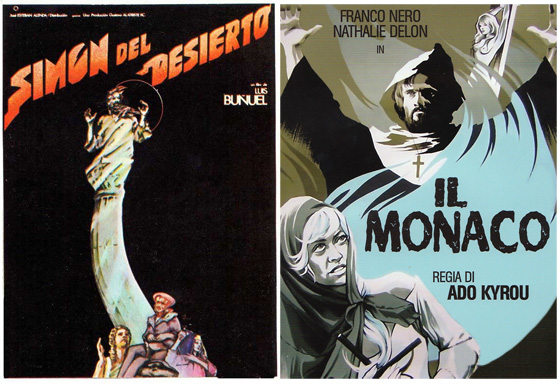

Luis Buñuel had come out of the desert with Viridiana (1961). Since 1945 the Spanish-born enfant terrible behind the definitive works of Surrealist cinema, Un Chien Andalou (1929, with Salvador Dalí) and L’Age d’Or (1930), had been living in Mexico, creating commercial films as well as the occasional below-the-radar masterpiece (Los Olvidados, The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz, Nazarín). Viridiana saw Buñuel, whose profile was bolstered by the quality of his Mexican films, returning to Franco’s Spain to create a film so scandalous (and blasphemous) that it would outrage the government. Nonetheless, the film – about a would-be nun who pays a disastrous visit to her uncle – made the director a hot property again. He returned to Mexico to film the elegantly surreal satire The Exterminating Angel (1962), and in France made Diary of a Chambermaid (1964) with Jeanne Moreau. Diary of a Chambermaid was co-written by a young writer named Jean-Claude Carrière, who would become a loyal collaborator with Buñuel. They set to work on a screenplay based on Matthew Lewis’s 1796 Gothic novel The Monk, concerning Ambrosio, a monk in Madrid who is led step by step into witchcraft, rape, and murder. The film was to reunite Buñuel with Moreau. As John Baxter writes in his 1994 biography Buñuel, “He was less interested in the sensational plot than the forces that might drive a religious zealot to depravity. Visits to Spain had reminded him of the asceticism and self-denial of monastic life. Much as its calm drew him, he knew that sexual hallucination and sadomasochistic frenzy often festered in its isolation.” Repression, hypocrisy, and fetishistic lust – the usual bag of Buñuelian obsessions – would have been engaged to the full. But the resulting screenplay was set to the side as the director was lured by producer Gustavo Alatriste to make his next film Simon of the Desert (Simón del desierto, 1965).

Disciples – and a bemused goatherder dwarf – pay a visit to Simon of the Desert.

The film would indulge the atheist Buñuel’s fascination in Christian asceticism, but unlike The Monk, Simon of the Desert would depict a man who does everything he can to resist temptation. The director was inspired by tales of “stylites,” holy men who climbed pillars to isolate themselves from the world and come closer to God, in imitation of Simeon Stylites, who did just this – for thirty-seven years – in 5th century Syria. In José de la Colina and Tomàs Pérez Turrent’s Objects of Desire: Conversations with Luis Buñuel (excerpted in the Criterion DVD liner notes), the director enthuses that he was turned on to the stylites by his late friend Federico García Lorca (assassinated in 1936). Lorca had recommended the thirteenth century book The Golden Legend, which describes lives of the saints, and both relished the volume’s naïve mix of the sacred and the scatological. “‘Shit flowed down down the column like wax drips from candles,'” recalled Buñuel, floridly embellishing the original text. “It’s an enticing image, isn’t it?” Buñuel’s riff on Saint Simeon opens with a stylite named Simon (Claudio Brook, The Exterminating Angel), who has been standing on his pillar in the desert for six years, six months, and six days, transferred to his latest, taller pillar, donated by a wealthy local. A ceremony is held, and disciples arrive in droves. As Simon descends the pillar and humbly accepts his new one, someone tears off a fragment of his robe as a souvenir. The idea of receiving a pillar upgrade is rich with satire, but it’s actually taken directly from The Golden Legend: “Then his neighbors came thither by devotion and enhanced his pillar four cubits of height, and there he dwelled seven years after, and after, they made to him another of twelve cubits of height, in which he dwelled, and after that they made another of twenty cubits, and after that another of thirty, and there he abode four years…” By simply reasoning what this would entail – his “realism” – Buñuel turns the text into a comedy. In one passage of The Golden Legend, Simeon’s mother visits him, though she has been forbidden to do so. Simeon remarks that she may remain and it will be seen if it pleases God (not long thereafter she dies in her sleep!). In Buñuel’s version, Simon’s forlorn mother (Hortensia Santoveña) is ignored, because, as Simon says, he belongs only to God now. Only in a brief, Last Temptation of Christ-style reverie do we see Simon in his mother’s arms; but, shaking himself from this daydream and determined to do God’s will, he continues to disregard his mother’s presence.

Simon (Claudio Brook) atop his pillar.

A young priest gently teases Simon as he delivers frugal rations, and Simon, scornful of the way the youth merrily skips away, nonetheless is tempted to descend to the earth to enjoy earthly delights. It’s not long before the Devil arrives, in the form of beautiful Sylvia Pinal, star of Viridiana, in a schoolgirl’s outfit. She exposes her breasts, pulls at his beard, licks his face. He endures her temptations, in various disguises (including as a bearded Jesus Christ carrying a lamb), and is equally vexed by other visitors. Buñuel portrays Simon as both admirable and absurd, dedicated to a task that begins to lose its meaning. He gets so carried away at issuing blessings that he blesses a fly and a piece of food stuck in his teeth. “I’m beginning to realize I don’t realize what I’m saying,” he says in his delirium. When he does perform a miracle – restoring hands to an amputee – the man promptly uses them to shove his daughter. In a scene that anticipates the Sermon on the Mount sketch in Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), the spectators are unimpressed. “See that?” “What?” “That thing with the hands.” “Oh, that.” Holiness and miracles are wasted on humanity, with our jealousies, quarrels, lust, and frivolity. “Your unselfishness is admirable and very good for your soul,” says one priest, “but I fear that, like your penance, it is of little use to man.” As in Nazarín, Buñuel’s corrupt universe has no room for would-be saints. Simon’s efforts to cut himself off from the sinful distractions of civilization are thwarted at every turn; until, finally, he’s transported by Satan to a nightclub in modern-day New York City, where nubile teenagers dance the “Radioactive Flesh”: the Apocalypse with deafening rock and roll. One of the central jokes of Simon of the Desert is that even quiet solitude is a vain quest.

Sylvia Pinal as the Devil, disguised as Jesus.

Buñuel began shooting the film in the Mexican desert, but production came to an abrupt halt when Alatriste ran out of money; with the allotted $120,000 spent, Buñuel improvised the hasty nightclub conclusion. The film runs 45 minutes. According to Bill Krohn’s Luis Buñuel (Taschen, 2005), abandoned were scenes of another pillar transfer (to a 60-foot one overlooking the ocean) and a visit from the Emperor of Constantinople. Even the new ending had to be altered: after Pinal states that Simon can’t return to his pillar because it has a new occupant, Buñuel would have cut to an advertisement posted at the top of the column, which then would have exploded, ending the film. Instead, we’re left with Pinal’s manic scream as she dances amidst the teenagers, a jaded Simon (in beatnik garb) looking on – which, turns out, is a conclusion that’s memorable enough. The truncated Simon of the Desert was intended for a diptych film, produced by Alatriste, to be called Two Free Movies. The second half of the film might have belonged to any name from a who’s-who of 60’s cinema – those bandied about include Stanley Kubrick, Vittorio de Sica, Jules Dassin, Akira Kurosawa, and Federico Fellini (Buñuel’s preferred choice). According to Baxter’s book, Orson Welles may have come closest to completing the bill, agreeing to the proposal on the condition that Alatriste fund Welles’ frustrated Don Quixote film: “Some time later Welles wired Alatriste that he was ready to start. Alatriste never answered.” Alatriste sat on the orphaned short, and Simon of the Desert wouldn’t see a proper release until the 70’s.

Ambrosio (Franco Nero) becomes obsessed with young Antonia (Eliana De Santis) in “The Monk.”

Following his elaborate religious satire The Milky Way (1969), the director again considered filming that script for The Monk that he’d written with Carrière. Fate intervened once more, and he made Tristana (1970) instead (marking his defiant return to Franco’s Spain). He lost interest in The Monk, and sold off the script to producer Henry Lange (Daughters of Darkness), who gave it to the Greek-born Ado Kyrou (The Roundup) to direct. Kyrou’s interest in surrealism extended to writing a book on the subject, Le Surréalisme au cinema (1953), so he was quite familiar with Buñuel and all other practitioners of Surrealist film. With Buñuel’s name attached to the script, The Monk had an air of prestige, and attracted, as its stars, Franco Nero (who had recently appeared in Tristana, but these days is best known as the original Django), renowned stage actor Nicol Williamson, and Nathalie Delon, recently divorced from Alain Delon (who appeared with her in Le Samourai). Nero plays the monk Ambrosio, whose fall from grace is one of the most spectacular in literature. He learns that one of his close friends in the monastery is actually (and quite obviously) a woman, named Mathilde (Delon). Despite his misgivings, they’re soon having a secret affair. When his liberated lust wanders toward a young girl named Antonia (Eliana De Santis), whose sick mother he comes to visit, he imagines, falsely, that she loves him back. She spurns his lascivious advances – and her mother bans him from their house – so he turns to Mathilde, who is actually a sorceress. She summons the Devil (a handsome hippie with a glow-in-the-dark shirt), who lends Ambrosio a myrtle bough whose properties are essentially the same as a modern-day rape drug. But before he can rape Antonia, he is discovered by her mother, whom he quickly murders. He flees into exile – like Simon, in permanent penance – but Mathilde draws him back into sin, this time in the castle of a Duke who’s also a sadist and pedophile (Williamson). It’s the Duke who brings the innocent Antonia back to Ambrosio, but once more things don’t go according to plan.

Ambrosio, in exile, is visited by the sorceress Mathilde (Nathalie Delon).

The novel ends with Ambrosio, desperate to escape the tortures of the Inquisition, finally succumbing to Mathilde’s insistence that he sign over his soul. He is transported by the Devil into a desolate wilderness, where it’s revealed that Antonia, whom he has murdered, was actually his sister; then he is dropped onto a rock that pierces his body, and he suffers for a few paragraphs more before dying. Buñuel and Carrière, who largely adapted the novel with accuracy (though trimming its subplots), made a significant Surrealist departure in their finale. After Ambrosio signs his name in blood, the Inquisition, arriving in the chamber to conduct him to more tortures, now look at him with new eyes. They tell him his audience awaits, and escort him through a curtain. Then – as with Simon in the Desert – we are transported to the present day. A vast throng has gathered to see the Pope: Ambrosio, raising his hands to greet them. Fin. With the exception of this denouement, The Monk‘s script (at least, as it’s been filmed) lacks the ironic wit that characterizes so much of Buñuel’s work. It also lacks Buñuel’s visual style – or any sense of style at all. Kyrou may be thanked for finally bring The Monk to screen, but he fails to bring any life to the material – it lacks the impish spirit of both Buñuel and Matthew Lewis. Scenes are drearily shot, and even moments of the fantastic or lurid lack the necessary spark to make them sufficiently stand out from the everyday. The final joke feels unearned (and also cheaply done: stock footage followed by a shot of Nero in a Pope costume). Nero, Delon, and Williamson (in his “eccentric” mode) do what they can, but it’s hard not to think that every Buñuel film contains hundreds of striking images, and this film doesn’t contain a single one. The Monk offers a fascinating “what if” – a lost Buñuel film, imperfectly realized. But you don’t need to look too closely to see Matthew Lewis’s original scattered about the director’s filmography – Viridiana (with Don Jaime drugging Viridiana so he can have his way with her), Tristana, The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz, Simon of the Desert, and many of his other films echo Lewis’s themes of hypocrisy, sexual repression, and the Church. In a certain sense, The Monk was never far from Buñuel’s work: he filmed his own variations, embellishments, and tributes many times over.

Note: True story – while writing this, I spilled coffee on myself, my desk, and a Buñuel book. After cleaning it up and drying the book, I poured myself another cup, opened a different Buñuel book, and resumed writing. I then spilled coffee again, all over the desk, all over my clothes, but barely sparing the second book. After stripping off my sopping clothes, I discovered that my dog had dropped a dead rabbit onto the back porch, and was beginning to eat its flesh. I darted outside in my underwear, lifted up the dog, and carried her inside. Grabbing a robe, I walked back out to retrieve the rabbit. Flies were circling the carcass, and one landed upon its unblinking eyeball. As I removed it to the trash, it was inescapable: I had found myself inside a Buñuel film.