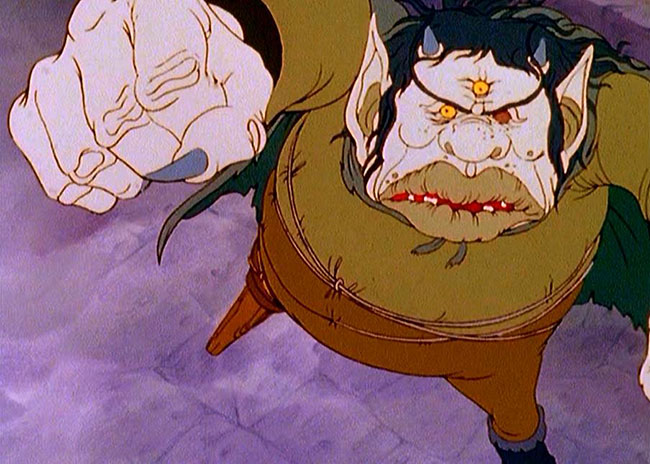

There’s a good chance that if you grew up in the 80’s and you loved fantasy, you remember The Flight of Dragons (1982). For years, my memory was extremely selective – I recalled an early scene set in a bookstore in which the main character plays a “Flight of Dragons” prototype board game with the shopkeeper, and I remembered the last half hour, which involves battles with various monsters. I remembered those scenes because they encapsulated the appeal to a child obsessed with fantasy: the Dungeons & Dragons elements, basically. (Not that I was allowed to play Dungeons & Dragons, because my mother thought it was a cult. The 80’s also brought us that hysteria, and for more information I would point you to the early Tom Hanks film Mazes & Monsters, which is the Reefer Madness of D&D.) What I did not remember was the fact that the film is mostly expository set-up, and it’s only the last half-hour when it actually gets going. What I did not remember were the endless scenes of scientific explanation for dragon flight, dragon fire, and so on; nor the theme of science vs. magic which is not so much a subtext but as upfront and face-scorching as dragon’s breath. In recent years I’ve watched the film a couple of times, driven by nostalgia, but there must also be an element of masochism, for my eyes glaze over until that last half hour finally comes, and our laboriously-assembled band approaches the “Realm of the Red Death” to battle a three-eyed ogre, a worm bathing in acid, an army of dragons, and an evil sorcerer voiced by James Earl Jones. So let’s face it, The Flight of Dragons is a bit of a slog. But it’s also unique and odd, to the point that I am still not sure exactly why it exists.

The wizard Carolinus (Harry Morgan) introduces himself to Peter Dickenson (John Ritter) – based on “Flight of Dragons” author Peter Dickinson.

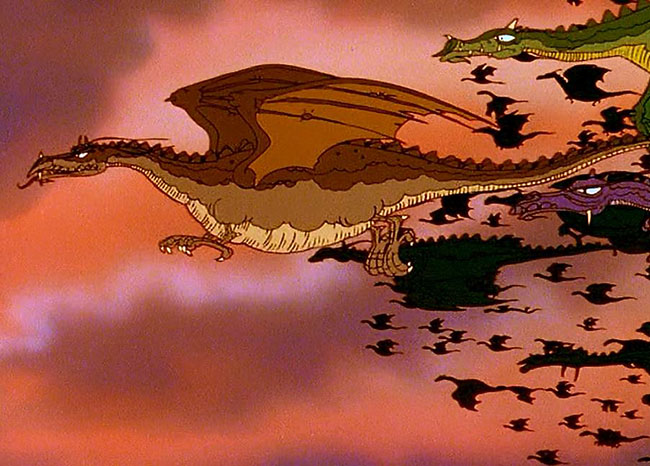

The plot involves a “man of science” – who is also an aspiring fantasy author – transported from modern-day Boston to a medieval fantasy world where he becomes trapped in the body of a dragon. The film is just as unlikely a hybrid. For one thing, it was a collaboration of American animation studio Rankin-Bass with the Japanese studio Topcraft. Topcraft’s best known film is Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), and the studio would soon become the celebrated Studio Ghibli. Topcraft and Rankin-Bass collaborated on many animated productions, most notably The Hobbit (1977), The Return of the King (1980), and the feature film The Last Unicorn (1982). Though released the same year, in many ways The Flight of Dragons feels like a test run for The Last Unicorn. But Flight was also a hybrid adaptation of two different books: the title is drawn from British author Peter Dickinson’s 1979 book, but some of the plot (a man’s consciousness inserted into a dragon’s body) is taken from Gordon R. Dickson’s The Dragon and the George (1976), the first in his Dragon Knight series of novels. This combination is a little odd, not the least because Dickinson’s book isn’t a novel at all, but a discursive coffee table book arguing for the historical existence of dragons. Dickinson takes as his premise that dragons were real, so his essay, illustrated by Wayne Anderson, goes to great lengths to justify dragon chemistry (the fire-breathing), aerodynamics, and dietary habits (well-born maidens), all the while treating fictional accounts – including Dickson’s The Dragon and the George – as factual. Fantasy was flourishing in the 70’s and early 80’s, and the Flight of Dragons book was of a piece with other coffee table art books exploring the life cycles of mythological creatures, including Gnomes (1976), Faeries (1979 – by Brian Froud and Alan Lee), and Giants (1985). Gnomes, the Dutch-imported phenomenon, eventually led to a 1980 TV-movie, and Faeries became a half-hour special in 1981, so maybe this is why Rankin-Bass targeted The Flight of Dragons for a 90-minute television film, with a title song crooned by Don McLean of “American Pie” fame.

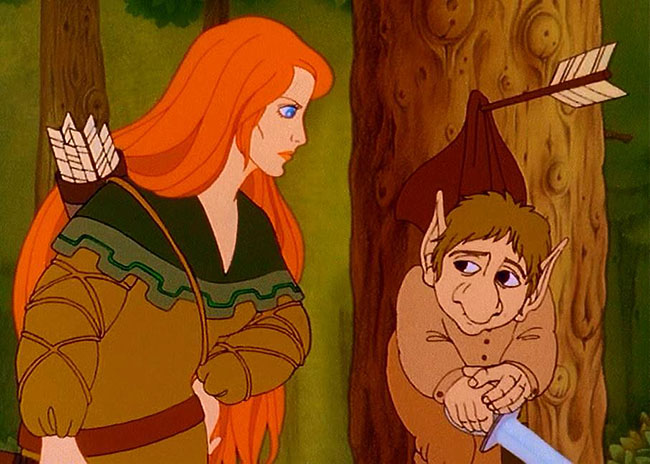

The archer Danielle discovers a wood-elf, Giles.

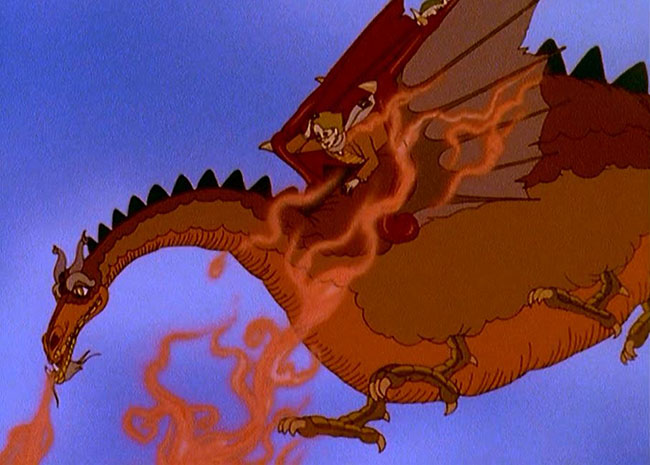

But a dry explanation of a dragon’s use of hydrogen in flight doesn’t quite sustain a feature length story, so The Dragon and the George forms a rough outline of a plot. No worries, we get plenty of Dickinson’s pseudo-science in the first half of the film, imported from his book and delivered by none other than Dickinson himself – well, as voiced by John Ritter. Ritter’s “Peter Dickenson” (as it’s spelled in the film) is now an American scientist longing to write a Flight of Dragons book, but can’t find the time, so he’s made a board game instead. When he’s teleported by the good wizard Carolinus (Harry Morgan of M*A*S*H) into a magical realm, his firsthand experiences with dragons will give him all the knowledge he needs to finally complete his book. Accidentally merged with the “house dragon” Gorbash, he embarks on a quest to retrieve the red crown, the source of power for Ommadon (James Earl Jones), who wishes to destroy all technology with magic and an army of mind-controlled dragons. (At one point, Jones chants “Doom, doom, doom, doom,” as though cross-promoting the same year’s Conan the Barbarian.) Peter has been chosen because he is a man of science, and only science can thwart magic. In his quest he’s joined by some fairly typical fantasy tropes including a wise, elderly mentor (a dragon), a valiant knight, a red-headed female archer, a talking wolf and a wood-elf. Princess Melisande is the love interest, but she remains at home with Carolinus throughout the quest, which means one potential source of drama and character development is briefly teased and abruptly removed. Surprisingly, many of the characters die; unsurprisingly, most of them are resurrected when evil is defeated.

A three-eyed ogre must be overcome to enter the evil wizard’s lands.

The animation is good, even if the styles are jarringly varied. Wayne Anderson, illustrator of the original book, receives a credit for design, and his influence is clear in the dragons, as well as many of the background paintings. Other characters, such as the princess with her large, quivering eyes, seem to have stepped in from one of Topcraft’s anime films, and the wood-elf Giles looks just like a Rankin-Bass hobbit. More intriguing is a brief glimpse of the realm occupied by the wizard Lo Tae Zhao – his is a traditional Chinese dragon, and his mountaintop castle is built of pagodas. The theme of science vs. magic had been previously explored in a much edgier animated film, Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards (1977), but this family-friendly treatment spells out its themes gently – and repeatedly. It’s Peter’s science and logic which defeats sorcery, but it also expels Peter from the realm, sending him back to Boston. (“I deny all magic!” he shouts.) Carolinus is wistful that the days of magic are coming to an end – technology is inevitable. His plan is to remove all magic to one safe haven where it can live undisturbed while time marches on. It’s a pragmatic message for a children’s movie: science is more important than fantasy, but fantasy has its place. Yet somehow it still didn’t fully connect, because all I ever remembered were the monsters and the dragons.