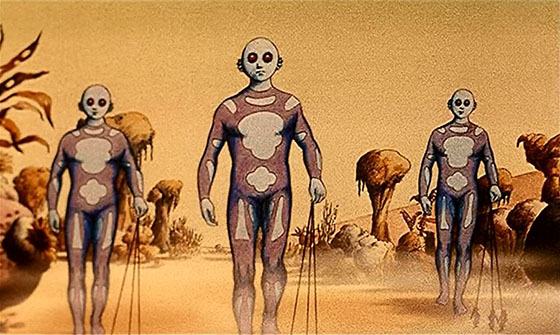

Fantastic Planet (La planète sauvage, 1973) establishes its theme in its very first moments. A mother is clutching her baby son to her chest, running for her life from something. She suddenly encounters a giant blue finger, which pushes her back. Then it flicks her away, sending her rolling like in a game of marbles. This continues until the blue hand lifts her off the ground and away from her son, then abruptly lets her drop to her death. A cut to a wide shot reveals the actual scope – and scale – of the situation. Three towering alien children, Draags, are bent over the mother and her child, studying them. It was just a game of marbles – to them, anyway. “She stopped moving,” says one of the children. “Now we can’t play with her anymore.” Along comes Master Sinh, leader of the Draag council, and his daughter Tiwa. She adopts the little child – an Om – for her own. To the Draags, on this planet called Ygam, the Oms (pronounced in the film’s French as hommes: men) are vermin, and only cute playthings at best. The Om boy, whom Tiwa names Terr for the planet where the Oms originated (Terra/Earth) is raised as a “tame Om,” dressed in ridiculous costumes and given a controlling necklace which keeps him near. But she makes the fateful decision to educate Terr through a knowledge “headphone,” and when Terr finally escapes one day, headphone in tow, he shares his expansive learning with the tribe of “wild Oms” that live beneath the Big Tree. Knowledge sparks an uprising, as well as a plot to escape to the mysterious neighboring planet which they only call La planète sauvage.

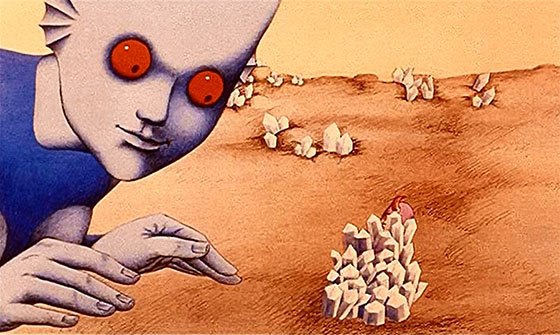

Tiwa lets her pet Om, Terr, wander into a dangerous landscape of spontaneously erupting crystals.

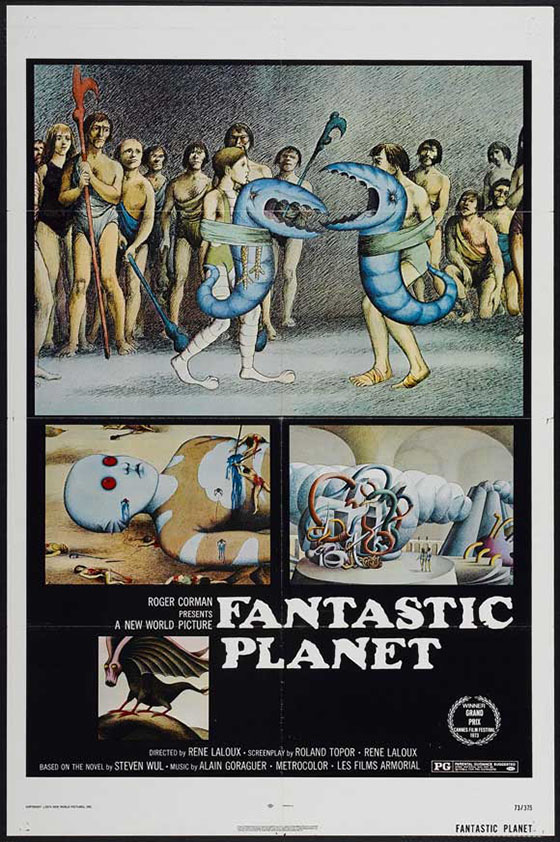

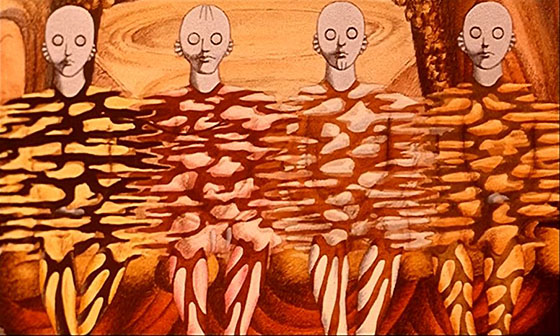

Based on the 1957 novel Oms en série by Stefan Wul, Fantastic Planet is a Czech co-production directed by French animator René Laloux, who would go on to two more feature-length, science fiction animated films, Time Masters (Les Maîtres du temps, 1982) and Gandahar (1988), which together form a loose trilogy. It’s a unique body of work, certainly in non-Japanese animation: adult, psychedelic, intellectual, occasionally coldly erotic, influenced by European comic books and SF paperbacks. All three films have whimsical interludes pondering xenobiology and xenobotany, which Laloux uses as an excuse to demonstrate a sauvage imagination reminiscent of Lewis Carroll. In Fantastic Planet, he frequently pans across the flat landscape of Ygam like some alien transmission of Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom. We see a turnip-like creature suspended in its own cage, throttling winged animals with its tentacled snout and scattering them about its feet, cackling sadistically. A desert of intestine-like shapes curl suddenly upward when moistened by rain, threatening the Oms that are passing through. A bat-winged anteater lands upon an Om dwelling and draws the Oms out with its long tongue. Feral creatures with snapping jaws are strapped to the Oms’ bodies for a duel to the death. And in the city of the Draags, the blue giants practice mysterious rituals such as Imagination, in which their bodies transform in unison as their minds psychically meld, or Meditation, where they astral-project themselves into floating spheres that hover over their bodies, and sometimes drift out of an egg-shaped temple and through the atmosphere like soap bubbles.

The Draags deploy gas in an attempt a “De-Om,” led to the Om dwellings by tame Oms in gas masks.

When Tiwa lets Terr first wander into the wild, he becomes snagged in spontaneously-forming crystals. As part of his ongoing education, she teaches him that whistling can make them shatter. He tentatively begins whistling the main theme to Fantastic Planet, shattering crystals left and right. The music, by Alain Goraguer (formerly associated with the 60’s French pop scene), is a psych/prog classic, and still finds its way into print on CD or vinyl every few years. It helps that the film is an enduring piece of cult cinema, indelible with its original visual style. Laloux’s Czech animators use cut-out animation – smoother than Terry Gilliam’s, but not far off – which looks like colored pencil drawings from an artist’s sketchbook. The designs are by Roland Topor, a cartoonist and author who was part of the notorious Panic movement with Alejandro Jodorowsky and Fernando Arrabal. (Topor’s illustrations are seen in the opening credits of Arrabal’s Viva La Muerte, 1971.) He also wrote the novel that was adapted into Roman Polanski’s The Tenant (1976), and played the Renfield character – an inspired bit of casting – in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu (1979). Laloux makes the most of Topor’s drawings, with trees that lash like whips, a Draag vacuum cleaner that brutally sucks up the Oms as part of an extermination effort, and a climactic visit to the “savage” planet where giant, nude, headless statues join with the Meditation spheres and dance together in a mating ritual between the Draags and out-of-body visitors from some other distant world.

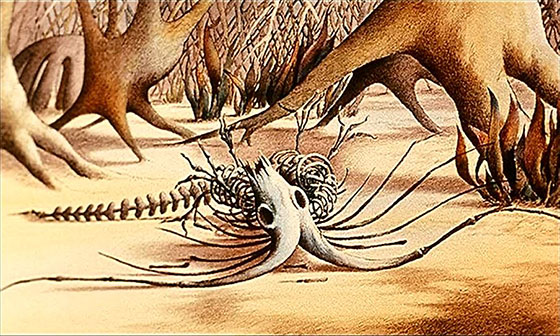

The skeleton of a flying anteater which threatened the Om tribe.

For all its strangeness (and exposed, PG-defying female nipples), this is a film that will not die. After the film won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 1973, Roger Corman’s New World Pictures distributed a dubbed version, which became a video store staple through the 80’s; as a youngster, I rented it to general bafflement. (Still, when I saw the imported and edited version of Laloux’s Gandahar, now called Light Years, I could intuit they were from the same director, pre-IMDB. I strongly disliked Light Years until I finally saw the original French version much later, and came around.) The film is frequently screened, occasionally with live music accompaniment, or otherwise appropriated by adventurous artists who saw the film at a critical moment and have been bemused, stirred, or inspired. But watching the film again, I am struck that it has its own rhythm – brutal and childlike, meditative and raw, a series of contradictions spread across 70 minutes. The only films to which it can be compared are those directed by René Laloux. Perhaps he came floating to us in a sphere from some other world, temporarily parting with his dancing statue.