“You are seven years old. You are a man. Bury your first toy and your mother’s picture.”

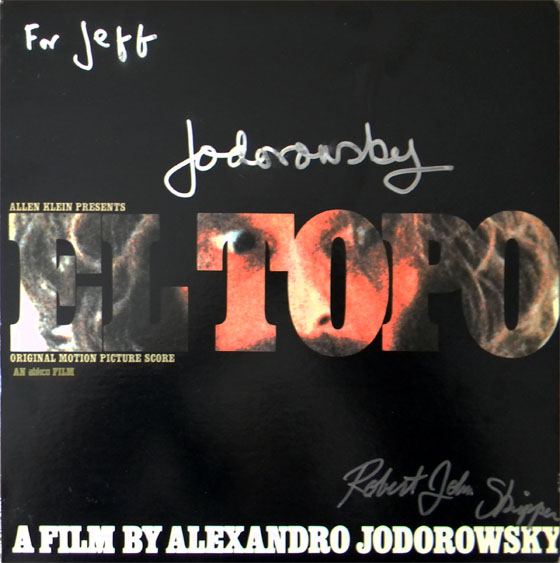

A gunslinger clad from head to toe in black, carrying a black umbrella, gives his naked young son a teddy bear and a framed black-and-white photo. The boy digs with his hands in the desert sand. They ride off on a horse against a blue sky, the gunslinger holding his umbrella aloft, while a melancholy theme plays on the soundtrack. So begins the legendary El Topo (1970), the surreal Mexican Western from the Chilean-born Alejandro Jodorowsky, and the film that helped launch the midnight movie phenomenon. It is a movie in which midnight screenings were only logical. Transgressive, violent, sexual, and stream-of-consciousness, the film was a natural heir to the late-night underground film scene and the boundary-pushing films of Andy Warhol and Kenneth Anger. But while Warhol and Anger – and many of their lesser-known contemporaries – embraced classic Hollywood while seeking to subvert it, Jodorowsky’s influences were genuinely foreign. He seemed to have arrived from another planet. Although the shape of El Topo is that of a Spaghetti Western, in particular the Man with No Name films, Jodorowsky superimposed these familiar genre tropes onto a surreal desert landscape that seems to be assembled from dreams and acid trips, and strewn with dialogue that invokes both Zen Buddhism and Christian symbolism. At over two hours, the film is nonetheless densely packed, cutting quickly from one outrageous image to the next. After a screening at the Museum of Modern Art, New York’s Elgin Theater picked up the film for midnight screenings, where it became a word-of-mouth hit. Adventurous audiences and celebrities flocked to the film to bask in the glow of its brutal philosophy. The images, the fast, hallucinatory editing, the psychedelic soundtrack – and probably even its awkward English dubbing – made the film a natural accompaniment to pot or LSD. Famously, John Lennon became one of the most outspoken fans of El Topo, asking record producer Allen Klein to purchase U.S. distribution rights to the film, and the Beatles’ own label, Apple Records, issued a soundtrack (Jodorowsky is credited with composing the score alongside John Barham). In the interview contained in the album’s gatefold, Jodorowsky attempted to explain some of his artistic vision: “I believe that the only end of all human activity – whether it be politics, art, science, etc. – is to find enlightenment, to reach the state of enlightenment. I ask of film what most North Americans ask of psychedelic drugs. The difference being that when one creates a psychedelic film, he need not create a film that shows the visions of a person who has taken a pill, rather, he needs to manufacture the pill.”

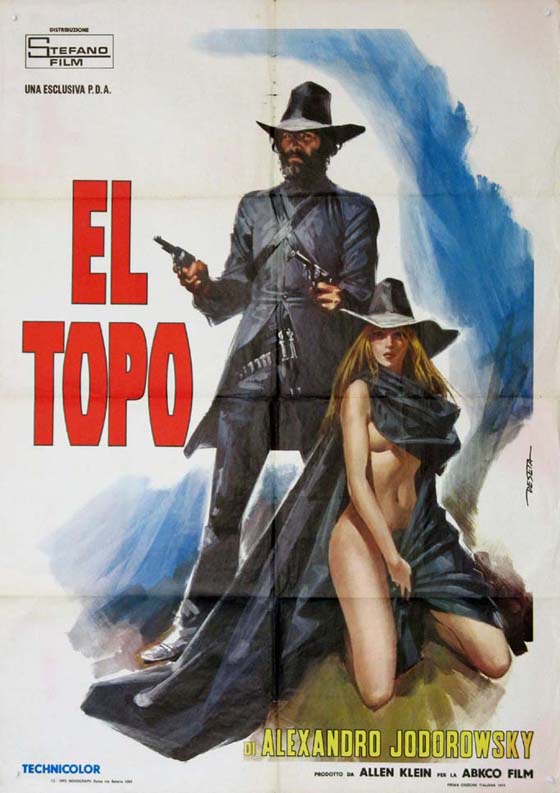

Alejandro Jodorowsky as El Topo.

Although El Topo brought Jodorowsky psychonaut fame, it was actually his second film, following Fando y Lis (1968), an adaptation of a play by Fernando Arrabal. Jodorowsky and Arrabal, along with cartoonist and novelist Roland Topor, had founded the Panic Movement in Paris. They would perform assaultive theater performances designed to outrage their audiences; they sought enlightenment through taboo transgression. Surrealism had become bourgeois, and Dalí had gone commercial, which left room for Panic to be proto-punk. They brought surrealism back to the anarchic spirit of Buñuel and Dalí’s scandalous screenings of Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L’Age d’Or (1930): the spectator wasn’t safe. With Fando y Lis and El Topo, Jodorowsky brought Panic to the cinema. (Arrabal, for his part, directed equally visceral Panic films beginning with 1971’s Viva La Muerte, which was promptly booked for the midnight movie circuit. Although Panic was officially dissolved in 1973, its spirit continued in their work.) But there is a difference between Jodorowsky’s first two films. Fando y Lis has the feel of a surrealist or absurdist play, a Waiting for Godot-style built-in inscrutability. Though it contains many poetic images, it’s difficult for the viewer to be anything but clinically removed from the action. On the other hand, El Topo is a Western. For the first half hour, a hero in black rides a horse through the wilderness, rounding up rampaging, raping, hooting-and-hollering banditos and shooting them through the head. Then he sets out on a quest to duel four Zen Masters in the desert, after cruelly abandoning his child to take up with a greedy, lustful woman named Mara (Mara Lorenzio), and a mysterious woman in black (Paula Romo), who may or may not be real. After the Masters have been vanquished, El Topo goes insane, and is shot by Mara and the woman in black. Inside a mountain occupied by exiled people suffering from deformities, he becomes reborn (almost literally, in one unintentionally funny image), and, after climbing free, he becomes a beggar in the nearby village run by fascists. He falls in love with a dwarf from the mountain (Jacqueline Luis), and embarks on a new quest: to dig a tunnel to set the crippled prisoners free. There is something essentially accessible about El Topo, even though its outlaw imagery ensures its appeal will be limited. A surrealist, mystical Western is an irresistible idea. It draws the viewer in before it tests their limits and takes them on Jodorowsky’s intended spiritual journey.

One of the four Masters that El Topo challenges to a duel, attended by a man with no arms and a man with no legs.

Even the opening title sequence, illustrations of a mole (“el topo”) clawing its way through dirt, makes its central metaphor explicit. “The mole digs tunnels under the earth, looking for the sun,” Jodorowsky narrates. “Sometimes he gets to the surface. When he sees the sun, he is blinded.” Though the film indulges in its own arcane, secret codes (honeycombs and bees are important, for example, and are used to represent miracles of sainthood), the plot is always clear, and many of the symbols are straightforward. Sometimes hilariously so. A stone fountain in the shape of a penis spurts water into the face of a delighted Mara. A lesbian overture from the woman in black involves shaping a juicy piece of cactus into a vagina shape. El Topo ascended so quickly in its status as a mystical work of art that critics – from Vincent Canby and Gene Siskel to, in more recent years, Alex Cox writing for Film Comment – were quick to attack its occasionally juvenile symbolism. But, in its own midnight-movie way, El Topo is populist. It’s not the mainstream surrealism that Panic attacked, but it does welcome all psychedelic pilgrims seeking enlightenment in a dispiriting late 60’s/early 70’s landscape of Vietnam, violence against peaceful protests, assassinations, corruption, riots and revolution. Much of the imagery evokes these current events, especially in the film’s final minutes.

El Topo meets the Third Master (Victor Fosado).

Significantly, Jodorowsky encourages all seekers to look inward and extinguish the violence within themselves. El Topo may send his seven-year-old son away with some tough philosophy (“Destroy me. Depend on no one,” he commands), but it comes back to haunt him. As one of the Masters in the desert warns him, “When you think you are giving, you are really taking away.” El Topo becomes a martyr, but only after recognizing his own inherent cruelty and devoting himself to helping others. He is actually one of the first in a long series of Jodorowsky father figures, whose tough love only damages the child, such as the literal scars the father leaves his son in Jodorowsky’s Santa Sangre (1989), or the generations of abuse depicted in the warrior clan of his outstanding graphic novel series The Metabarons. This point is often missed by critics of El Topo: Jodorowsky is not using the film to establish himself as a guru as some narcissistic act. His character needs to tear down his ego. Even when he remakes himself as a beggar, his act of kindness is in vain, and leads to the massacre of those he intended to save. The film’s only note of optimism is in the arrival of his new son, born at the moment of his death – perhaps he will end the cycle of violence and abuse and achieve good. Nevertheless, Jodorowsky would improve as a storyteller, and his first three films rely too much on strained symbolism – as mind-blowing as they can be. There’s also an unfortunate tendency in El Topo to equate homosexuality with corruption: the banditos molesting their captive Franciscan monks; the woman in black’s seduction of Mara. But despite its many weaknesses, El Topo sears itself into your brain – once you see it, you can never forget it. Though it is not completely without precedent – visually, it seems to owe much to Buñuel’s 1965 Simon of the Desert – there’s little doubt the film is a complete original, and announced to the world the arrival of a prodigious imagination and a stunning visual fabulist.

El Topo, reborn as a beggar, entertains the crowd with his companion, “The Small Woman” (Jacqueline Luis).

Jodorowsky’s partnership with Allen Klein would be both rewarding and devastating. Klein would go on to produce Jodorowsky’s wild follow-up, The Holy Mountain (1973). But when Klein made promises that Jodorowsky would next direct an adaptation of the popular erotic novel The Story of O, the filmmaker was disinterested, and refused. An angry Klein pulled El Topo and The Holy Mountain from American distribution, and over the years the feud only intensified. In 2001, Jodorowsky wrote a letter published in Ain’t it Cool News calling out Klein as a “cultural killer” for withholding his films. “What happens to me, happens to many artists. I think that murdering a work of art is as monstrous as murdering a human being.” I first saw El Topo by renting a Japanese import VHS from the storied Scarecrow Video in Seattle (and watched it as one should not, in the middle of a sunny afternoon). The tape was rare enough that a significant deposit was required in case of loss or damage. Jodorowsky and Klein finally reconciled in 2004; as the filmmaker described it at a Toronto screening of The Holy Mountain shortly thereafter, all the mutual hatred and resentment dissolved immediately with a face-to-face meeting, and they embraced. They became partners once again, and Anchor Bay won the rights to distribute both films on DVD (and, eventually, Blu-Ray) for Klein’s ABKCO Films imprint. Although Jodorowsky never needed a “comeback” – he has been a prolific author of books and comic books in the decades since 1990’s The Rainbow Thief – he seems to be enjoying just that with the release of two films: Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013), Frank Pavich’s documentary chronicling Jodorowsky’s aborted attempt to film Frank Herbert’s novel in the 70’s, and The Dance of Reality (La danza de la realidad, 2013), the first film since 1990 to find Jodorowsky in the director’s chair. An autobiographical work describing his childhood in Chile, the film stars Alejandro as well as his son Brontis, who rode El Topo’s horse buck-naked as a child. Talk is turning once again – as it has over the years – to a sequel to his most famous work, finally telling us what becomes of El Topo’s sons. (During the years of his feud with Klein, Jodorowsky claimed he would call his hero “El Toro” to avoid a lawsuit, his mole becoming a bull.) On the interview circuit to promote The Dance of Reality, he told The Dissolve: “Nobody wants to make the movie, because they think it’s too expensive, it’s too risky. So now I’m going to do it as a comic. This week, I have done the drawing, I have a fantastic person doing it…But I’m going to make another picture, it’s called Juan Solo, a gangster/mystical picture in Mexico. I have half of the budget already.” At 85, the Mole still continues to dig, dig, dig toward the blinding sun.

Apple Records LP signed by Jodorowsky and actor Robert John Skipper (El Topo’s son).