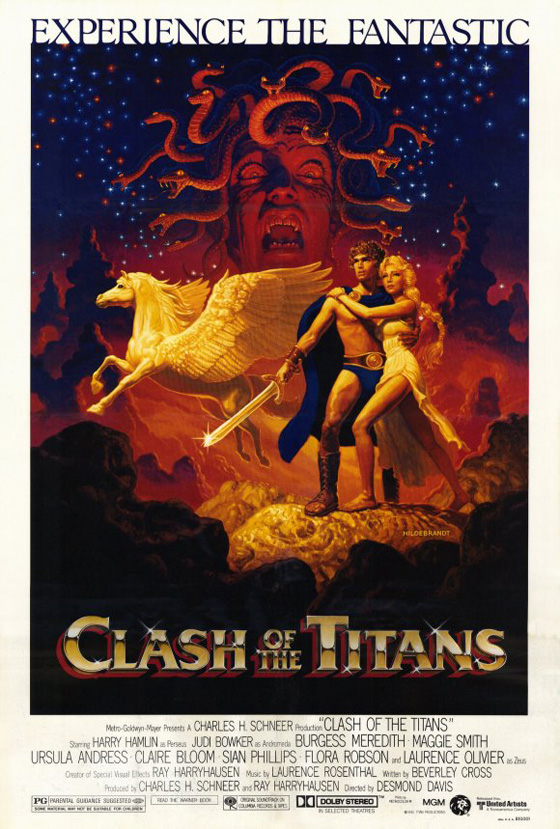

So yesterday I went to Thor: The Dark World (2013), and – probably because I had just re-watched 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) that morning, I was particularly struck by how far special effects have come, how casually sophisticated they are. Hardly a scene in the film goes by without some kind of CGI effect. In one moment, we catch a glimpse into some kind of Asgardian museum where it appears that a galaxy is suspended in the boughs of a tree. It’s not commented upon; it’s just there. It’s a fine moment of surrealism, or at least Marvel-brand psychedelia in the vein of Jack Kirby’s Thor comics. Of course, since this was a Marvel film, I was obliged to sit through the ending credits for the Easter egg at the end. The seemingly endless scrawl listed one special effects company after another. Fast-forward to later in the evening, when I decided to revisit the original Clash of the Titans (1981). The credits were much shorter, because most of the work – apart from some assistance by Steven Archer and Jim Danforth – was by one man, Ray Harryhausen. Sure, his creations don’t look as “realistic” as the monsters and cosmic environs of Thor: The Dark World. But his stop-motion miniatures all moved at the guidance of his hands, and that makes a difference: this is a spectacle with fingerprints.

Perseus (Harry Hamlin) enters the Underworld to confront Medusa.

The appeal of the original, analog Clash of the Titans – and I make this distinction because the 2010 remake feels like a bland video game, one that you’re watching someone else play – relies a lot upon your affinity for Harryhausen, as well as how old you were when the film came out. I was five. Harryhausen fans of an older generation probably have mixed-to-negative feelings about the film, since it simply can’t touch the brilliance and magic of his seminal works, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Those films are much better, but they also belong to the childhood of the so-called “monster kids.” To the next generation, Clash of the Titans – along with Star Wars (1977) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) – helped form the basis of their blossoming imaginations. At least, they did for me. And while Clash of the Titans‘ weaknesses seem more evident the more time passes, I have an inescapable nostalgia for this movie, partly because I grew up with it – I’m pretty sure this is where I saw a naked woman for the first time – and partly because it became Harryhausen’s swan song. Stop-motion would stick around for just a little while longer, but in more subtle forms, such as go motion, to further the illusion of reality. It was even briefly considered for Jurassic Park (1993), until Spielberg became convinced that computer effects had come far enough to deliver his dinosaurs. In middle school, and long before Jurassic Park, my Latin teacher showed Clash of the Titans to the class, and as soon as the first of Harryhausen’s creations – the giant winged vulture – appeared on the TV, the students started to laugh. I wanted to stand on my desk and lecture them on who Ray Harryhausen was and the depths of his achievement. In retrospect, it’s probably a good thing I just shrunk down into my seat instead.

Judi Bowker as Princess Andromeda.

With the benefit of hindsight, this is a fitting end to Harryhausen’s string of films with producer and longtime partner Charles H. Schneer. The film has an all-star cast, some attractive location shooting, and – most importantly – lots of monsters; it was a return to form after stumbling slightly with the low-budget Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977), a film that had the misfortune to be released the same year as Star Wars, and which Harryhausen fans frequently, casually refer to as the master’s weakest (for the record, I enjoy Eye of the Tiger, and as I’m writing this, the gorgeous poster for the film is staring down at me). The credits proudly boast the presence of Sir Laurence Olivier as Zeus, and as far as I’m concerned, his is the definitive interpretation, though I also have a fondness for the more earthy, low-key Niall MacGinnis in Jason and the Argonauts. Besides Olivier, the film has a post-Rocky Burgess Meredith as the poet Ammon, Ursula Andress as Aphrodite (though present, it seems, just to sell the film – she hardly gets any lines), and a host of esteemed British actors including Maggie Smith – Professor McGonagall herself – as the vengeful Thetis and Claire Bloom (The Haunting) as Hera. Olivier spends most of the film sitting at a throne with sparkling blue laser-lights beaming from behind his head. He projects the regal quality necessary, and only falters in a strange scene where he speaks to his son Perseus (a pre-L.A. Law Harry Hamlin) through a magic shield: he delivers his lines as though heavily sedated. Of the gods and goddesses, the real star is Smith, whose Thetis is perennially annoyed at Zeus for the favoritism he shows his bastard son, and the punishment he visits upon her child, Calibos (Neil McCarthy, Where Eagles Dare): he gives him horns, scaly green skin, and a lizard’s tail. Smith captures the righteous anger of a goddess quite well as she invokes a curse upon the city of Joppa through the image of her stone idol – a scene that truly feels like Greek mythology brought to life. Although Hamlin’s performance is only adequate, he’s given plenty of solid support with Burgess Meredith as his mentor, an appealing Tim Pigott-Smith (Quantum of Solace) as his soldier friend Thallo, and the stunningly beautiful Judi Bowker (Brother Sun, Sister Moon) as his predestined lover, the Princess Andromeda.

One of Ray Harryhausen's creations: Dioskilos, the two-headed guardian of Medusa's lair.

What attracts me to the worlds of Harryhausen is that around every corner there’s a lost temple or some fearsome creature. The highlight, and the raison d’être, of the film is Perseus’ journey to the Underworld and his subsequent duel with Medusa. Even among Titans detractors, no one argues that the Medusa sequence belongs in every Harryhausen highlight reel. But I love everything that leads up to it, including the River Styx ferryman Charon, a skeleton dressed in black who appears out of the fog, extending his bony hand to request the toll. They should at least descend down some kind of pit to reach the Underworld, not simply walk there, but it seems nonetheless significant that it’s that easy. In a Harryhausen film, wonders await at the end of a long journey, you simply have to go. After a battle with a two-headed dog, Dioskilos (kind of a demi-Cerberus), Perseus and his men enter a dark temple of pillars lit only by torchlight. Harryhausen’s design of Medusa is creative: not only does she have snakes in her hair (which move, unlike Hammer’s The Gorgon), but her lower body is nothing but a snake’s tail, including a rattlesnake’s rattle. Since Perseus can’t look at her directly, he can only hear the hiss of her snakes and the shake of her rattle, before she nocks an arrow and lets fly. When one of his men is caught in Medusa’s gaze, her eyes glow green, and he turns to stone. As a demonstration of Harryhausen’s craft, the sequence is superb: he captures the flickering torchlight upon her scaly features, while he moves every serpent, as well as her roaming eyes and the arms that pull her body across the temple floor.

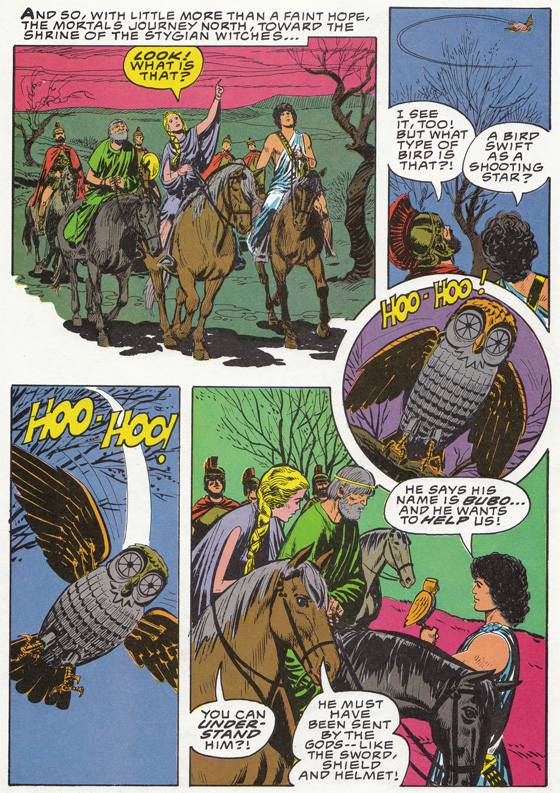

A page from the Golden Press softcover graphic novel, depicting the introduction of Bubo the owl. Art by Dan Spiegel.

Other notable creations in the film include the winged horse Pegasus, Bubo the mechanical owl, and the villain Calibos. Like Pegasus, Calibos (inspired, in a nice touch, by Caliban of The Tempest) is stop-motion only in long-distance shots, and the cuts between stop-motion and live action are always obvious and never seamless (but who cares?). The advantage of stop-motion is that Harryhausen can get Calibos’ lizard-tail moving with expression as he battles Perseus in the swamp. Perseus’ capture of Pegasus is memorable not just for the beautiful animation of the horse flapping its giant feathered wings through the evening sky, but also the way it tries to “buck” its rider – a nice example of Harryhausen’s subtle humor and empathy for his creatures. A battle with giant scorpions, which grow from Medusa’s blood, evokes his earlier giant-animal movie Mysterious Island (1961), and even if the climactic appearance of the Kraken is more iconic than impressive, at least it has four arms! As for Bubo, he’s always been a divisive character. Though Harryhausen often protested it, there’s obviously an R2-D2 influence (Perseus is the only one who can understand his electronic bloops and bleeps); and in the remake, his cameo is little more than an excuse to insult the poor little fella. I always liked him, though, again, I was five when this came out. As with all Harryhausen films, the Blu-Ray treatment has a tendency to spotlight the seams of every effect; many of the optical effects are embarrassing as a result (to name one example, Poseidon floating beside the Kraken’s undersea lair looks pretty horrible). But look past the rougher moments and there’s plenty to enjoy. Advances in technology may have pressed Harryhausen into an early retirement, but with Clash of the Titans he provided a satisfying send-off to the era of stop-motion fantasy. Much of it shows its age, but Harryhausen’s charm is preserved just fine.