“Should any of my readers incline to a serious study of the subject, and thus come into contact with a man or woman of Power, I feel that it is only right to urge them, most strongly, to refrain from being drawn into the practice of the Secret Art in any way. My own observations have led me to an absolute conviction that to do so would bring them into dangers of a very real and concrete nature.” -Dennis Wheatley’s “Author’s Note,” The Devil Rides Out (1934)

“…In practically everyone I meet – I think in everyone – the ultimate triumph of the power of good over the power of evil comes about…I think it’s a truism of experience that we will find, in the end, the ultimate, inevitable triumph of good over evil.” -Terence Fisher, director of The Devil Rides Out (1968), interviewed by Harry Ringel in Cinefantastique Vol. 4 No. 3 (1975)

“I finished The Devil Rides Out about two weeks ago, after five extremely unpleasant nights in the rain and damp in the woods near Pinewood Studios…I have high hopes for this film, and it will prove, once and for all, that I can be accepted in a completely normal role.” -Christopher Lee in his fan club letter, as quoted in The Hammer Story by Marcus Hearn & Alan Barnes

When Christopher Lee’s death at the age of 93 was announced this week, the outpouring of tributes was ubiquitous. If you didn’t know him as the star of Hammer horror, you recognized him from something: perhaps as the wizard Saruman from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003) – a role the actor, who had met J.R.R. Tolkien, truly relished – or perhaps as the sharpshooter Scaramanga in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). A co-worker of mine knew him principally from his heavy metal albums (!). But Lee, of course, made his name with Hammer, from his breakthrough roles as the monsters of The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Dracula (1958), and The Mummy (1959), through his series of Dracula sequels in the late 60’s and early 70’s, and finally the adaptation of Dennis Wheatley’s novel To The Devil a Daughter (1976). (When Hammer was revived in recent years, he took a small part in the company’s otherwise forgettable thriller The Resident.) Hammer adapted Wheatley’s novels three times, but the most notable remains The Devil Rides Out (1968), with Lee playing the role of the Duc de Richleau, the author’s wealthy aristocrat working tirelessly to exterminate the forces of black magic. It’s not saying much to claim that it’s the best of the trilogy of Wheatley adaptations: the other one is The Lost Continent (1968), which can be enjoyed strictly for its camp value. But The Devil Rides Out is also the best horror film Hammer ever made. Yes, I rank it higher than Dracula.

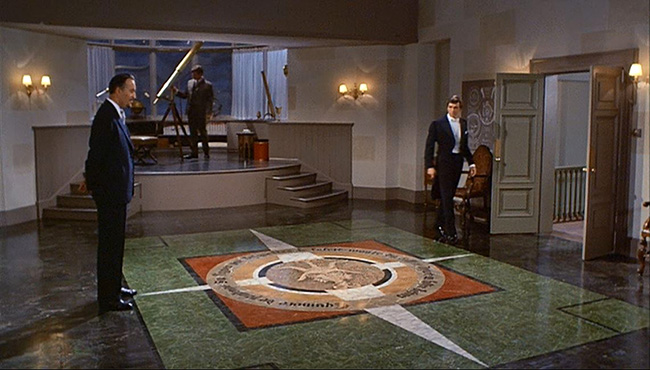

The Duc de Richleau (Christopher Lee) and Rex Van Ryn (Leon Greene) confront their friend Simon (Patrick Mower) over his involvement with the occult.

Lee was also quite fond of the film. A friend of Wheatley’s, he was only too happy to take the role of Richleau. It’s a Van Helsing-type that Hammer would typically give to Peter Cushing, and in at least one way Cushing would have been more appropriate: he was older than Lee, and Richleau is supposed to be old enough that Sarah Lawson (only six years Lee’s junior) could play his niece. On the commentary track of the DVD from 2000, he suggested a remake would be appropriate, now that he was old enough to embody the character. But Lee always had a gravitas that made him seem older than his years, and it is refreshing to see him cast as the hero, albeit a very somber and commanding one. He rankled against the typecasting that had plagued him, and avoided playing Dracula for eight years before finally acquiescing to the film’s second sequel, Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966). As with that film, The Devil Rides Out reunites the Dracula team of Lee, director Terence Fisher, and composer James Bernard. Dracula: Prince of Darkness is a classy, creepy film and a respectable entry in the series, but with The Devil Rides Out it feels like these old hands have been reinvigorated. It’s a new story and a new concept: the villain this time is none other than Satan. (Excuse me: “The Goat of Mendes – the Devil himself!”) Everyone brings their best, and in particular their conviction for the material. This is important because, unlike a typical Hammer horror film, the menace is often invisible. Sure, the antagonist is the Satanic priest Mocata (Charles Gray of You Only Live Twice and Diamonds are Forever, never better). But he doesn’t attack directly. He hypnotizes his victims, and when confronted, he smiles smugly and threatens with all the forces of the unknown. “I shall not be back,” he says at one point, “but something will.”

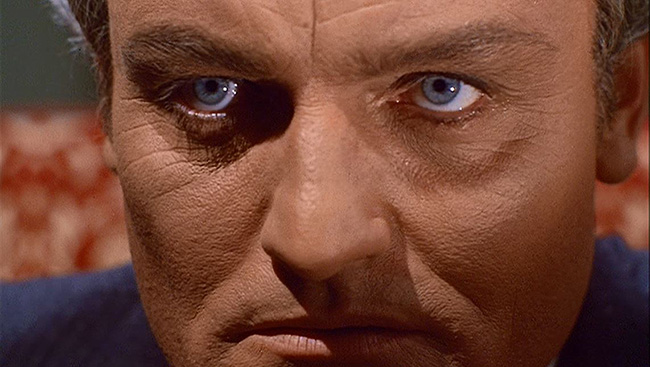

Charles Gray as Mocata.

For this sort of film, 1968 was just right and far too late. It was the year of Rosemary’s Baby – Roman Polanski’s envelope-pushing Ira Levin adaptation, so unsettling, so good, that it sparked a run of devil-themed horror that would only gain greater momentum with The Exorcist (1973). So in a sense The Devil Rides Out was ahead of the curve, part of the opening salvo of Satanic horror movies. But in style and approach it was vintage Hammer of the late 50’s/early 60’s variety. Polanski insisted upon realism throughout Rosemary’s Baby – from the location shooting at the Dakota apartment building in Manhattan, to Mia Farrow’s timid line delivery, and to the believable portrait of a young marriage hitting the rocks during a difficult pregnancy – which gives the film so much of its power. The Devil Rides Out, on the other hand, is set in the 1920’s English countryside, and features Christopher Lee’s theatrical declarations about the dangers of black magic, risking the snickers of younger audiences. One film is haunted by Krzysztof Komeda’s subtly tragic lullaby; the other is dominated by James Bernard’s full-volume orchestral histrionics. Which is all to say that Hammer’s old school version of The Devil was indeed Riding Out, and toward the sunset. But if the film can be seen as a send-off to the Hammer of the past – with a more exploitative brand ahead of them – then it’s a grand one.

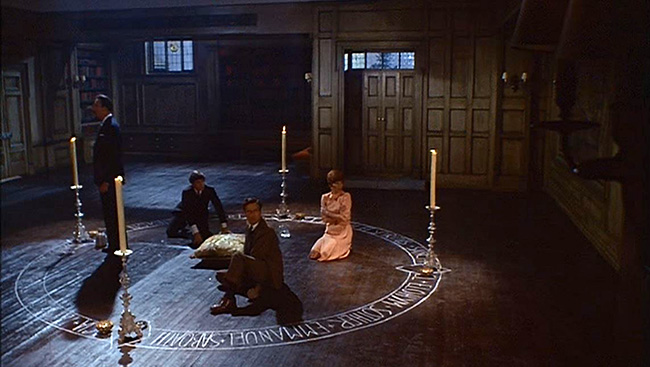

Spending a long night under the protection of a magic circle: Lee, Mower, Paul Eddington and Sarah Lawson.

The film wastes no time introducing its characters. Audaciously, it assumes you don’t need any background on them at all, so it might cut right to the action. All we know is that the Duc de Richleau is very wealthy, and when his friend Rex Van Ryn (Leon Greene, A Challenge for Robin Hood) flies in, they expect to meet the third and youngest member of their group, Simon Aron (Patrick Mower, Cry of the Banshee). Instead they find Simon hosting a private dinner party with an international group of guests, strict upon holding their number at thirteen, and calling themselves a “Circle.” Among them is the beautiful Tanith Carlisle (Nike Arrighi, Women in Love) and the silver-haired and lantern-jawed Mocata, who acts as their leader. Fisher is brilliant at widescreen staging. Watch the scene in which Lee mingles among the guests, nonchalantly smoking while eavesdropping on one conversation after another. We are focused on Lee’s Sherlock Holmes-ian guile, and listening intently to the fragments of dialogue that he overhears, while at one corner of the screen a concerned Mocata appears, and begins drifting after him. The Duc uncovers signs of the occult in an upstairs observatory, and when he and Rex sneak back into the estate after dark, they confront a demon summoned above the image of a goat in the marble floor. The next day they begin to wage their war of wills against Mocata and his circle of Satanists, intervening in the black magic baptism of Simon and Tanith at a Sabbat held in the woods, and where the goat-headed Devil is conjured following a clothed, PG-rated orgy. (If the film were made a couple of years later, the orgy would be the film’s chief point of exploitation.)

Mocata summons the Goat of Mendes.

The Sabbat is one of three showstopping scenes in The Devil Rides Out; your typical Hammer film would be lucky to contain more than one – in fact, an occult ritual would typically be the climax, as in Hammer’s (very good) The Witches (1966). The second tour-de-force moment is Mocata’s visit to the house of the Eatons, Marie (Lawson) and Richard (Paul Eddington, The Prisoner), who are sheltering Simon and Tanith while de Richleau is away. The Satanic priest connives his way into her home, and as the two politely address one another in a downstairs room – Marie stroking the hair of a doll, a very peculiar nervous habit – Mocata begins to mesmerize her. Fisher opens the scene with deliberately mundane angles, as though filming for a television drama. Then his angles become tighter and tighter, as Mocata presses his will upon Marie. Finally, his face fills the screen. Marie stares helplessly back at him. We might notice that Gray’s eyes are the same pale blue as Lawson’s: Fisher has certainly noticed, emphasizing her complete possession as she has now become Mocata’s doll. Then the camera is above Mocata’s head, and he lifts his gaze toward the ceiling. Any film class will tell you this is an angle to emphasize a character’s powerlessness. Fisher inverts it (his Satanist sneers at God). Mocata is turning his attack upward – we know the two that he wants are sleeping upstairs – and so it’s a moment of audience dread. Bernard’s score becomes fevered as Fisher cuts to Tanith, rising from her bed as Mocata’s puppet, and reaching for a knife to assault the dozing Rex.

Nike Arrighi as Tanith Carlisle.

And then, of course, there is the film’s most iconic moment, the long night spent in a magic circle while Mocata’s magic lays siege against de Richleau, Simon, Marie, and Richard. I’ve neglected to mention that the screenplay is by Richard Matheson, and this moment, more than any other, shows the signs of its author. It builds a suffocating tension out of very little, like Matheson’s best Twilight Zone teleplays, or his 1971 novel Hell House. Mocata is not present during the assault. Throughout this sequence, Fisher never shows us the sorcerer in his home, or out in the woods conducting dark rites. We are in the circle with Christopher Lee, listening to his warnings to never step outside it, no matter how much we’re tempted. Marie and Richard’s daughter appears to be threatened by a giant spider, and the Angel of Death is summoned, skull-faced and storming into the room upon a winged horse. Admittedly, the special effects – particularly of the spider – are unconvincing, and it’s more unnerving when we can’t see anything at all, such as when Rex’s disembodied voice comes from the door, then fades eerily away. (A recent Blu-Ray release in the U.K. added new digital effects, but why? It’s a film from 1968 – let it be what it is.) I’m always scratching my head as to why the daughter was left on her own, perfectly vulnerable, instead of being allowed into the magic circle from the start. Still, the scene works gangbusters, and it’s inevitable that the film’s actual climax is nowhere near as exciting – though it does once more feature the alarming endangerment of a child, as Mocata threatens to sacrifice the little girl. The Devil Rides Out is a breathless movie, propelled by a re-energized director and fronted by a Christopher Lee, who – rare in the late 60’s – was enthusiastic about his work in a Hammer movie, and committed. It’s a shame there were no further adventures of the Duc de Richleau, but it is also difficult to conceive of this kind of old-fashioned horror continuing for much longer as the 70’s loomed and censorship loosened (a notable exception being 1974’s Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell). With Lee’s passing, many are noting the many iconic villains and monsters he played over his long career; but The Devil Rides Out proved he could also excel as the lead, sending evil back into the night with a flung crucifix of his own.