Well, now Ken Russell had gone too far. It was one thing to cast Roger Daltrey as a rock star/sex-god incarnation of Franz Liszt in his ultimate nutzoid composer bio, Lisztomania (1975), a film that also featured Ringo Starr as the Pope. For his next project he would make the ultimate transgression: he’d sully the virgin name of Old Hollywood. Mind you, another controversial filmmaker named Ken (Anger) had done this already with his legendary celebrity-gossip book Hollywood Babylon (first published in France in 1959, and in the U.S. in 1965). And there was always a Hollywood tabloid press eager to expose the sins of the stars. But Russell was a British filmmaker targeting not just Hollywood but America. Valentino (1977), his treatment of the short and tumultuous life of silent-film sex symbol Rudolph Valentino, depicts an Italian immigrant whose portrayals of seductive foreigners with lithe bodies, greased hair, and plenty of talcum powder, left women swooning and men accusing the star of being suspiciously effeminate, a “pink powder-puff.” Russell’s idea of Valentino is a man who goes to such lengths defending his masculinity and his American patriotism that it ultimately kills him. The film is also chock full of MAD Magazine-style screaming caricatures, lunging at the camera with exaggerated period slang in costumes (by the director’s wife, Shirley Ann Russell) that are both elegant and surreal, in turns. Predictably, American critics did not embrace Valentino. Russell, almost as if by apology, would make his next film in America (Valentino was shot at Elstree Studios in England), but his attempt at a big-studio populist genre movie, the FX-heavy Altered States (1980), would prove a disastrous personal experience for the director, and effectively sealed the door to Hollywood’s golden gates. He’d remain an outsider filmmaker for the rest of his career, his large-scale spectacles behind him.

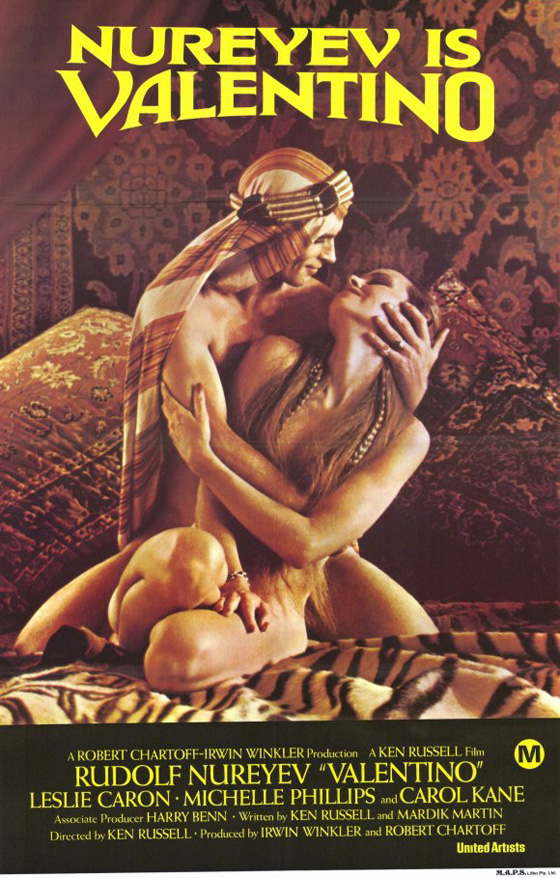

Natasha Rambova (Michelle Phillips) conducts some fortune-telling for her co-star Rudolph Valentino (Rudolf Nureyev) on the set of “The Sheik.”

Russell’s first controversial decision was to cast a Russian dancer as an Italian movie star. Rudolf Nureyev was a noted ballet dancer who famously defected from the Soviet Union in 1961 (and, sadly, would later contract AIDS, passing away in 1993). He certainly looks like Valentino, and is given the opportunity to demonstrate his primary talent in a handful of well-choreographed dance scenes: Valentino, like Nureyev, was a dancer before he was an actor. Nureyev’s Italian accent comes and goes from one line to the next, and as for his emoting, sometimes he seems to be performing to the balcony; though Russell encourages such performances, he typically hires such actors of such caliber (Glenda Jackson, Oliver Reed, and so on) that, at least in his best films, a happy medium is found between authenticity and excess. Seeing as the entire film rides on Nureyev’s performance, Valentino stumbles. He simply doesn’t draw us into Valentino’s inner world, so the film leaves one cold. (One could argue that his acting method of expressing himself through his body is a tribute to the techniques of silent film stars. But I wouldn’t go that far. Overacting is overacting.) Russell doesn’t stop there; he also cast Michelle Phillips, she of The Mamas and the Papas, as Natasha Rambova, Valentino’s co-star, wife, fortune teller, and career counselor. This was not Phillips’ first acting role: she had a significant role in John Milius’s Dillinger (1973), and a few smaller roles in film and TV before embodying the most important woman in Valentino’s life. She sells it, rolling with every wild tonal shift – first charming, wise, and seductive, and in later scenes gazing into crystal balls and giving herself over to raving delirium. For Phillips, it was just the start of a long and fruitful acting career. Other players include the great Leslie Caron (Gigi, An American in Paris) as the actress/writer/film producer Alla Nazimova; Seymour Cassel (Faces, Rushmore), wonderful here as Valentino’s late career manager George Ullman; and Carol Kane (The Last Detail), Peter Vaughan (Straw Dogs, Brazil), and John Ratzenberger (of Cheers and just about every Pixar movie).

Natasha Rambova at Valentino’s funeral.

Russell attempts to circumvent the usual biopic pitfalls by applying a framing device: Valentino’s funeral, where crazed fans storm the funeral home while the desperate staff tries to board up the windows with coffin lids. As the people in Valentino’s life arrive to pay their respects, Russell treats us to a This is Your Life, Rudolph Valentino, and we see the different phases of the actor’s career from the perspective of those who knew him (primarily, his women). But though it’s an admirable effort, this storytelling technique doesn’t really solve the essential problem of the biopic: we’re still privy to the ups and downs of his life with little narrative momentum. The first stretch of the film is pretty dire: lumpy, confusing, and off-putting. One particularly excruciating scene involving a celebrity named “Fatty” (Arbuckle, one presumes), who tries to humiliate Valentino with joy buzzers and braying laughter. But the film improves as it goes along, and sparks to life with some imaginative scenes that should be bookmarked for any Russell clip reel. First among these is a beautifully cinematic sequence in which Valentino’s initiation of a love affair & business commitment with Rambova takes place on the outdoor desert set of The Sheik, the actors in their Arabian costumes until they begin a striptease (of equal-opportunity nudity, it should be noted). The sequence demonstrates Russell at his best: wit, invention, and a perfect fusing of subject matter with style. Later, Valentino’s termination of his contract with Jesse Lasky (Huntz Hall, The Phynx), of Famous Players-Lasky, takes place on the set of a Western with a series of visual gags enacted just over Lasky’s shoulder. This is how you enliven a stock dialogue scene. Russell also stages some enthusiastic – and convincing – recreations of Valentino’s greatest celluloid hits.

Alla Nazimova (Leslie Caron) arrives at Valentino’s funeral with style.

Ultimately, though, the film overstays its welcome, and by the time we are witness to an elaborate boxing match between the actor and a member of the press – the star’s last-ditch effort to prove his masculinity to the public – Valentino seems as dizzy and punch drunk as its subject. This boxing match really occurred, amazingly enough, though it’s unlikely it was anything like the way Russell stages it. The film also reimagines the bout as being the last night of Valentino’s life, which puts the director’s thesis to the foreground: that America tore this Italian immigrant to pieces. (Before the match begins, the Star-Spangled Banner is played, and as Valentino pointedly salutes the flag, the stars and stripes fill the screen.) So thematically Valentino‘s climax is on target, but by then the film has become exhausting. Is it the bomb that its reputation suggests? Not at all. Hollywood historians will quibble over the details, but there’s still enough pure filmmaking on display to allow Valentino to stick in the memory. Russell was a talent, but critics didn’t know what to do with his wild energy – here amplified as he aligns his cinematic sensibilities with Jazz Age excesses of cocaine and sex (and one silver platter stuffed with French fries and gallons of ketchup). Only in retrospect is it easier to appreciate just what he was trying to do. It may not be a stellar biopic, but it’s an appropriate capper to Russell’s eye-popping 70’s spectacles.