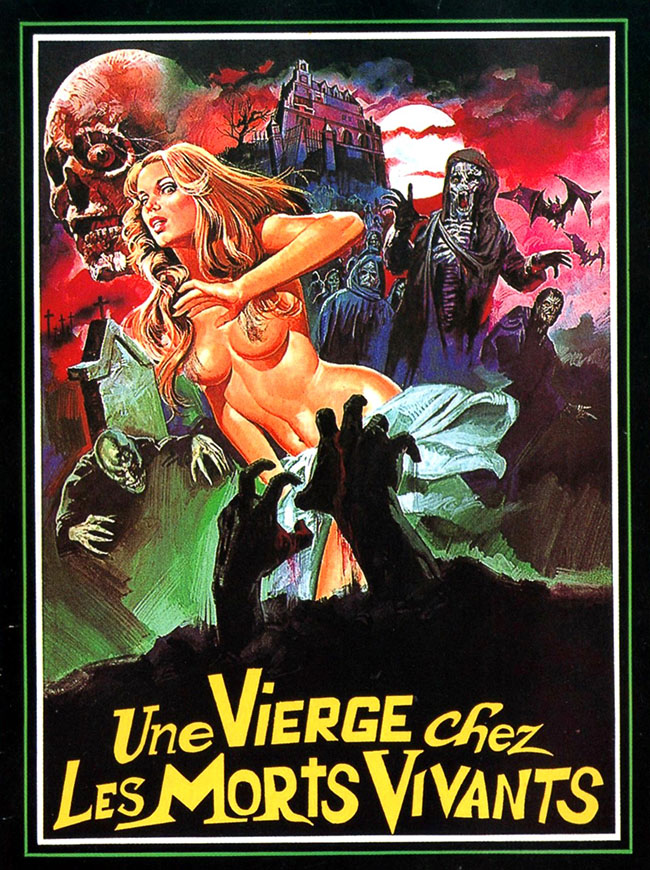

There is a subtly remarkable moment which occurs late in Jess Franco’s A Virgin Among the Living Dead (1973). Christina (Christina von Blanc, A Bell from Hell) has been navigating her way through and around a mansion belonging to her dead father and inhabited by relatives who are possibly ghosts, vampires, lunatics, or all of the above. Suddenly she encounters her father (Paul Muller, Vampyros Lesbos), a hangman’s noose about his neck, sitting in a dark room with a wooden chalice before him (the Holy Grail?). Like Hamlet’s father, he claims he was murdered, and issues a warning before the “Queen of the Night” (Anne Libert, Dracula’s Daughter) places a hand on his chest and together they slip slowly back into pitch darkness. Then Christina is in daylight, walking through the forested grounds of the mansion in the same blue nightshirt while Bruno Nicolai’s crystalline score sparkles about her, and her father appears again, suspended now from his noose, floating down the path ahead of her as he whispers, “Christina…” Clearly, this strange and hypnotic film was very personal to the director. The plot is tissue-thin (Christina returns to her family home for the reading of her father’s will), the dialogue nonsensical. More important are the images: absurd, erotic, beautiful, morbid. With its Gothic fantasy lyricism it calls to mind Jaromil Jires’ Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970), Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil (1973), and most especially the films of Jean Rollin (Shiver of the Vampires, Requiem for a Vampire, etc.). It also feels that Franco, one of the most prolific exploitation directors of the 60’s and 70’s, has cleared a space for himself to make a picture that bows to no one else, that is summoned entirely from his subconscious, that relies more upon images, music, sounds and mood. Production company Eurociné set upon it with knives. Franco wished to call the film Night of the Shooting Stars, but it became Christina, Princess of Eroticism and A Virgin Among the Living Dead. There wasn’t enough sex, so a non sequitur scene in a park, directed by someone else and featuring an orgy with a mask-clad, topless Alice Arno (La comtesse perverse) was awkwardly wedged into the film. When Dawn of the Dead brought zombies back into fashion, Eurociné even convinced Jean Rollin, fresh off Zombie Lake (1981), to shoot some zombie footage for Franco’s aged movie – as if making Zombie Lake weren’t humiliating enough. But discard the cynical additions, as Redemption has done for their Blu-Ray release of Franco’s cut of Virgin, and you will still find that unique, mournful picture which the director originally intended. It is one of his best.

Christina (Christina von Blanc) innocently explores a haunted mansion.

Christina von Blanc is radiant as the innocent Christina Benton, oblivious to the off-kilter mannerisms of the relatives that stalk the gloomy mansion of her father. “Uncle Howard” (Howard Vernon, The Diabolical Dr. Z) plays his piano and quotes the Bible for no apparent reason. Carmenze (Britt Nichols, Tombs of the Blind Dead) seduces anything that moves. Herminia, the young widow of Christina’s father, dies upon Christina’s arrival and is immediately given a mass, propped up in a chair while Uncle Howard sings Latin hymns at the piano, a cigarette in his mouth, Carmenze painting her toenails. Aunt Abigail (Rosa Palomar, Lovers of Devil’s Island) and the gibbering idiot manservant Basilio (Franco himself) are later seen with Herminia’s severed hand, carefully removing her valuable rings. “Tomorrow we will pluck out all her gold teeth!” Carmenze is seen cutting the flesh of a willing blind girl (Linda Hastreiter) and ravenously licking the bloody wounds. Meanwhile, in a dark room, the Queen of the Night sits at a desk sketching crosses in blood. Amidst all the death, decay, and greed, Christina smiles, eats breakfast, skinny dips in a lake draped with lilypads. Whenever the horror of her world confronts her directly – which often seems to be the reality, the inevitability of death – she wakes up in bed, as if everything around her might be a passing nightmare. After her skinny dip, a young stranger warns her that the mansion she’s occupying is abandoned, forbidden, haunted by ghosts. There is also the possibility, as she wakes up raving under the care of a doctor and nurse, that everything has been summoned from her fevered mind in the moments before her death.

The lake to which Christina is drawn.

The mournful atmosphere is all-pervasive, leading to a very Rollin-esque finale in which Christina’s family, standing on the lawn still as statues, attend her symbolic, ritualistic death. But Franco applies a winking humor as well, notably in the rote reading-of-the-will scene, which cuts again and again to Franco’s Basilio nodding off. (When the notary is finished, Basilio stirs and politely applauds.) Then there are the moments of I-don’t-know-what, such as when a nude Christina awakens to find a large black dildo in her room, standing upright on a barren floor. She kneels before it and slowly reaches out, then suddenly smashes it to pieces. Cut to the blind girl, who cowers in a corner and says, “What have you done? Poor soul. You shouldn’t have destroyed the great phallus. Misery is now upon us. Our time has come.” But despite the periodic flashes of eroticism, potent or offbeat, the film is more concerned with death, which gives it an eerie, oddly powerful frisson. In the audio commentary track for Redemption’s Blu-Ray, Video Watchdog‘s Tim Lucas sees a connection to the recent death of Franco’s muse, Soledad Miranda; indeed, the film feels like a elegiac meditation. It’s present in Nicolai’s haunting (and creative) score, and in the final lines – “Your mind will no longer discern the truth. You will create your own nightmares. The Queen of Darkness is here…” – as Christina slips beneath the lilypads.