The most famous monster movie ever made has aged so well because it is about awe and wonder. That is the topic of King Kong (1933) and its method. Obviously, it is still a film from 1933 – every film is of its time, and will reflect its time, which becomes more evident with the distance of years. It’s a pre-Code film (and it shows); it’s an early sound film (and it shows); it’s a breakthrough work of pure special effects magic, and that shows, too. But it endures because of how it deploys that magic. It builds slowly but steadily, beginning in New York and carrying us on the sea voyage to Skull Island. We don’t even know, at first, where Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong) is taking his new starlet, Ann Darrow (Fay Wray), though we know that he’s a filmmaker who also fancies himself an explorer and adventurer – an autobiographical note by producer and co-director Merian C. Cooper, who embarked on expeditions to shoot location footage for his previous films Grass (1925), Chang (1927), and The Four Feathers (1929). Then he unfolds his map, drawn by someone who glimpsed Skull Island, and we see a crude outline of the landscape that will become so real to us as the next hour unfolds: a village on a beach, a wall separating the village from the rest of the island, and a giant shape marked “Skull Mountain.” We’re told the villagers worship a deity called “Kong” – and Denham wants to get past that wall to see what it is. We get a solid half hour of anticipation and promises before the film suddenly delivers – and delivers, and delivers, for the rest of its running time, relentlessly. Because past that giant wall lie wonders, and Ann Darrow is kidnapped and dragged, along with the audience, right into them.

Robert Armstrong, Frank Reicher, Fay Wray, Bruce Cabot, and fellow explorers discover the lost tribe of Skull Island.

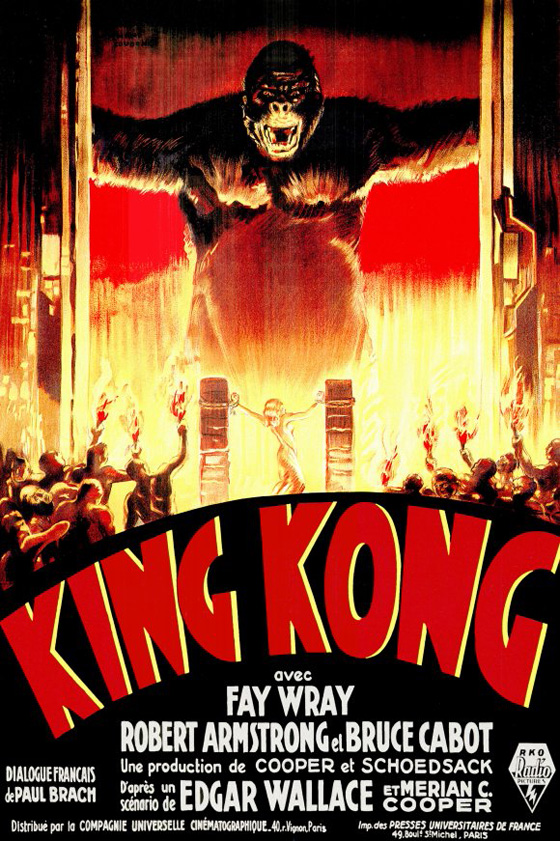

Cooper wanted to keep Kong’s identity a secret in the advance publicity campaign. Kong, a 50-foot ape brought to life through the stop-motion animation of Willis O’Brien (The Lost World), is now one of the most iconic monsters the cinema has ever given us, and the climactic scene of Kong straddling the Empire State Building has been imitated and parodied for decades. But imagine seeing this film fresh, and having no idea what Kong is. There is real terror as Ann Darrow has her wrists bound to two stone monoliths, a sacrificial altar to the god of Skull Island. The gates are closed, and for a moment she is on the other side, locked away from us – doomed. Then we see her horrified face, hear the classic Fay Wray screams, and out of the foliage crashes this colossal creature. He has dark fur on a slightly pointed head, bright angry eyes, and sharp white teeth. There seems to be something unnatural in the thing, the subtly erratic way it moves – an unreality that gives it the spark of fantasy, as Ray Harryhausen would later describe his own stop-motion. Darrow is helpless and her would-be rescuers are far away, and with the arrival of this impossible ape, the world has suddenly turned inside-out. We’re on the other side of the wall, and anything goes. When Denham and John Driscoll (Bruce Cabot) finally arrive, the altar is empty, and they must traverse the uncharted jungle. And that’s when we get dinosaurs – and in generous amounts!

Kong approaches Ann Darrow (Wray).

We are in the age when special effects are no longer special, though I’ll spare you the anti-CGI rant. It’s ultimately a good thing that CG allows us to visualize whatever we wish on the screen. Cooper dreamed up Kong wholesale from his imagination, and hired director Ernest B. Schoedsack and Willis O’Brien to bring his pipe dream to life. If he had access to CG, he would’ve used it. But Cooper and Schoedsack also knew that anticipation was half the formula, and awe was the goal. This is storytelling. Some of the better monster films in the post-CG age (Jurassic Park and Gareth Edwards’ new Godzilla come to mind) try to establish a grounded reality first, then prepare us for the possibility of wonders, and only then deliver on the fantastic. It allows us to participate in the process. It allows us to truly think about what it would be like to be there, confronting towering creatures. When Kong battles an allosaurus in a jungle that resembles a Gustave Doré illustration, we are lost in the storybook quality, indulgent, “suspending our disbelief.” But also note that Schoedsack and Cooper continue to cut to Ann Darrow perched in a tree: we’re seeing events from her point of view. When the allosaurus throws Kong into the trunk, toppling it, the camera joins her for the whole screaming ride down to the forest floor.

Bruce Cabot pursues Kong through Skull Mountain.

As to the nonstop action of the last hour of the film, this is commonplace now but was quite new in its day. There are a few reasons it never grows tedious. One is that there is a constant supply of imagination on display: the setting keeps changing, most dramatically from Skull Island to New York City (with only a short breather in-between). But the other is the film’s relationship between Ann and Kong. The curious scene in which he strips off part of Ann’s clothes while she lies unconscious in his paw has the simultaneous effect of horrifying the audience, making them laugh, and giving them sympathy toward Kong. He gets away with all this because he’s an ape, of course. We have watched him protect Ann through the various dangers of Skull Island, and now we see him fascinated by her – we see the primate connect with his human side. This relationship reaches its famous apotheosis upon the Empire State Building. In his death throes, he takes the time to pick her up, tenderly gaze at her, and then set her back down again. It speaks to the artistry of O’Brien that he can sell this scene with the gestures of a small armatured model. Truthfully, Cooper hits the “beauty and the beast” theme a bit too hard in this film (from the opening “Old Arabian Proverb” to the film’s famous last line), but when it counts, O’Brien realizes the potential of the theme and turns Kong into the tragic hero of the film. We know Kong is a herky-jerky little puppet. We know he isn’t real, and all the fantasy is just that. But in the spell of the silver screen and the darkened theater, we are in awe at King Kong. That it still works just as well eighty-one years later is an achievement.