“Someone in this village is practicing witchcraft. That corpse wandering on the moors is an undead. A zombie.”

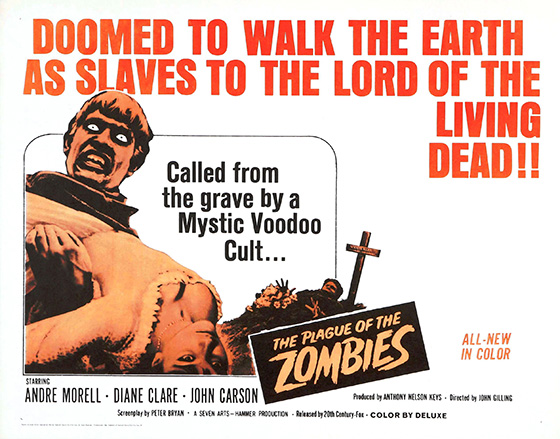

Before George A. Romero came along, zombies were all about voodoo and Haiti, and Hammer Films understood the immortal truth that there is no place more Haitian than Cornwall, England. The Plague of the Zombies (1966) was released on a sensational double-bill with Hammer’s Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966), the poster luring kids with: “BOYS! Fight back…bite back with Dracula fangs! GIRLS! Defend yourself with zombie eyes! Get yours free as you enter the theatre!” Despite the come-on, neither were kiddie flicks, but rather sophisticated adult thrillers with key shocker moments. In Terence Fisher’s Dracula: Prince of Darkness, it’s when sinister servant Klove (Philip Latham) stabs Alan Kent (Charles Tingwell), suspends him upside down over an open coffin, and slashes his throat, unleashing a geyser that resurrects Count Dracula (Christopher Lee) – this, after the mother of all pre-Ti West slow-burns. In The Plague of the Zombies, directed by John Gilling (The Scarlet Blade, The Shadow of the Cat), it’s the moment that Sir James Forbes (André Morell, The Hound of the Baskervilles) and his onetime pupil Peter Tompson (Brook Williams, Where Eagles Dare) suddenly find Peter’s dead wife Alice (Jacqueline Pearce, The Reptile) lurching about a cemetery as a zombie, and Sir James is pressed to decapitate her with a shovel. And it doesn’t let up from there. In what is later revealed as a dream, Peter confronts the dead clawing their way out of their graves, while fog pours into the grounds and Gilling’s camera sways nauseously into canted angles. He stumbles through a pool of blood, and the zombies surround him, hands wrapping about his neck…

André Morell as Sir James Forbes, the skeptical doctor who uncovers voodoo practices in a small Cornish village.

Both films are strong examples of Hammer Horror in the mid-60’s, transitioning from their classic era of the late 50’s and early 60’s (including touchstones The Curse of Frankenstein and Horror of Dracula) into the taboo-pushing age of the late 60’s and early 70’s, where they would have to fight to prove their continued value to the genre. Even in 1966, Hammer was looking a bit antiquated, grasping tightly to their trademark Gothic stylings while Roman Polanski was releasing the more groundbreaking Repulsion (1965), and on the cusp of Rosemary’s Baby (1968). But Hammer couldn’t be counted out quite yet. The first (and last) zombie film Hammer produced, The Plague of the Zombies was in part a throwback to Jacques Tourneur’s classic for Val Lewton, I Walked with a Zombie (1943), and most especially the eerie Bela Lugosi film White Zombie (1932). Morell’s Sir James Forbes and his awestruck sidekick, Peter Tompson, recall the Van Helsing/Dr. Seward dynamic in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which makes it a Hammer Gothic (the decapitation scene echoes the confrontation with the vampire Lucy in the novel). Simultaneously, the blunt violence, like that of its companion film, grant the film a necessary edginess for 1966, and it’s often been noted that the dream sequence in the cemetery has a George Romero vibe some two years before Night of the Living Dead (1968). These zombies weren’t flesh-eaters, but they certainly had bite. With their white contact lenses and decaying faces lurching suddenly into the frame, they are a stunning presence, much more so than the venomous title character of Hammer’s The Reptile, released the same year and with some of the same credentials (such as director Gilling and actress Pearce).

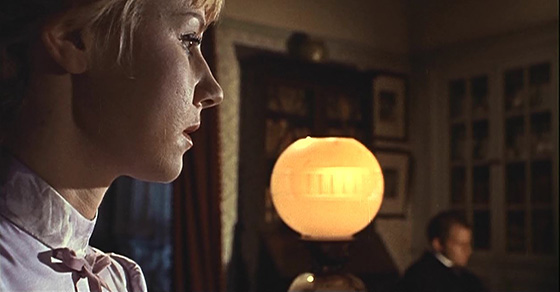

Sylvia (Diane Clare) falls under a voodoo spell.

The screenplay, by Peter Bryan (The Hound of the Baskervilles), was originally entitled The Zombie and had been kicking around the Hammer offices since 1962. It is, in many ways, a scenario assembled from the parts of other Hammer films, Frankenstein-style. Apart from the Van Helsing type and his assistant, we have a secret society of “witchcraft” (a la The Witches), grave-robbing, a fiery finale, a token part for Michael Ripper (here playing a police sergeant), and a perfect Hammer setting at the familiar Bray Studios. Most evocatively, this small Cornish village is surrounded by moors and a forest which is explicitly referenced in fairy tale terms: “Please take care not to stray on the path,” Squire Clive Hamilton (John Carson, Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter) warns Forbes’ daughter Sylvia (Diane Clare, The Haunting). Those who don’t remain in the comfort of their homes find themselves “in the woods,” or “on the moors,” and inevitably prey for Hamilton’s plot to turn the villagers into zombies for his secret mine operation. At their best, the Hammer Gothics take place in this twilight world of myth and folklore, even if The Plague of the Zombies is essentially nonsensical. Squire Hamilton has spent some time abroad, and Forbes accuses him of studying voodoo witchcraft while in Haiti – picking it up and carrying it back to England like some venereal disease. It’s somewhat redundant to point out the inherent racism of the plot, as so many of these types of stories are rooted in Colonialism. One can only wonder at the inexplicable appearance of three black men endlessly beating away at their drums in Hamilton’s mine. Did he import them from Haiti? What do they do in their off-hours? Why are they wearing Fred Flintstone lodge hats?

Alice (Jacqueline Pearce) turns zombie.

Regardless, Gilling, a master of dynamic compositions, draws out the fever-dream qualities of Bryan’s script, so that it doesn’t really matter if none of it makes any sense. While you’re watching it, it’s compelling stuff: Morell, in a most deserving starring role (he’s a Hammer MVP), alternates his delivery between the soft-spoken and something approaching a threatening growl. Cleverly, the thrust of the plot is his melting skepticism: at first he impatiently dismisses Peter’s allegations as “hocus pocus,” until he finally sees the patterns – particularly Hamilton’s method of “accidentally” cutting his victims with glass so he can steal a sample of their blood – and by the time he steps through the doors of Hamilton’s estate to confront him directly, the audience is on the edge of their seats. When Morell tangles with a dagger-wielding acolyte in Hamilton’s study, he knocks the man into the fireplace so that he catches on fire, and then stabs him with his own dagger. The exterior of the mine is a surreal jumble of mechanical gears with a towering pulley, the site of one of the film’s biggest jumps, when Sylvia discovers Alice in the hands of a zombie who cackles as he throws the corpse at her. In earlier scenes, Sylvia is tormented by the “Young Bloods,” a gang of fox-hunters in red jackets who take revenge after she leads them down the wrong trail (she sympathized with the fox). Like a modern fraternity of date-rapers, they abduct her by horseback and take her to Hamilton’s place, surrounding her with menace; when Hamilton intervenes, we have a good guess as to what horrible fate was otherwise in store for her. (“Come on little fox,” they taunt her. “Go to ground.”) Hamilton urges her to speak of this to no one, for the village would be ruined without him – an interesting statement since the village has been greatly depopulated while he conducts his zombie experiments (Forbes is led to believe this is a plague of “marsh fever”).

Lobby card depicting the film’s climax in the mine.

If ultimately The Plague of the Zombies doesn’t rise to the upper echelon of Hammer – heights that would be reached, one final time, by The Devil Rides Out in 1968 – it’s nonetheless a very solid piece of Hammer Horror, and a valiant, memorable attempt to tackle one of the few classic monsters they hadn’t gotten round to yet: a checked box in the same manner as the admittedly superior The Curse of the Werewolf (1961), the studio’s only werewolf film. It’s the product of a studio that could, at this stage, make fun, glossy genre films in its sleep. The Plague of the Zombies was one of four films shot back-to-back at Bray Studios, the others being Dracula: Prince of Darkness, Rasputin the Mad Monk, and The Reptile (all 1966), films that redressed the same sets and rotated cast members, furthering that strange continuum that suggests our current climate of “shared universe” franchises. Hammer would soon drift away from Bray, and eventually sell the studio off entirely, but for a little while the flame still burned bright under the Hammer banner.