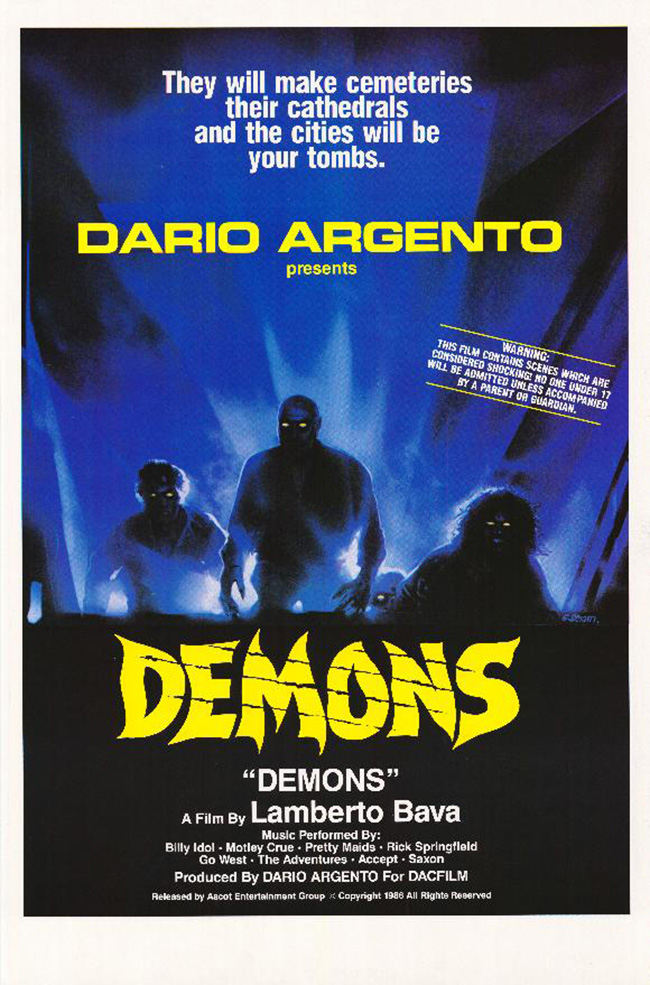

Demons (1985) posits that going to a horror film is not a safe experience. That dread you feel – and now I’m directly addressing Italian teenagers going on a date, prepared to hold each other in fear or just make out in the seats, and badly dubbed at that – that tingle of anxiety you feel, badly dubbed teenagers, is rooted in a real threat. The movie might actually attack you. The movie might possess you, and make you grow long claws and send your eyes glowing and green bile oozing out of your mouth. This is a meta horror movie, though it doesn’t get much deeper than that. The rest is cinematography and style. Director Lamberto Bava is the son of Mario Bava, godfather of Italian horror (we should politely ignore that Lamberto Bava was fresh off 1984’s Monster Shark, aka Devil Fish, rightly skewered on Mystery Science Theater 3000). Perhaps even more significantly, the producer and co-writer is Dario Argento, and the film bears his mark, with its Suspiria color scheme (cool blues and deep reds), silly and perfunctory dialogue, elaborate setpieces, and a plot that relies upon dream logic – and so doesn’t bear close scrutiny. Argento apprentice Michele Soavi, himself an enormously talented horror director (Dellamorte Dellamore/Cemetery Man, The Church, Stage Fright), acted as assistant director, has a screenplay credit, and appears in the important role as the Man in the Mask. The score is by Claudio Simonetti of Goblin. So Demons has a strong pedigree, and in some ways it plays as a Greatest Hits of 80’s Italian horror. It’s also utterly ridiculous, but that’s to be expected.

Michele Soavi as the Man in the Mask, handing out free passes to a mysterious movie screening.

As with Suspiria (1977), Demons opens with a young woman (Natasha Hovey) taking an urban trip into a metaphorical black forest, fraught with phantoms (an inexplicable masked face glimpsed in the darkness of a subway train’s window) and ominous synthesizer music. The masked face belongs to a stranger (Soavi) who, judging by the jump-scare editing, can teleport to anywhere is scariest. He’s handing out free passes to an anonymous film screening at an old movie house in Berlin. The girl, Cheryl, asks for an extra pass for her friend Kathy (Paola Cozzo). The theater, as seen in exteriors (the Metropol theater in Berlin, built in 1906), is a formidable fortress, and Cheryl, Kathy, and various other theatergoers, including a blind man, a pimp, and his two hookers, will spend the rest of the film fighting for their lives within its walls. In the lobby a motorcycle and samurai sword are on display, apparently just so they can be used in the climax. Posters are glimpsed for Herzog’s Nosferatu (1979), Argento’s giallo Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971), and the forgotten all-star concert movie No Nukes (1980). The movie-within-a-movie is along the lines of The Evil Dead (1981), with teenagers discovering the tomb of Nostradamus and reading lines which immediately cause demonic possession (as Nostradamus predicted). The first sign of possession is a cut on the face, and as a character in the film notices the symptom, a woman in the audience finds that she’s bleeding on her cheek. She inspects her face in a bathroom mirror, and it spouts pus like a geyser. Then come the claws and the green, mouth-filling goo. As the possession spreads and demons stalk the hallways and projection booth, the audience barricades itself into the theater balcony.

A demon emerges from a victim’s corpse.

Apart from the Suspiria and Inferno color schemes (strikingly shot by cinematographer Gianlorenzo Battaglia), both The Evil Dead and George Romero’s zombie trilogy are the film’s obvious touchstones: the characters are under a Romero-like siege, and the possessed like to spring up with claws extended and eyes glowing, a la Sam Raimi’s film. It’s also as gory as the genre now required, with eyes gouged and flesh shredded. When I first saw this film on VHS in the 90’s, I was captivated by the claustrophobic, nightmarish feel of the movie and its rich colors – but I hadn’t yet seen Suspiria, which did it all before, and to superior effect. This revisit was a bit disappointing – the characters are truly grating, though the unintentionally funny dialogue helps – but I am still impressed by the film’s theater-bound setting and its Argento-ized style. Most memorable is the climax, which discards all reason and features a young stud driving over the theater seats on a motorcycle, hacking at zombie-like demons with the sword, before a helicopter crashes through the ceiling…which proceeds to hack everyone up some more with its rotor blades. The soundtrack features Mötley Crüe, Rick Springfield, Saxon, and others, plus perhaps the greatest use of Billy Idol’s “White Wedding” ever, as thugs snort cocaine out of a Coca-Cola can, then spill it all over themselves. The coda becomes apocalyptic – the survivors emerge from the theater to discover that demons have destroyed Berlin, and they join up with rebels – including a gun-toting child – who act as though the apocalypse has been going on for months. By this point in Demons, you’ll have learned to just go with it.