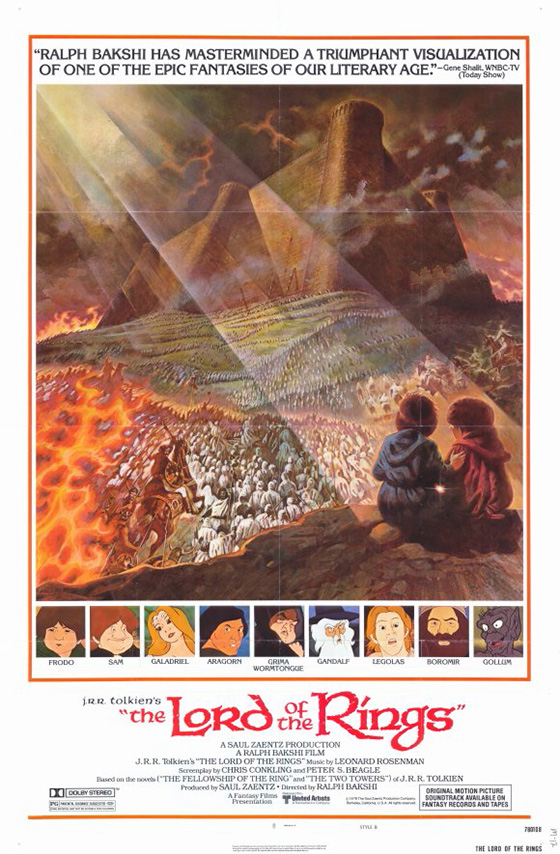

It should be clearer now that Peter Jackson has completed his Hobbit trilogy that the Middle Earth omnipresent in his films, the spin-off video games, and miscellaneous merchandise – the Middle Earth that we currently breathe in our pop culture – is the Peter Jackson interpretation only. It’s not definitive; it’s a take on the material, and we can see what that entails, for all its strengths (special effects, attention to detail, smart casting) and weaknesses (cartoonish and overlong action sequences, bloat). Moreover his six films are products of the early twenty-first century. Now that the dust is starting to settle, it’s easier to discern them as examples of the modern CG-laden blockbuster, initially helping to set the model, and now, with the Hobbit films, feeling self-imitative. Big-budget fantasy films will look different in another ten, twenty years; these films are of their times, despite how important and influential they are (and certainly his Lord of the Rings films are important, the Hobbit films exponentially less so). My point is that they’re Peter Jackson films, and another director will come along and reinterpret the classic J.R.R. Tolkien novels for a new era, and in a new style. For a long while, there were only two filmed versions of Lord of the Rings, Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 adaptation of the first half of the trilogy and the Rankin-Bass 1980 TV-movie The Return of the King, which skipped to the end. And people hammered the Bakshi take hard, in part because it was pretty much all they had. The director of low-budget, often smutty animated films like Fritz the Cat (1972) and Wizards (1977) was unworthy of the material, went the common wisdom; it had too much rotoscoping (animating over live action), looked cheap, and had no ending. The Lord of the Rings is one of the bestselling books of all time, and its fans – myself included – are demanding. With the loudest voices proclaiming that Bakshi botched the film’s big screen treatment, obviously there was no Lord of the Rings: Part Two coming, and instead he returned to personal, R-rated projects, the epic immigrant story American Pop (1981) and the long-in-the-works Hey Good Lookin’ (1982). The Lord of the Rings was abandoned in a cloud of bitterness, and on subsequent TV and home video releases the closing narration was revised to imply that the Battle of Helm’s Deep really was the ending of the story, as if all the talk about Mount Doom weren’t that important.

In the Shire, Frodo (Christopher Guard) and Gandalf (William Squire) discuss the One Ring to Rule Them All.

As I write this on a laptop in my living room, framed on the wall beside me are three cels from The Lord of the Rings signed by Bakshi (the Nazgûl inside the hobbits’ room at The Prancing Pony; the Fellowship at the entrance to the Mines of Moria; Frodo and Galadriel). As the younger generation will grow up with Tolkien as defined by Peter Jackson, I knew Ralph Bakshi’s vision of Middle Earth before I was old enough to read the books. I bought the cels about fourteen years ago because the film was important to my childhood, giving me a proper introduction to fantasy and stoking my interest in Tolkien. (It was a big film for Jackson, too, as he states on the Fellowship of the Ring commentary track, and the “Proudfeet!” moment during Bilbo’s birthday speech is a loving homage to Bakshi.) I remember character-art buttons and posters being sold in stores even years after the film came out, and the Nazgûl gave me wonderful nightmares. I break out the film every couple of years and my feelings about it are always exactly the same: a lot of nostalgia, mixed with a fair appreciation of what’s good about the film and what’s not so good. But I always come to the conclusion that it’s a reflection of Ralph Bakshi, his era, and his methods. If he cut corners, it was because otherwise it wouldn’t have gotten made, and such was the case with all his films. Hand-drawn animated films are a tremendous effort of time, labor, and expense, which is why they aren’t often made anymore. What is often overlooked by Tolkien fans critical of this film is that it’s a miracle it was made at all, just like everything else in Bakshi’s filmography. He was not producing in the structured Disney studio system, but scraping together his projects with some first-rate hustling, a lot of overtime, and a group of dedicated animators who worked out of a shared passion rather than for a nice paycheck. Since this was Lord of the Rings – a book that was the Bible for many in the 60’s and 70’s – that passion from the animators is more evident than in any of his other films.

Gandalf consults Saruman the White.

They were fans and they put their best foot forward, even though, yes, in order to get the film completed Bakshi needed to film it in live action, using his Wizards technique of Xeroxing the live action onto cels. This produces a strange quality – genuinely eerie, in the Ringwraith scenes – but if not fully painted-over it simply looks like it wasn’t animated. Bakshi liked this look, but it dominates too much of Lord of the Rings, particularly in its last half hour (the Battle of Helm’s Deep). Nonetheless, it is important to note how subtle and effective the character animation truly is, when the animators were given the chance to show their stuff outside of the Xeroxing. The characters are expressive and sympathetic, especially Frodo, whose overlarge eyes and broad mouth express skepticism, brotherly love, contempt, and fear in all the right moments. Watch the scene in which Frodo shows the ring to Bilbo, tempting him: a marvel of dialogue-free emotional expression which is superior to the Jackson interpretation. Or witness the death of Boromir, which begins with shocking violence before ending quietly, as Aragorn holds him, and Gimli and Legolas slowly bow to one knee. I’m always frustrated by those who imply that rotoscoping means that no real animation has been done. Using a model for movement is not the same as tracing, and there is some very impressive and appealing animation in Lord of the Rings from a very talented group.

Legolas (Anthony Daniels), Aragorn (John Hurt), and Gimli (David Buck) witness the death of Boromir (Michael Graham Cox).

As much as this is a Bakshi film, it’s interesting to see how many of his personal trademarks are absent or reduced. This was Bakshi’s first adaptation of another person’s work, and Tolkien’s material comes first, much as capturing Frank Frazetta’s style took prominence in Fire & Ice (1983). The screenplay, by novelist Peter S. Beagle (author of The Last Unicorn) and Tolkien fan Chris Conkling, is scrupulously faithful, perhaps to a fault – maybe it would have been better if the film were faster-paced and made it through the entire trilogy, skipping over vast swaths, but that’s not the film Bakshi chose to make. What we get is all of The Fellowship of the Ring (sans Tom Bombadil and the barrow-wights, which Jackson also excised) and half of The Two Towers. There is so much plot here that it’s potentially very confusing for those unfamiliar with the novels; one major improvement in Jackson’s films is that it’s much clearer what the stakes are and who the enemy is (Sauron). A half-hearted attempt was made to clarify matters for the audience by calling Saruman “Aruman” (to differentiate his name from Sauron’s), but it only makes matters worse that he’s still called Saruman for the first half of the film! Still, there is an elegance to the early scenes in the Shire – the discussion between Gandalf and Frodo in Bag End is perfectly handled – and Frodo is placed on his quest quickly. The exposition is handled very smoothly until The Two Towers, at which point – much as in the novels – it can be challenging to understand the relationship between Rohan and Gondor, Theoden and Saruman, and so on. I tend to think the film would have been better off with just adapting Fellowship of the Ring, and smoothing over the Xeroxed animation. But Bakshi loved Tolkien, and he was ambitious.

The Balrog confronts Gandalf in the Mines of Moria.

A quality voice cast of British actors includes John Hurt (Alien) as Aragorn/Strider, Anthony Daniels (Star Wars) as Legolas, William Squire (Where Eagles Dare) as Gandalf, Christopher Guard (A Little Night Music) as Frodo, and André Morell (The Plague of the Zombies) as Elrond. You might be tested by the film’s version of Samwise Gamgee (Michael Scholes), which is a broad and grating comic relief character, in sharp contrast to Sean Astin’s nobler representation. The score by Leonard Rosenman is like comfort food to me – I own the original vinyl double-album – but I have to admit it sounds an awful lot like his other 70’s scores, including exploitation films Race with the Devil (1975) and The Car (1977). Still, Rosenman composed an original and very Tolkienesque song, “Mithrandir,” for the film’s Lothlorien sequence, and he does a fine job of establishing distinctive themes for both the Fellowship and the evil forces of Mordor. Highlights of this film include the journey into the Mines of Moria and the confrontations with the Ringwraiths, but the film stumbles as the Fellowship fractures and the action moves to Rohan. It’s flawed, but it’s a film from one of our most important animation innovators, and it’s the rare epic (132 minutes) American animated film. Even in the Peter Jackson era, there is still room to appreciate the merits of what Bakshi accomplished.