I wanted to follow up my review of Excalibur (1981) with Dragonslayer (1981), not just because it’s another sword & sorcery film released the same year, but because it’s trying to do much the same thing thematically, albeit with a much simpler story. Like John Boorman’s Arthurian epic, Dragonslayer is about a transition from the “Dark Ages,” with its magic and mystery, to modernity and the rise of Christianity. In both films, the past is represented as being the time of dragons: in the case of Excalibur, “The Dragon,” referenced many times as the sort of nature-energy that unites everything, and to which Merlin and Arthur are uniquely in tune. And in both films, the dragon is dying, and organized religion is taking its place. As Gawain discovers the Holy Grail, he also sees a vision of Arthur as Christ, and declares his worship of him. (Yes, Excalibur is a pretty strange movie.) In Dragonslayer, the fall of the dragon is associated with the rise of the Church – or, as one character puts it, “Isn’t it strange that the very moment that the beast was put down there should be a holy man in the village?” That character, Greil (Albert Salmi, Escape from the Planet of the Apes) is baptizing the desperate “Urlanders” by the climax of the film – this, after the visiting priest was reduced to ash by the dragon, which possesses the most wonderful of names, Vermithrax Pejorative. That priest’s death is the film’s homage to George Pal’s War of the Worlds (1953) – not even God can save these men, and it’s magic which ultimately destroys this very magical creature. But the dragon is the last of her kind, like Smaug in The Hobbit, and described as old, “pitiful and spiteful.” Once she has passed, so passes an age.

Galen (Peter MacNicol), the sorcerer’s apprentice.

The one who devises the plot which ultimately slays the dragon is Ulrich (Ralph Richardson, who played God in the same year’s Time Bandits). Ulrich is an old sorcerer, and he, like Vermithrax, is in his autumn years. In fact, he appears to die in the film’s opening minutes; accepting the challenge to prove his magical prowess by a test, he allows the king’s champion Tyrian (John Hallam, Flash Gordon) to plunge a dagger through him. This leaves the fate of Urland in the hands of his young apprentice, Galen (Peter MacNicol, Ghostbusters II) and a girl disguising herself as a boy, Valerian (Caitlin Clarke). But Ulrich is playing the long con, as we learn in the film’s final act, and in his greatest trick of all, he slays Vermithrax and himself (with Galen’s help), thus ending the time of magic with a fiery explosion, and allowing the modern world to replace it. The king (Peter Eyre, Mahler) poses over the dragon’s corpse with a sword in hand, like a St. George – and steals the credit. Galen and Valerian are left with nothing but a horse to ride into the sunset. There isn’t room for their kind anymore. But it’s interesting that director Matthew Robbins (*batteries not included), who co-wrote the film with his Sugarland Express screenwriting partner Hal Barwood, treats his magicians like modern-day illusionists and con artists, with just enough self-taught, authentic, primal magic. To introduce Ulrich to his visitors, Galen plays the drums ominously and manipulates a sheet of metal to sound like thunder, as though he were running the sound effects on a radio play. During a festival, he’s seen playing a shell game with a child. And when he presents his mighty powers to the king, he’s like a low-rent David Copperfield, and apologizes to his bored audience when he fails to levitate a table. Usually when this film is brought up, the casting of prolific character actor Peter MacNicol as the hero is criticized; perhaps it’s just because I’ve known this film since my parents rented it on laserdisc when I was a child, but I’ve never had a problem with him. He’s not supposed to look like the traditional hero. He is awkward and bumbling, full of vanity and pride; but he has just enough curiosity and bravery to save the day. It is a bit off to have a medieval European fantasy whose two central roles are played by Americans: MacNicol is a Texan by birth, and Caitlin Clarke (who, sadly, passed away in 2004) was born in Pittsburgh. But they play their roles with conviction, so it’s not as distracting as it might be. Neither of them are as out of place as a Kevin Costner Robin Hood, I’d argue. Only when Valerian has to express her love for Galen does Clarke stumble, but that has more to do with the film’s utter inattention to their love story. Dragonslayer is more concerned with other things. For example, how incredibly awesome that dragon is.

A virgin Urlander (Yolande Palfrey) is sacrificed to the dragon Vermithrax.

And Vermithrax does bring the awe. Robbins is smart to keep the dragon off-screen for most of the film, building his presence much as his mentor Steven Spielberg did with the shark of Jaws. First we see one of the many virgin sacrifices which Urland maintains to satisfy the dragon and keep her from burning their villages. A young girl is bound by manacles to a pole with dragon carvings at the top, and the ground rumbles and steam hisses from the rocks as she struggles to loose her bloody wrists from the irons. We see its tail and its claws, but we don’t see the dragon’s head when it rises above her – just the girl from the dragon’s point of view, smaller and smaller as the neck extends, and then the screen is bathed in flames. When Valerian explores the dragon’s lair, she encounters one of its young, lunging at her with a squeal before the smash cut to the next scene. Much later, when Galen discovers the Lake of Fire where the hellish creature lurks, we see its outline looming behind him before he catches a reflection in the waters; and then he turns and Vermithrax is revealed spreading her wings – inhaling deep, chest puffing up, as we can feel all the oxygen drawing out of the room. Then comes the blast as Galen lifts his shield. Vermithrax is an astronishing creation, a stop-motion puppet designed by Phil Tippett (Jurassic Park) at Industrial Light & Magic. Technically it is Go Motion, a tweaking of the old Willis O’Brien/Ray Harryhausen technique by adding a more realistic blurring to the model’s motion. He previously used the method for the Imperial AT-AT Walkers in The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Even all these years later, Vermithrax looks really damn good. For one thing, she is really there – the same night I watched Dragonslayer, I watched an episode of Game of Thrones, and as much as I enjoyed the sight of dragons guarding Daenerys Targaryen, they did not look physically present. Vermithrax looks real, because she is real. The seams only show when this miniature puppet must be matted into the background. For example, you might not notice that when Vermithrax shoots fire at Galen in the Lake of Fire, the neck doesn’t convincingly merge with the water. That’s because your eyes aren’t going to that spot – understandably. Put simply, Dragonslayer is one of the best-looking FX pictures of the 80’s, and still holds up admirably today. But it is more than just an FX picture. It is beautifully shot, for one thing: Matthew Robbins hasn’t made very many films (though he’s written the upcoming Guillermo del Toro thriller, Crimson Peak), but along with his director of photography, the late Derek Vanlint (Alien), he has made a fantasy film that is one of the best-looking of its era. The forest glades are green and lush; the mountains and villages mist-shrouded and forbidding; the dragon’s lair the stuff of nightmares, littered with bones and the mutilated corpse of a princess, feasted upon by baby dragons (in a scene usually cut for the TV showings).

Galen witness the resurrection of Ulrich (Ralph Richardson).

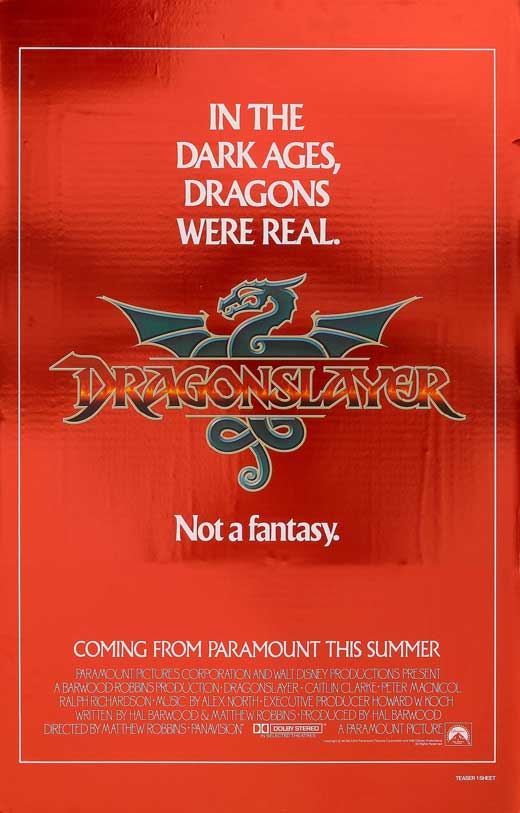

The grittiness is surprising, because this is a Disney co-production with Paramount Pictures. For a Disney film, the mutilated princess is downright shocking. There’s even some brief nudity when MacNicol goes skinny dipping with Clarke. But most of all the film is terrifying for youngsters (I can attest – as a child I was terrified, and loving it). The deaths of the virgins and the priest are played to maximum horror-movie effect. The score by Alex North (Cleopatra, Spartacus) is atonal at times, Viking-like, but often simply ominous, enough to instill discomfort or dread. Refreshingly, North doesn’t try to impersonate John Williams in Star Wars or Superman mode – as most fantasy scores of this era did, to sometimes grating effect. So the film has integrity; about the only time the Disney roots are evident is when Ulrich stands atop a mountain, late in the film, and commands the heavens, like Mickey in Fantasia – the original sorcerer’s apprentice. Actually, perhaps Disney was too concerned the film might be thought of as another children’s film – the poster, self-consciously, proclaimed “Not a Fantasy.” But of course it’s a fantasy. A brilliant one.