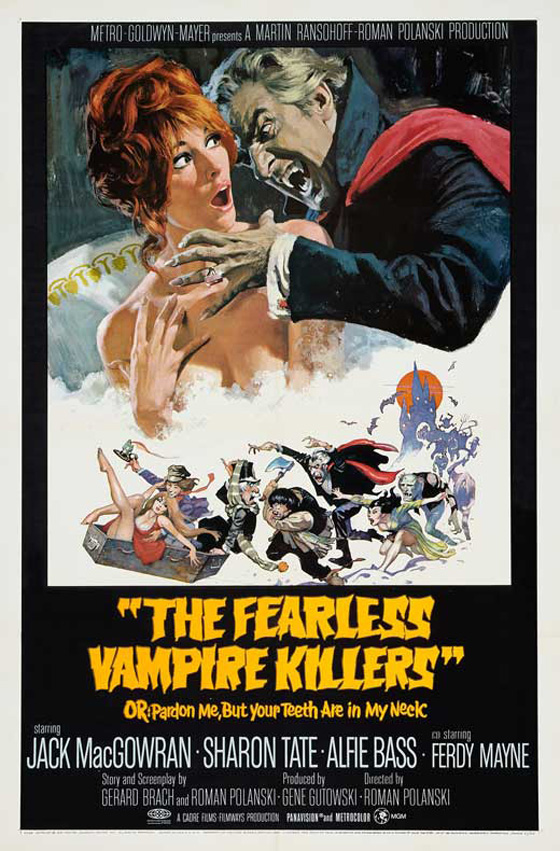

Roman Polanski had, over the course of four years and a trilogy of taut psychodramas, Knife in the Water (1962), Repulsion (1965), and Cul-de-sac (1966), established himself as one of the most exciting young directors to emerge from Europe – but despite his proven versatility and quick transition from Polish to English-language films, he hadn’t yet cracked Hollywood. When Polanski and screenwriter Gérard Brach, his collaborator on Repulsion and Cul-de-sac, conceived the idea of a Hammer horror spoof to be called Dance of the Vampires, they attracted the attention of an American producer, Martin Ransohoff (The Americanization of Emily). Polanski was excited at the idea of making a film for Ransohoff and his production company Filmways, which had a distribution deal in place with MGM. It seemed to be a gateway to Hollywood. Ransohoff saw Cul-de-sac and said he loved it, securing the American distribution rights. Polanski, won over, placed his trust in the man. He agreed to give Ransohoff and Filmways final cut of Dance of the Vampires in the States, as long as he could retain final cut in all other territories. He might as well have made a pact with Dance of the Vampires‘ Count von Krolock; Ransohoff passed the film into the hands of MGM’s Supervising Editor Margaret Booth, who would suck the film bloodless. Released in 1967, the film was renamed The Fearless Vampire Killers, or: Pardon Me, But Your Teeth Are in My Neck. Tacked on before the opening credits is a crudely-made, two-minute-long cartoon that doesn’t match the tone of the film (even if it does use the waltz music from the film’s climax). As Glenn Erickson has outlined in his DVD Savant column, the film was shortened by about twelve minutes and Professor Abronsius (Jack MacGowran, Cul-de-sac, Doctor Zhivago) was redubbed with a more intelligible but cartoonish voice. In his 1984 autobiography, Roman, Polanski was still fuming – at Filmways and his producer, not MGM. “He was a compulsive butcher of other people’s work. ‘Let him finish the picture,’ he used to tell his associates, ‘then I’ll do my number.’ It was hardly surprising that no directors lasted long with Filmways, even when – like Norman Jewison, J. Lee Thompson, and Arthur Hiller – they had multiple-film contracts.”

Roman Polanski and Jack MacGowran as the vampire hunters, assistant Alfred and Professor Abronsius.

Yet flash-forward decades later and that American cut is hard to find. Polanski’s version has become the only one that’s widely available on home video, even if it’s under the Fearless Vampire Killers title, the most harmless of the alterations. Naturally his is the most satisfying viewing experience. What MGM failed to realize is that the film is so distinct and unique that no one is going to like it more with a few scenes excised and a short cartoon and some wacky dubbing added; for those not on board, it’s still a very strange and very dark “comedy.” And those who count themselves as fans, myself included, love it as much for the chilly Eastern European atmosphere and bleak tone as much as the absurdist humor. About his and Brach’s screenplay, Polanski wrote, “Our basic aim was to parody the genre in every way possible while making a picture that would, at the same time, be witty, elegant, and visually pleasing. The script was a joy to write; Gérard and I spent much of the time in fits of laughter.” But The Pink Panther this is not. There’s blood and a pervasive feeling of impending doom. The film’s heroes, Professor Abronsius and his assistant Alfred (Polanski), are so hapless and incompetent that they don’t stand a chance against the wicked Count von Krolock (Ferdy Mayne, The Vampire Lovers), his son Herbert (Iain Quarrier, Cul-de-sac, Wonderwall), and their undead minions. Because of these two – the only two standing in the way of the vampire plague spreading beyond Transylvania – all humanity is doomed. We know this because the narrator tells us so.

Alfred interrupts Sarah (Sharon Tate) during her bath.

Shot around a ski resort in Valgardena in the province of South Tyrol, far up in the mountains of northern Italy, Fearless Vampire Killers boasts an authentic snowed-in look for its small Transylvanian village. The chief attraction in this little village is an inn where the residents gather to drink, their frostbitten faces puffy and red from long walks through the snow. In the month of December, Abronsius and Alfred arrive through the snowy slopes with sleigh bells ringing, but their sleigh is assaulted by a pack of biting wolves, which Alfred beats at impotently with his umbrella. The wolves carry it off with them as a prize. (Note how the final scene in the film echoes this one, only it’s a slipper Alfred loses to the snowy road, and something within the sleigh is baring teeth at him.) Abronsius, whose chief weapon against vampires is that he doesn’t have enough blood in him to fill a cup, is already frozen stiff, and apparently dead, until they’re brought into the inn and warmed up. Polanski symbolizes the warmth of the inn with two images: their bare feet stuck into buckets of steaming water, and the bountiful cleavage of Magda (Fiona Lewis, Lisztomania), the blonde maid who scrubs their feet. (When he stirs, Abronsius is looking in the opposite direction, at the ceiling, and immediately points out the garlic strung up like mistletoe.) The amorous, innocent Alfred also finds inviting the beautiful, freckle-faced, red-headed Sarah (Sharon Tate, Valley of the Dolls, Eye of the Devil), daughter of the innkeeper Shagal (Alfie Bass, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum). He and Abronsius first lay eyes on her by accident, when Shagal opens the door to the bath, revealing Sarah dressed only in soap bubbles.

Sarah watches from above as Alfred builds a snowman.

This blend of realistic, highly detailed earthiness and overt sensuality are typical of Polanski’s style, though in Fearless Vampire Killers the sensual and human are a dwindling commodity – one prized by both the half-dead villagers and the undead vampires who threaten them from the nearby castle. Just as Shagal lusts after Magda, sneaking out of his wife’s bed every night to visit the maid’s bedroom, the pale and gaunt von Krolock lusts for Sarah’s youthful health, stealing her straight out of her bath – in one of the film’s most poetic nightmare images, the snow drifting down through the open windowpane above her just before the vampire descends in his fluttering cape – and eventually displaying her before his vampire brethren like some choice cut of meat. In the castle ballroom, the bright reds of her hair and flamboyant dress are vividly contrasted with the washed-out 18th-century wardrobe and gray faces of the vampires. She is life, and it’s Alfred who’s racing to preserve what’s left of it. Professor Abronsius could care less; he’s continually dismissive of the idea of rescue: when Alfred asks for whom the woodcarving hunchback Koukol (Terry Downes) is building a coffin, Abronsius shrugs as he surmises that it could be for Sarah or either one of them. Alfred, meanwhile, finds himself locked in the hungry gaze of von Krolock’s “gentle, sensitive” son Herbert. “Did you provoke him?” asks Abronsius after Herbert chases Alfred throughout the castle. “No, he got excited all on his own!” Alfred protests, choking on the garlic that he’s pulled out of his pocket.

Count von Krolock (Ferdy Mayne) greets the vampire hunters.

If the jokes about Herbert’s sexuality seem a little politically incorrect by today’s standards, the staging is so brilliant and funny that they do not feel dated or insulting. The emphasis is on elegant farce, not camp. Herbert’s attempted seduction of Alfred (“Shall we let an angel pass?”) and his subsequent pursuit through the castle’s Escher-esque hallways – while Herbert waits patiently, Alfred runs a full circuit, down and up stairs, until he’s back where he’d begun, standing side-by-side with the vampire – provide some of the film’s most effective moments of pure comedy. One could also argue that the film’s Jewish characterizations of Shagal and his wife are borderline problematic (“Oy, oy, oy,” they constantly moan), but, although not every gag lands, the Jewish Polanski was drawing an affectionate portrait, just as he affectionately modeled his Abronsius after Albert Einstein. As F. X. Feeney writes in his 2006 book Roman Polanski, “a joke about Jewish vampires and their indifference to crosses would only occur to one for whom being Jewish in a world of Christian mythologies is a matter of life and death. Professor Abronsius and young Alfred notice the inn is encrusted with garlic. ‘Is there a castle in the district?’ the professor asks, and his hosts gasp, refusing to answer. To not only bow to a tyrant but deny his existence is a ghoulish paradox so human one cannot help but feel hints of life under the Nazis intruding, like a ghostly chill.” This too is felt in Shagal’s constantly addressing von Krolock as “Your Excellency,” bowing to authority, but also pleading to it when Sarah is stolen. “Your Excellency! Give me back my daughter!” he screams, clutching to the ceiling window out of which she was stolen. There is something heartbreaking about his marching off into the snow with garlic and to his wife’s tearful goodbyes, setting out for the castle and his certain doom. This isn’t just a spoof of vampire movies. Polanski, who had spent his youth on the run from Nazis, had internalized this tragic tone that constantly threatens to undercut the slapstick of Fearless Vampire Killers.

Count von Krolock offers Sarah as a gift to his vampire followers.

The film is imperfect; it can be lumpy, and would justify some editing, albeit not of the sort MGM provided. It really takes off about 45 minutes in. Once we arrive at the castle (a very memorable set, built at the MGM studios in England), and Abronsius and Alfred try to get on with the business of vampire killing, the blend of comedy and horror are in perfect balance. A perilous, vertigo-inducing trip to the Count’s crypt leads to the professor getting stuck in the window, and a terrified Alfred holding his stake in the wrong direction. The actual “dance of the vampires” – which seems at least partly inspired by Hammer’s Kiss of the Vampire (1963) – demonstrates how sophisticated a filmmaker the young Polanski had already become. He was given to tour-de-force moments of pure cinema; think of the long take in Cul-de-sac in which a plane flies overhead right on cue with the performance of the actors. Here, our vampire killers don disguises to infiltrate the grand ball and attempt to steal Sarah out of the clutches of von Krolock, and Polanski uses the choreography of the dance – set to a harpsichord waltz by his favored composer, Krzysztof Komeda – to allow our three players to swing in and out of view as the dancers move about the floor, brief snatches of sentences hastily exchanged among them, doused with unearned optimism. (My favorite line goes to Alfred, as he tells Sarah: “It is I. Life has a meaning once more.”) The impeccable farce climaxes as the three find themselves accidentally standing before a giant mirror, immediately foiling their subterfuge. A few scenes later, the hunchback attempts to pursue the fugitives by using a coffin as a sled, leading to more painstakingly precise choreography. The scene required the coffin to slide down the hill and miss the fleeing sleigh by inches. “On the fourth take I overdid it,” Polanski wrote. “Hans [Möllinger, the stuntman] shot across our front, shaving the shaft of the sleigh with his head and only narrowly missing the horses’ hooves. That, needless to say, was the take I used.”

A flaw in the vampire killers' plan: there's a mirror in the ballroom.

The film was a success everywhere but the U.S., where it had been sliced and mangled. Polanski, who had greatly enjoyed the shooting (he would glide across the set on skis), now found the film’s treatment by Filmways and MGM depressing. He’d learned his first lesson of Hollywood: “The whole atmosphere was symptomatic of the situation that arises when a major studio invests heavily in a picture and then loses interest in it. Hollywood is like that: a spoiled brat that screams for possession of a toy and then tosses it out of the baby buggy.” A phone call from Robert Evans at Paramount led to events that would lift his spirits. Evans strongly believed that Polanski was the only man to be behind the camera for this property of William Castle’s called Rosemary’s Baby. Soon Polanski would be flying to the States, having been handed the keys to the kingdom at last, with an opportunity to demonstrate his talent on a much larger scale. But Fearless Vampire Killers would prove to be a significant moment in his life nonetheless. Originally he had intended to feature Jill St. John in the role of Sarah, and when the studio insisted he hire Sharon Tate, he was skeptical. She looked too American. Not Jewish enough. And he’d have to put a wig on her to give her the red hair he wanted. But he quickly realized he’d found his Sarah, and it was on set, and on film, that they fell in love. Come 1968, the year of his breakthrough adaptation of Rosemary’s Baby, they would be married.