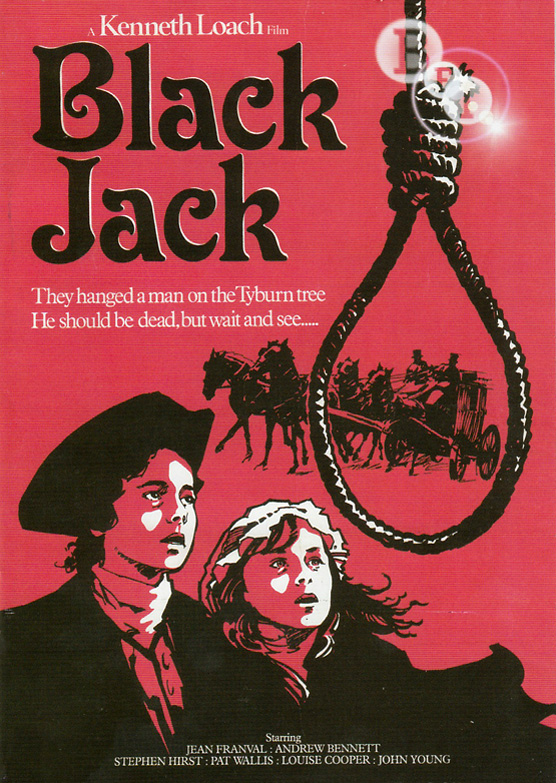

First we see the French sailor “Black Jack” (Jean Franval, Le Cercle Rouge) – no one can pronounce his true name – hanged for murder following a deadly tavern brawl, and his body is delivered to a widow who makes her money off selling unclaimed bodies to surgeons. (She’s one step removed from a body snatcher.) It’s 1750 York. Though it’s broad daylight, her home is draped in shadows, so we can barely make out what we’re seeing as the body is searched and relieved of its treasures. We can also barely make out what they’re saying: the dialogue is muffled, and the accents are thick. She leaves the body of Black Jack in the care of a young draper’s apprentice named Bartholomew “Tolly” Pickering (Stephen Hirst), who holds a candle over the dead body, and stares as suddenly old Black Jack starts to choke and stir. As the narrator informs us, Black Jack cheated the hangman’s noose by stuffing a bent spoon into his gullet, sparing his windpipe from being crushed. The man, a giant, shatters the window, seizes the boy, and drags him into the woods. So begins the “children’s film” Black Jack (1979), directed by Ken Loach (Kes), a harrowing, raw, and unforgettable work that has somehow managed to be forgotten – that is, until recent revival screenings and a British DVD release. I caught the film a few weeks ago at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and although normally I would take offense at subtitles in an English language film, here it truly makes a difference: Loach’s commitment to naturalism – coupled with the fact that the tight budget didn’t give him the chance to dub the film properly – renders much of the dialogue unintelligible (so much is whispered, mumbled, or drowned in esoteric slang). But Loach finds an accessible beauty in the roughness. The cinematography is by Chris Menges (Michael Collins), who relies upon natural lighting a la Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975), to which this film seems a close relative. Black Jack is a film that immerses the viewer in an authentic-seeming mid-18th century with all of its alien qualities intact. There isn’t a trace of sentimentality, but Loach’s approach establishes an astonishing intimacy, guiding the viewer to a deeply satisfying conclusion.

Black Jack (Jean Franval) seemingly rises from the dead before the eyes of young Tolly (Stephen Hirst).

Its inexact reputation as a children’s film comes from the source material, a 1968 children’s novel by Leon Garfield, who crafted a picaresque in the mold of 18th century novels. Indeed, Black Jack is a novelistic film – you can easily imagine chapter titles dividing the scenes. Black Jack begins to lead his young hostage into a career as a highwayman robbing coaches (Tolly does his best to thwart him), but they become sidetracked by a young girl named Belle (Louise Cooper), who is suffering from a fever that has given her short-term memory and occasionally violent tempers. Her family, thinking her mad, has sent her away to a sanitorium; but during the journey she wanders free, and becomes lost. Eventually she finds herself under the care of Tolly, who decides she’s his personal responsibility. The three fall into the company of a traveling fair that includes a fortune teller, a troupe of performing dwarfs (whom Terry Gilliam would soon cast as the Time Bandits), and an old charlatan, Dr. Carmody (Packie Byrne), who hawks a miracle cure for aging with the assistance of a boy named Hatch (Andrew Bennett), a budding con artist himself. While Black Jack sets out on a path toward redemption – with a few stumbles along the way – the boy Hatch proves far more dangerous, and a canny blackmailer when he uncovers Belle’s true identity.

Tolly and Belle (Louise Cooper), the girl he means to rehabilitate from her “madness.”

With Black Jack‘s documentary approach, the camera races to catch up with the characters as they move through woods or alleyways; it roves left and right as it strives to pick out its protagonists from the crowd, as though we are lost in the cacophony of 18th century village life, trying to decipher the dialogue amidst a tumult of competing voices and eccentric characters. Loach gathered a cast mostly of nonprofessionals. Its two young leads were ordinary schoolkids from working-class families: the son of a lorry driver and the daughter of a miner. Their unaffected performances give the film a surprising emotional weight. Free of any manufactured tension and without overt manipulation, the film earns a particularly grisly moment set in the claustrophobic sanitorium in its final reel, a scene that seems straight out of a horror movie (I was reminded of the Val Lewton picture Bedlam). But this is a marvelous little film, whatever the intended audience. The good guys win, the villains are punished, the sinners are redeemed, and the delusions of “madness” prove to be divine foresight – all delivered with the understated pragmatism embodied by Tolly, the draper’s apprentice.