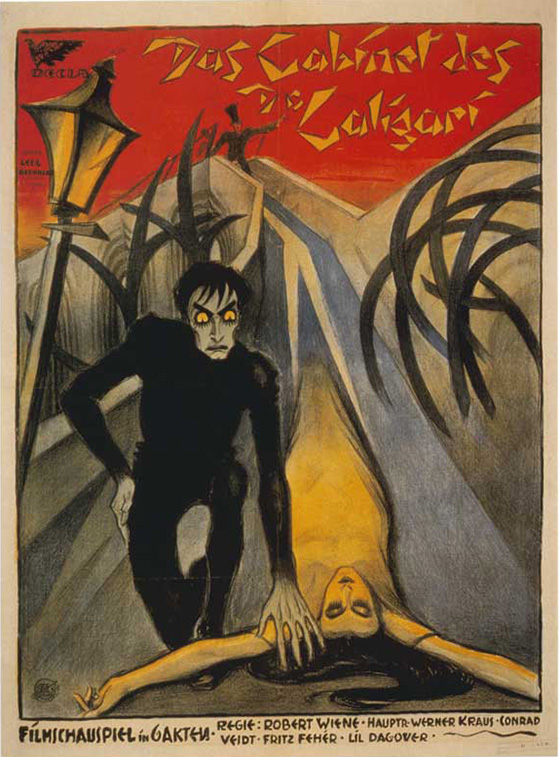

Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) is one of those rare films whose stamp has marked so much of horror, fantasy, and film noir that it hardly seems to have existed in the first place. Therefore it seems appropriate that the film is a dream within a dream. It arrives out of the fog, and by the end of the film its story has slipped back into it. You can’t quite get your fingers on Dr. Caligari, like some archetype that’s been passed on through the primeval – like Caligari himself, a figure who, we are told, was a murderous mystic from the 18th century, and who has been reborn thanks to a modern doctor at an insane asylum who wishes to resurrect Caligari’s experiments in mind controlling a somnambulist. Wiene’s nightmare of a film is framed as a story told by an inmate at that asylum, and he’s an unreliable narrator, to say the least. His tale is visualized as a funhouse of the psyche: painted shadows mark the floors, casting unnatural, angular shapes; walls and doorways are crooked, like the art of a schizophrenic; black makeup draws exaggerated lines upon the faces of the actors; and the entire village of Holstenwall is a hill of homes leaning against each other like a cat arcing its body in fright. The Expressionist method of making the psychological real – and the real nowhere in sight – would continue and flourish for a brief, wonderful period in German film, particularly in the cinema of F.W. Murnau (Nosferatu) and Fritz Lang (Metropolis). But Caligari opened the slanted door and let all the lunatics out to dance.

Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss) seeks permission to display his somnambulist in the village fair.

Could a hypnotized man do something against his constitution? Would a sleepwalker, who has been asleep his entire life, commit murder through the domineering will of another? Caligari (Werner Krauss, Waxworks) intends to prove the theory by utilizing the sleeping Cesare (Conrad Veidt, The Man Who Laughs), whom he keeps in a coffin-like “cabinet.” Setting up at the local fair in Holstenwall, he makes the outlandish claim to the spectators that Cesare’s endless sleep has given him the gift of foresight. When young Alan (Hans Heinrich von Twardowski) asks Cesare how long he has to live, the chilling response is “Till the break of dawn!” That night, he’s brutally stabbed in his bedroom. (We only see the shadow of the assassin, holding a knife as drawn and sharp as all the other shadows in the film.) It is the second murder in two nights. Alan’s friend Francis (Friedrich Feher) investigates the crime, certain that Cesare committed it under Caligari’s influence. But Cesare appears to never leave his cabinet, and when the police arrest a sociopath with a knife in hand, the case is ready to be closed. Under interrogation, the criminal claims he was only imitating the recent murders so that his own crime of passion would be blamed on the serial killer. When the police raid Caligari’s cabinet, they find he’s been storing a mannequin inside while Cesare stalks the night with a knife in hand. Caligari is chased to the insane asylum, where they discover he’s the asylum’s director, taking the pseudonym “Dr. Caligari” to recreate the experiments of the Caligari and Cesare who came before.

Back in the framing story, Francis – just another inmate – brings us into the asylum hall to prove that his story is true. And there is Cesare, pacing back and forth with a flower in his hand; there is Jane (Lil Dagover), Francis’s lover, who believes she’s a queen; and there is Caligari, who looks, for once, “normal.” Yet the set is not. The asylum remains a bizarre sight, as though the inmates had designed it themselves. The interstitial cards are still written in a stylized font upon abstract shapes. If you can’t shake the feeling that it’s all still a dream, that’s because it surely is – except, unlike The Wizard of Oz, there’s no safe settling back onto the firm ground. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari spins madly off on a raving laugh. It also sets the stage for so much that’s to come: not just more German Expressionism, but all those who have been influenced by it, from 40’s noir to Suspiria horror to Tim Burton fantasy (who modeled Edward Scissorhands on Cesare). Yet when watching Caligari on the big screen as part of the 2015 Wisconsin Film Festival, in a restored print from Kino, I noticed for the first time that so much of the famous painted sets are actually massive drop cloths, draped over everything to create its surreal world. There are wrinkles in the sky, and the ground sometimes shifts under the actors’ feet. The film seems that much more theatrical, and perhaps a bit thrown-together, but simultaneously it has become even more dream-like, with the realization that at any moment Dr. Caligari might sink straight through the pillowy ground to God knows where. The aether.