When we think of Russian cinema, we think of Sergei Eisenstein, Andrei Tarkovsky, Dziga Vertov. But we can learn just as much about Russia by looking at a genre that held great popularity among its people for decades: the fairy tale film. Vassilisa the Beautiful (Vasilisa prekrasnaya, 1939), directed by Alexander Rou, was a seminal work in this category, a large-scale, gorgeously composed film of special-effects escapism. While World War II was erupting across Europe, Russian audiences flocked to a film that returned them to a folkloric past, a medieval Russia of superstitious peasants, dark forests, friendly bears, three-headed dragons, and the cunning witch Baba Yaga. The film hits upon almost every trope of the Russian fairy tale with little to no attempts at modernization. (Only a scene set in a vast temple of tall, dominating arches, its bare floor painted with concentric, hypnotic black rings, visually recalls, ironically, 1920’s German expressionist films – you’d be forgiven for thinking it was directed by Fritz Lang.) It’s fine that Vassilisa the Beautiful is only loosely adapted from its titular source – much of it is borrowed from another fairy tale, “The Frog Tsarevna” aka “The Frog Princess” – because it plays like a Greatest Hits collection of fairy tales, and with a zippy running time and images ripped from a children’s book, it sets a high bar for Russian fantasy films to come.

An example of the film's beautiful peasant-Russia production design.

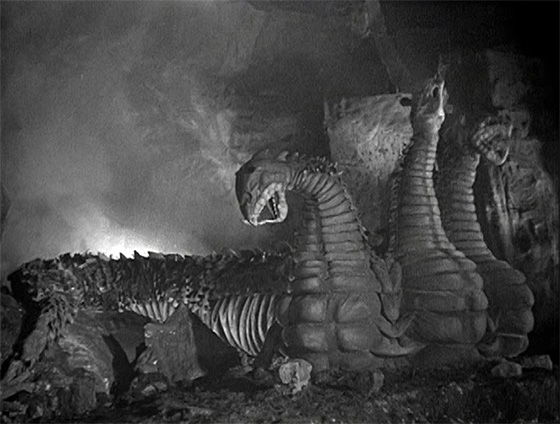

Many Russian fairy tales take as their protagonist an innocent fool named Ivan or Ivanushka, and he often has some wicked or selfish older brothers. Here our Ivanushka (Sergei Stolyarov) is the gentlest and simplest of three brothers who work on the farmstead of their wise father (Georgiy Millyar). When Father grows impatient with the irresponsibility of his sons, he orders them to each launch an arrow into the air and marry the woman who carries it back. In this manner, brothers Agafon and Anton each find a rather unpleasant wife, one haughty and the other a glutton. Ivanushka’s arrow lands in a pond, sticking in a lilypad which rises to the surface and produces a rather large frog. He commits himself to marrying it. That night, the two wives observe the frog removing its skin and revealing a pretty young woman, Vassilisa (a charmingly plump V. Sorogozhskaya). Jealous of her beauty, and thinking the frog skin granted it to her, the two wives of Agafon and Anton fight over the skin and accidentally rip it in two, destroying it and breaking the curse that had been cast on Vassilisa. We learn that the three-headed dragon Gorynych had turned Vassilisa into a frog when she refused to marry him, and not long after she’s restored, Baba Yaga spirits her off to marry her to the dragon. Ivanushka is told by his father that the only weapon which can slay Gorynych is a sword hidden in a well and behind a locked door. From a blacksmith, Ivanushka learns that the key to the door is inside a golden egg, inside a duck, inside a crystal chest, hanging from a pine tree.

Ivanushka enters the black forest.

As in the language of children’s literature, everything Ivanushka is told is true; we are told of these fantastic things, and then, eventually, we see them, all realized with beautiful production design by Vladimir Yegorov (Baba Yaga’s treehouse, though it doesn’t have chicken legs, is still a sight to behold). There are hallucinatory optical effects, matte paintings that are part Arthur Rackham, part Hieronymus Bosch, and bizarre monsters, including Baba Yaga’s owl with glowing eyes, a spider with a pulsating abdomen that catches Ivanushka in its web and asks him riddles, and Gorynych himself, a dragon that breathes wind, fire, and water. (When Ivanushka severs this last head, water gushes forth instead of blood.) In the woods, Ivanushka wrestles with a bear, which in some shots is a real bear, and in others a man in a suit; when the bear later cuddles with her cubs, it is a man in a suit cuddling with real cubs – one wonders what those cubs thought. After our hero gets free of the spider in the well, he swings his Slaying Sword against the blackness, which breaks apart (it almost looks like he’s broken the film), revealing a bright chamber beyond, and a mirror; in the reflection he sees himself in a suit of armor, and then, suddenly, he is wearing it. A horse arrives to carry him away, and he somehow knows its name. This is fairy tale fantasy with a heavy dose of surrealism. It is evidence that this Russian genre had discovered a cinematic syntax for dreaming.