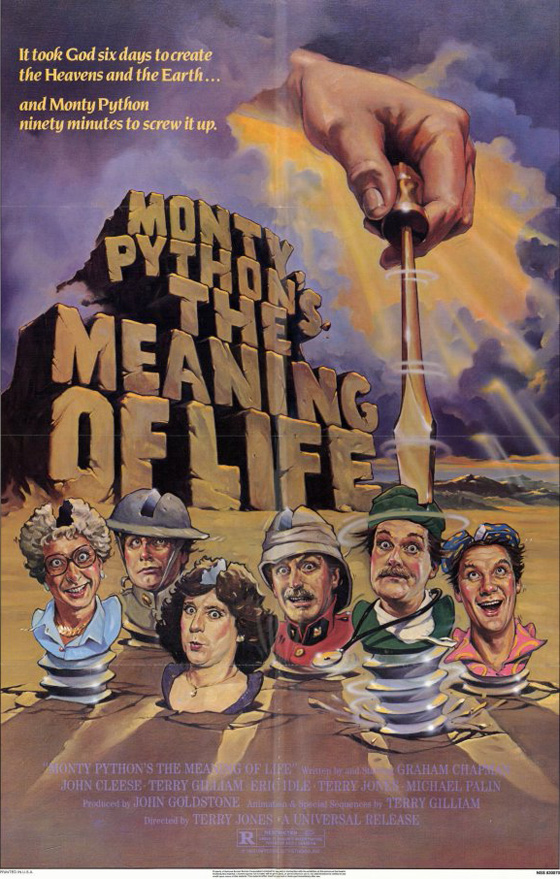

In the official pressbook for Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983), the last of the Monty Python films and the formal end of the group’s creative output, Graham Chapman described the film’s story thusly: “We start just prior to fertilization, I suppose, and then move on through the fertilization of the ovum until we reach, more or less, the fetus, and then birth shortly followed by death. Well, there’s an intervening stage called life, but then we’re on to the more important bits again – death, and the consequences of it.” Eric Idle wrote a poem which adorned the pressbook (and which he read in a bit filmed for the 2003 DVD); it began, “There’s everything in this movie, everything that fits/From the meaning of life in the Universe, to girls with great big tits.” For the record, Idle’s description is more accurate than Chapman’s. The Meaning of Life would prove to be an appropriately spectacular capper to the career of Monty Python, but it also suffered a particularly painful birth (even more awkward than the one which begins the film), and in subsequent years, most of the Pythons have expressed dissatisfaction with it. Fans tend to prefer Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) or Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), but I recall that in my high school years The Meaning of Life was one of those you-have-to-see-this movies thanks to its sheer outrageousness. Mr. Creosote and his wafer-thin mint! Every Sperm is Sacred! And, yes, those “girls with great big tits,” chasing Chapman over a cliff in the film’s shortest sketch, which surely helped make this a must-see among teenage boys. The Pythons have a right to grumble about the film’s shortcomings; they’re the authors, after all, and in their eyes the film didn’t meet the standards they’d set with their previous work. But Life of Brian was magic: the anarchic, occasionally juvenile, frequently razor-sharp Python humor leveled at the big, fat, and utterly taboo target of organized religion. That was an achievement that was difficult to top. And if Meaning of Life isn’t as good as the other Python films, surely it’s funnier, more insightful, and more chock-full of visual delights than most cinematic comedies of its day, or since.

Roman Catholic Michael Palin teaches his army of children that "Every Sperm is Sacred" in the eyes of God.

As Michael Palin recalls in The Pythons Autobiography, “We wrote a huge amount of material that never got used. It was much more of an uphill struggle getting The Meaning of Life going. It’s very, very hard to know where you go after Life of Brian. In fact, I remember us thinking that – where do we go next? And I think the seven ages of man – birth, life, death – that idea, the really big one, was seen as the only way you could cap Life of Brian. We never really considered going back and doing a smaller, gentler movie.” He notes that one of the suggested titles was “Monty Python’s World War III.” The pressbook offers a few other working titles: “Sex and Violence” (not coincidentally, the title of an early episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus) and “Monty Python’s Fish Movie.” Hoping that lightning would strike twice, the Pythons attempted to recreate their tremendously productive 1978 Barbados sabbatical which resulted in the Life of Brian script; this time, they went to Jamaica for two weeks to hammer out a screenplay. It was a logical move: increasingly, the Pythons had been taken in different directions by their burgeoning careers. John Cleese was, for the time, content to turn out humorous corporate training videos; he was considering even retiring from films altogether. Palin had made The Missionary (1982) for Handmade Films. Chapman was working on Yellowbeard (1983). Terry Jones had hosted a BBC show called Paperbacks and written a scholarly book, Chaucer’s Knight. Idle had made The Rutles (1978) with his friends at Saturday Night Live, and wrote a play called Pass the Butler (1981). Gilliam had made Jabberwocky (1977) and Time Bandits (1981), and was already thinking about his next project, which would become his greatest work: Brazil (1985). It’s hard to keep a band together. So in Jamaica, the stakes were high: either produce a work as a team, or dissolve Monty Python for good. After two days of nothing being achieved, frustrations mounting, Cleese and Palin were ready to abandon the project and just enjoy a nice vacation without the pressure of work. It would mean the end of Monty Python, surely (though Palin did float the suggestion that they could turn their written material into a TV series). But overnight Jones had come up with a structure for the film: their material could be anyone’s life story, from birth to death. (Later, Idle would lament that they didn’t push the idea just a little bit further, and have the sketches form the life of one central character – say, their usual leading man, Chapman – passing through the Seven Ages of Man.) A skeleton of a shape in place, work resumed.

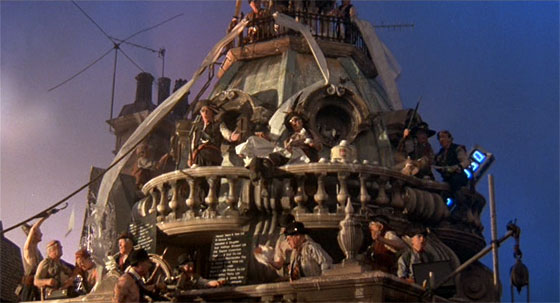

Terry Gilliam's short film, "The Crimson Permanent Assurance."

There was no argument that Jones should be the director, having instituted a happy working atmosphere on Life of Brian; Gilliam was frustrated in his previous attempts to wrangle the stubborn Pythons on Holy Grail, and disliked sharing the director’s chair as he did with Jones on that film. Instead, Gilliam would get free reign on a short segment intended to be inserted halfway through the film, “The Crimson Permanent Assurance,” described in the published screenplay as “A Tale of Piracy on the High Seas of Finance.” With minimal oversight, the budget quickly ballooned on Gilliam’s mini-epic, as did the running time. Jones recalled in Monty Python Speaks!, “We originally thought he was doing a five-minute animation, it was only when we heard that Terry wanted another million dollars or whatever it was, we suddenly realized it was a whole different feature going on! We kept going to his studio next door, and he had these huge sets compared to what we had.” We shouldn’t complain, because we don’t “balance the books” (to borrow a line from Idle’s accompanying sea-ditty); we just get to enjoy the end result: a sixteen-minute comic fantasy which resembles one of his Flying Circus cartoons brought wondrously to life, and clearly the testing grounds for what would become Brazil (the image of an office building with billowing sails weighing anchor and breaking free from the city, its elderly employees dressed up with everyday office supplies to resemble buccaneers, is clearly the work of the man who directed Sam Lowry’s paperwork-themed dreams). After test screenings, it was clear that “The Crimson Permanent Assurance” couldn’t remain anchored to the center of the film; the motley film broke free to become the short that precedes The Meaning of Life. At the appropriate moment, it then crashes into the main feature and temporarily hijacks it, until that usual polite Pythonesque apology is heard in voice-over, the “Permanent Assurance” miniature is unceremoniously flattened, and The Meaning of Life resumes.

Jones as Mr. Creosote.

The best-known segments in the film admittedly trade on shock value. The most famous involves gallons and gallons of fake vomit. It is, of course, the “Mr. Creosote” sketch, in which the character – for which “morbidly obese” is an insufficient description – vomits so frequently that a single bucket beside his dinner table quickly proves insufficient. As a piece of comedy, it’s fascinating, because on the one hand Cleese’s performance as a French waiter sells the bit: he’s almost profoundly patient, impeccably polite, and, just before the bill can be presented, rebellious and devious in the way that only those suffering in the service industry can be (when Creosote is finally full, Cleese pushes an after-dinner mint: “it’s only wahffer thin…”). Cleese has defended the sketch as a treatise on greed. But on the other hand, when I watched this for the umpteenth time last night, I found myself laughing aloud at the comic timing of the vomit. Yes, we can all admit it: the vomit is funny too. When the bucket is removed so another one can be fetched, and Jones, as Creosote, launches another stream straight onto the carpet, it’s hilarious. Partly because we can see the horrified reactions of the patrons in the background. Partly because the scatological can be very, very funny when used just right. Earlier in the film, Cleese is teaching a classroom full of students (and conspicuously middle-aged Pythons) about sex with a live demonstration. As he takes the missionary position with his wife (The Rocky Horror Picture Show‘s Patricia Quinn), he grows increasingly irritated with his bored, distracted audience. I particularly enjoy Palin’s schoolboy whose ocarina is confiscated by Cleese. He’s asked to bring it to the front, and Palin awkwardly walks right up to the naked Cleese and Quinn, proffering the ocarina. “[Put it] on the table!” Cleese scolds. There’s plenty of shock value in “Every Sperm is Sacred,” but all at the service of completely decimating the Catholic Church’s stance on birth control. It seems impossible to watch that musical number and still believe there’s any logic to the official Papal stance on coitus. But, yes, you’re also laughing because Palin is delivering graphic dialogue to a cast of children: “Oh, they’ve done some wonderful things in their time. They’ve preserved the might and majesty, even mystery of the Church of Rome, the sanctity of the sacrament and the indivisible oneness of the Trinity. But if they’d let me wear one of those little rubber things on the end of my cock, we wouldn’t be in the mess we are now.” (Not to worry: Palin actually said “sock” before the kids, and they dubbed in “cock” later.)

Idle and Palin, who may or may not have stolen an army officer's leg, try to justify why they're wearing a tiger costume (in Africa).

The apparent consensus about The Meaning of Life is that it’s an uneven film: it has good bits in it, everyone seems to say, but it’s not that successful on the whole. I’ll politely disagree. The birth-to-death arc works, and as a sketch film – always a difficult thing to pull off – it holds together quite favorably when compared to others in the genre (it’s much more cohesive, clever, and satisfying, I would argue, than Mel Brooks’ similar History of the World: Part I). The film could be tightened, and some of the bits dropped: Palin’s “Marching Up and Down the Square” drill sergeant sketch falls flat, though at least it’s short. The film needs more of the stream-of-consciousness linking material we got in Flying Circus, though some of this can be blamed by last-minute changes: the winning “Protestant Couple” ends awkwardly only because a linking sketch was dropped at the last minute, for example (kind of a shame – the deleted piece, “The Adventures of Martin Luther,” is an exceptionally silly bit that’s more in the vein of History of the World: Part I, but boasts some very funny performances by Jones, Chapman, and Palin). Maybe Gilliam should have been persuaded to do more animation to tie everything together. The Meaning of Life contains the last of his work in this medium, but the opening title sequence – set to Idle’s hilarious theme song, sung in a disgusted French accent – ranks among the best of his Python animation. Jones has also matured as a filmmaker, having cut his teeth on the previous Python films. It would be wrong to state that Gilliam’s short outclasses the rest of the film. Although Jones’ technique has always been to spotlight the comedy – to make sure the bits work and the actors get laughs, regardless of how it looks – there are enough striking visuals (and visual gags) to ensure that the big-budget, cartoon-brought-to-life quality of “The Crimson Permanent Assurance” is maintained throughout. Think of the grubby domestic kitchen falling away to reveal the vast universe and “The Galaxy Song” (after Idle emerges from a refrigerator, for some reason). Think of the sprawling, Oliver!-style musical number of “Every Sperm is Sacred,” which eventually brings in a fire-eater and a Chinese dragon. Think of the bed that emerges organically from the wall of Cleese’s classroom, or all the kitsch sights contained in Chapman’s “Christmas in Heaven” number. It’s a visually dense movie, rewarding multiple viewings with its attention to every funny little detail.

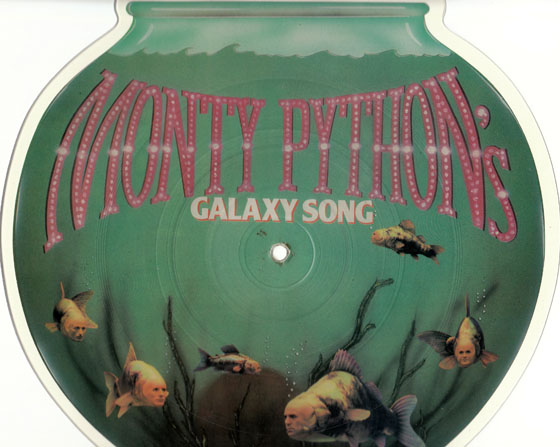

Fishbowl-shaped promotional single for the film.

One of the things I’ve always loved about Python is their attention to every aspect of their brand, at least while they were still active (that standard has loosened since, and now you can get Python anything). This is the group that once released the world’s first three-sided comedy record. For Holy Grail, they issued a soundtrack album that boasted lots of new comedy sketches written and performed especially for the album, and the tie-in book contained different drafts of the screenplay, allowing the fan to see how the film developed. The Meaning of Life only saw a slight flagging of enthusiasm on the part of the Pythons: the soundtrack was mostly just dialogue from the film, with only a tiny bit of new linking material thrown in. The tie-in book was just the screenplay, although well-designed and featuring deleted material, including the aforementioned “Martin Luther” sketch. But the single, “The Galaxy Song/Every Sperm is Sacred,” offered another fine Python collectible in that it was the first ever vinyl single shaped like a fish bowl. (Perhaps the best by-product came in 1998, in the form of 7th Level’s enjoyable Meaning of Life PC game, made with the involvement of all the surviving Pythons. For a while, playing the latest 7th Level Python game was the closest thing to getting a new Monty Python movie.) As for the film, it won the Grand Jury Prize at the 1983 Cannes Film Festival. The release date was brought in and the film reached audiences sooner than expected; upon its arrival, Newsweek called it the troupe’s “best movie.” It seemed that Monty Python could still shock, but people had grown to expect that, and welcomed it. Rather than inspiring the kind of picketing and boycotting that Life of Brian did, the Pythons were becoming an institution. No wonder they called it quits – and Chapman’s death in 1989 closed that door permanently, barring the occasional incomplete reunion. It’s all for the best. The Meaning of Life, whatever its faults, is a fitting end for Monty Python, returning the sextet to their roots as an anarchic sketch-comedy troupe; as though confident this would be their swan song, the eerily appropriate final image of the film is the opening credits of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, playing on a television set that floats slowly off into outer space. The Pythons were often called the Beatles of comedy, and, like the Beatles, they were allowed to write their own ending; this is essentially the Python equivalent of Abbey Road, the gang coming back together in opposition to those tidal forces that were pulling them apart, all for one last send-off. For that, I treasure this film.

NOTE: On The Meaning of Life‘s 30th anniversary, a Blu-Ray has been released which ports over most of the DVD’s special features, as well as a new hour-long Python reunion. Sadly missing from the previous release is the option to watch the film with the deleted segments re-inserted; the scenes are viewable as a supplement, but not without Jones’ commentary running over them. (In other words, someone at Universal screwed up. Don’t throw your old DVD away.)