Following his rather remarkable children’s educational film Journey to the Beginning of Time (Cesta do pravěku, 1955), Czech animator-turned-director Karel Zeman tripled his ambition for a loving tribute to the Voyages Extraordinaires novels of Jules Verne with Vynález zkázy (An Invention for Destruction, 1958). In 1961 the film was belatedly released in the U.S. as The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, by which time the film had won numerous awards around the world, including the International Film Festival’s Grand Prix at the Brussels World’s Fair. (I will refer to the film by its common English-language title for the sake of simplicity.) The film has remained undeservedly obscure in the U.S., but those with a region-free DVD player can seek out the 2012 DVD released by the Karel Zeman Museum (uncut and with English subtitles), readily available online. I recently did so after acquiring a Fabulous World of Jules Verne U.S. release poster at the Horrorbles shop in Burwyn, Illinois; I knew what the film was, but felt that I should finally get around to watching it (now that I have the poster framed and hanging behind a model Nautilus!). After watching the DVD, I kicked myself for delaying so long. Zeman’s film is a revelation. To say it has aged well is an understatement. Rather, it seems to exist outside of time; I would defy someone to watch it and guess the year it was made, or the decade. This is largely because Zeman’s multitude of special effects techniques have one goal in mind, which is to create a film that looks exactly like the steel engravings of first-edition Jules Verne novels of the late 19th century. (Watching the film, I was anachronistically reminded of Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin’s oeuvre recreating the texture of silent films and early talkies, but most of all – believe it or not – Robert Rodriguez’s Sin City, in service to the ink-drenched illustrations of Frank Miller.) Consider that Zeman’s film followed the release of Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), which is just about the best Verne adaptation one can hope to receive. The Disney film may condense the novel, but it’s nonetheless very faithful, with a perfect and charming cast, and rendering Verne’s proto-steampunk world with realism in big-budget, Technicolor Cinemascope; it’s simply one of the greatest fantasy films ever made. Zeman, four years later, gave the world a different Verne tribute: one that eschews realism. If Walt Disney delivered a believable Verne world, Zeman’s “fabulous” world is intentionally two-dimensional, black-and-white, borderline surreal. He just wants to see those Victorian-era illustrations move. So he animates them in miniature, builds full-scale sets flat and painted to resemble pen-and-ink drawings, shoots through aquarium glass. He places his actors inside this collage; and, when he has to, he replaces them with cut-outs or puppets. Anything to achieve the look of those illustrations. Reality has no place here.

A flipper-propelled submarine conducts an undersea search.

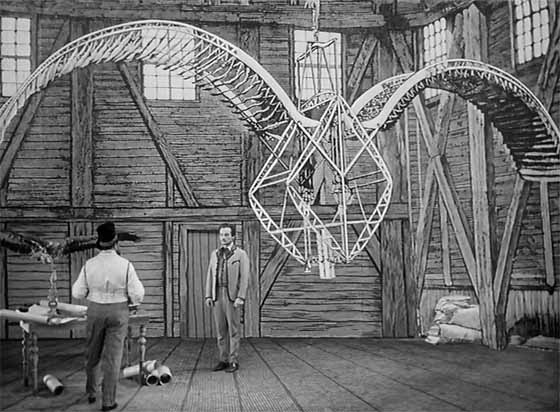

The plot only briefly touches on Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, giving us a few highlights from that book. It actually adapts a deeper cut, seldom reprinted, the 1896 novel Facing the Flag. (Verne wrote a lot of novels.) The story concerns Professor Roch (Arnost Navrátil), who discovers a means to unlock great power, but when he’s kidnapped by the sinister Count d’Artigas (Miroslav Holub) – who rams and pillages ships using his Nautilus-like submarine – his discovery is used to built a “Supergun,” a mammoth cannon which can sink the ships of any navy. The Count keeps the professor at work on an island with a lagoon in its center and a smoking volcano. He also imprisons our hero, Simon Hart (Lubor Tokos), and the beautiful Jana (Jana Zatloukalová), whose ship was wrecked by the pirate. The somewhat generic pulp-adventure plotting does offer relevant parallels to the corruption of human ingenuity with the development of atomic weapons, but message aside, the story is really just an excuse for Zeman to apply as many exotic Verne visuals as possible. He begins the film with Simon Hart observing a submarine from the deck of a steamship, and casting his gaze upward to see a man in a pedal-operated flying machine. Later, we will see underwater bicycles used by the Count’s men for their oceanic expeditions; the professor’s towering industrial factory; a large robotic arm that delicately hands the Count’s henchman a pen; the Count’s castle perched on a high crag in the island; a miniature submarine that propels itself with flippers; and other assorted wonders.

Simon Hart (Lubor Tokos) is shown a flying machine in the Count’s island lair.

These come to us courtesy stop-motion animation, cutout animation (in the style of a Terry Gilliam cartoon), models, forced perspective, trick sets, live action location photography, and optically matting any variety of the above. In fact, Zeman’s favored technique seems to be getting at least two or three layers of effects in the same frame, overwhelming the viewer visually to increase the challenge of determining just how all this was accomplished – and, of course, making the effect all the more convincing. Convincing, that is, of 19th century illustrations come magically to life. Horizontal lines stretch across the skies, and the rays of the sun are diagonal lines extending out of the heavens. Costumes are decorated in black stripes to further the illusion that the actors are part of the drawing. The seas are wavy lines projected onto the surface of water. (I may have that detail wrong. That’s what it looks like.) The cumulative effect is that everything you see was made from pen and ink, but now it moves. When Zeman was a child reading Jules Verne, those illustrations would have meant everything – amidst pages and pages of words, a tantalizing porthole view of the world Verne is describing. Zeman’s film indulges his younger self by letting us pass through that porthole, to swim with him among the fantastic.