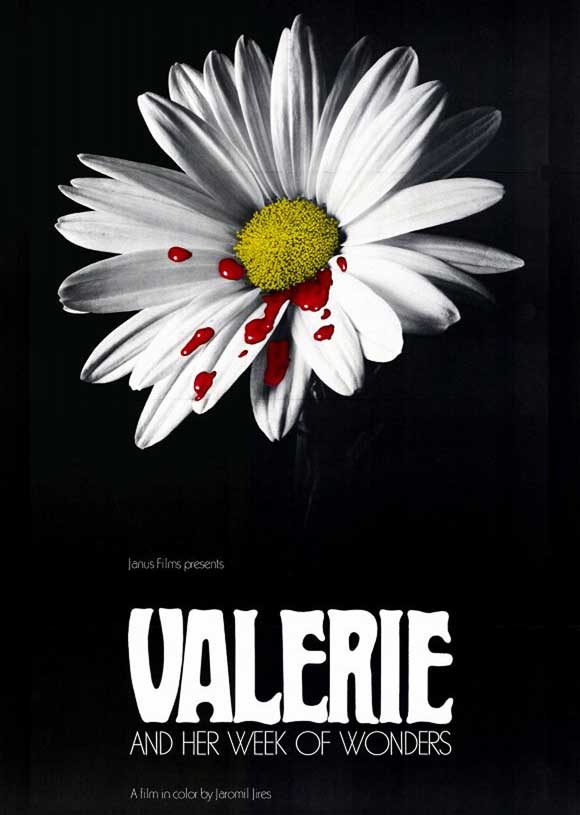

“Is there some secret in these earrings?” asks Valerie, dangling them in front of her over breakfast. She has long brown hair, so long that it becomes almost a secondary character in the film, splaying about her while she lies in a white bed in a white room, dreaming; or as she makes a mustache for herself while being burned at the stake as a witch. The earrings keep coming back, too, trading hands, envied by a monstrous, vampiric figure which she calls the Polecat, who may or may not be her father. Like a pearl necklace which her fanged cousin Elsa drapes around her sleeping head, they seem to be symbols of adult sexuality. Because more than anything else, the Czechoslovakian film Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970) is about Valerie’s passage out of childhood, from the moment she accidentally drips menstrual blood on daisies, to later in the film when she walks through the town square plucking petals off daisies in a variation of He Loves Me/He Loves Me Not, the blood still fresh on them.

Valerie (Jaroslava Schallerová) is tied to a stake by the villagers.

Adapted from the 1945 novel by Vítězslav Nezval, the film is part of the Czech New Wave of the late 60’s and early 70’s, but it’s also clearly influenced by the Surrealists, and fits snugly alongside director Jaromil Jires’ contemporary, Luis Buñuel. Refreshingly, the film’s Surrealism doesn’t feel academic or obscurely intellectual, but earthy and erotic, persuasively following its own internal logic to its natural endpoint, as dreams do. There are chickens (and chicken feathers) everywhere. The Polecat – or weasel – hunts among the chickens, slaughtering them casually. He’s a vampire with makeup reminiscent of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu – tall ears, skull-like features, hideous teeth – but he’s also “The Plague” (a la Werner Herzog’s later take on Nosferatu), and he’s a Catholic bishop, and he’s a seducer of women. He stalks about the town with a frightening weasel mask, coquettishly flaunts a purple fan, wears white gloves like an orchestra conductor and the black robe and wide-brimmed hat of a cleric, and carries a tail-wagging white Maltese at his belly. Sometimes he cracks a whip, much like a number of shirtless men who chase Valerie throughout the village, whipping, whipping. Her grandmother is pale as a corpse and lusts after the Polecat, seeking the gift of youth. And Valerie flaunts her youth among all the corpses and chicken-filled coffins, skipping, smiling, swimming in the fountain with her hair floating around her. She lives in a house with chicken coops in the attic and a vampire’s crypt in the basement. She’s well suited to dance between both worlds, as a perverted priest attempts to ravish her, as she witnesses dark visions of a wedding, as she accepts the kisses of a handsome young missionary named Eaglet, who resembles The Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian, who plays instruments that can conjure any kind of music, and who may or may not be her long-lost brother.

The Polecat (Jirí Prýmek)

All of these elements swim around each other like Valerie drifting in circles in the village fountain, and in the film’s last stretch, the various characters are storm-tossed in the woods, and ultimately parade around Valerie as she dreams in her bed. The only narrative to speak of is her quest to uncover her true parentage, but she doesn’t seem particularly interested. All the characters insist that she is now a woman, but, like a true adolescent, she hasn’t noticed yet, and treats even the sinister Polecat with a certain amount of amusement and affection – which, I suppose, is how he convinces her to bite a chicken’s neck like a vampire, until it ceases quivering and the blood paints her lips like lipstick. Given that my last viewing was on an old and very unsatisfactory DVD transfer, Criterion’s new Blu-Ray is very welcome, restoring the film’s lush country sensuality and allowing the viewer to pick out every little bizarre detail in the set dressing. A particularly nice feature is the option to watch the film with an alternate 2006 soundtrack by The Valerie Project (think The Alloy Orchestra by way of Ennio Morricone), with a short documentary about the soundtrack’s creation included. The disc also has three shorts by Jires, and interviews, including one with the film’s star, Jaroslava Schallerová, who confesses that being burned at the stake wasn’t as much fun as she made it appear.