“…Cornelius enjoyed [technology] for its own sake. Aesthetically. He had no interest in its moral significance or its utilization. Computers and jets and rockets and lasers and the rest were simply familiar elements of his natural environment. He didn’t judge them or question them, any more than you or I would judge or question a tree or a hill. He picked his cars, his weapons, his gadgets, his clothes – for their private meanings, for what they looked like… He had all the primitive’s respect for Nature, the same tendency to invest it with meaning and identity, only his Nature was the industrial city, his idea of Paradise was an urban utopia…”

“He was a snotty-nosed little back-street nihilist,” [Miss Brunner] said. “There’s no point in dignifying his attitude.”

-Michael Moorcock, The Condition of Muzak (1977)

Of all the novels to adapt into a science fiction film, Michael Moorcock’s The Final Programme, written in 1965-66, was a peculiar choice. Even in the 1970’s it was a peculiar choice, but perhaps there was no other time when it could come into existence, in that hovering period between 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Star Wars (1977), when science fiction actually stood a snowball’s chance in outer space of being taken seriously. Moorcock’s novel was a psychedelic funhouse masquerading as a James Bond-themed science fiction tale. It was the first of a quartet of novels starring Jerry Cornelius, an easy-living playboy with a penchant for fast jets and Rolls Royces, who uses his needle-gun to kill without hesitation, who seduces anything that moves but is only in love with his sister Catherine. Moorcock’s postmodern approach satirized both his own fantasy and SF novels and Britannia as a whole. The books send up imperialism, war and espionage, the sexual revolution, psychedelics, and the music industry. Far from being linear, the plot continually resets itself. Characters die and are resurrected without explanation; Jerry himself is a corpse for much of the series’ third volume. His world is in a state of entropy, and Moorcock cuts from one parallel universe to the next, giving us several versions of Cornelius as well as the recurring supporting cast, until, in the final novel, the characters are revealed as archetypes of the Commedia dell’Arte, playing their parts in an endless cycle while the world falls to pieces and rebuilds itself, over and over again. The novels strike an aloof balance between black humor and resigned melancholy. They’re also collage-like, some of the books scattered with found obit clippings. Sounds like a good time at the movies, doesn’t it?

Jerry Cornelius (Jon Finch) strides through a pinball arcade.

So perhaps the ideal director for such a daunting project was Robert Fuest, who made the Polanski-esque thriller And Soon the Darkness (1970) as well as a pair of stylish and black-humored horror films that injected some much-needed dazzle into Vincent Price’s late career, The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) and Dr. Phibes Rises Again (1972). For The Final Programme (1973) – released in the U.S. as The Last Days of Man on Earth – Fuest receives a “designed by” credit as well as writing and directing. Indeed, it’s a film with a unique look. One early scene takes place in a pinball arcade with human pinballs and giant bumpers. The opening credits sequence is a funeral for Jerry’s father in the desert; the coffin is set ablaze on a pyre while Jerry looks on in a thick fur coat, looking a bit like a Neanderthal that will be appearing at the end of the film; the whole setpiece feels like an echo of 2001. The house of Jerry’s father is like Alice’s Wonderland collapsed inside Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory – but with more overt psychedelics and a lot more hard drugs. One shootout takes place in the Turkish wilderness, with stark widescreen to set up the duel of Jerry and his brother Frank, and swooping helicopter shots over the landscape. The finale takes place in an underground cave excavated by the Nazis, side-by-side with a modern, antiseptic laboratory replete with brains floating in jars (as Jerry notes, “Brainwashing!”). It’s not an expensive film. The special effects themselves are not very special, with the exception of the film’s final, and most brazenly bizarre, shot. Until then, Fuest helps us coast on the strangeness of his stream-of-consciousness spy story, his sharp dialogue playing up the non sequiturs and jokes inherent in Moorcock’s original.

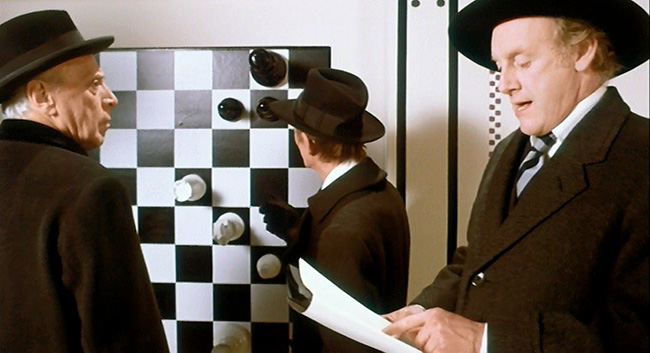

Dr. Powys (George Coulouris), Dr. Lucas (Basil Henson), and Dr. Smiles (Graham Crowden) solve a puzzle inside the booby-trapped home of Jerry’s late father.

Best of all is the casting of Jon Finch as Jerry Cornelius. Finch, a stage actor, had appeared in bit parts in Hammer’s The Vampire Lovers (1970) and The Horror of Frankenstein (1970), sadly underutilized until taking starring roles in two major films: Polanski’s grim, bloody masterpiece Macbeth (1971), and Hitchcock’s uncharacteristically gritty thriller Frenzy (1972). Here, the versatile actor embraces every last peculiarity of Jerry Cornelius. Jerry worships his sister Catherine (Sarah Douglas, Superman) – a plot thread that’s dropped too soon, alas – and kills his druggie brother Frank (Derrick O’Connor, Time Bandits) with pleasure; he is quick to plead for help when he begins to lose a fight against a maniac; he is indifferent as he learns that his business partner, “freelance computer programmer” Miss Brunner (Jenny Runacre, The Canterbury Tales), appears to be absorbing people for food. Jerry is the center of the story only because he must be – there is nothing about him which is particularly heroic or admirable. When his Hindu friend Professor Hira (Hugh Griffith, The Abominable Dr. Phibes) predicts the end of the world, he also prophecies the arrival of “a new messiah, born of the age of science” – and we have no doubt this will be Jerry Cornelius. What we can’t see coming is exactly how that messiah will come about. It’s all wrapped up in a computer program, “a program for the sum total of all human knowledge,” as Miss Brunner puts it, “a program for immortality.” It’s her own ambition, and she needs microfilm from Jerry’s late father, hidden somewhere in his house, only Catherine is being held hostage there, doped-up by Frank Cornelius – look, it’s pointless to describe the plot. Things happen because they happen. Nuns are lined up playing slot machines. Miss Brunner absorbs the wild-eyed Patrick Magee from A Clockwork Orange (1971). Colored gases are pumped from the ceiling. The story is not altogether important, at least not as a story.

Jerry and Miss Brunner (Jenny Runacre) inside her secret laboratory.

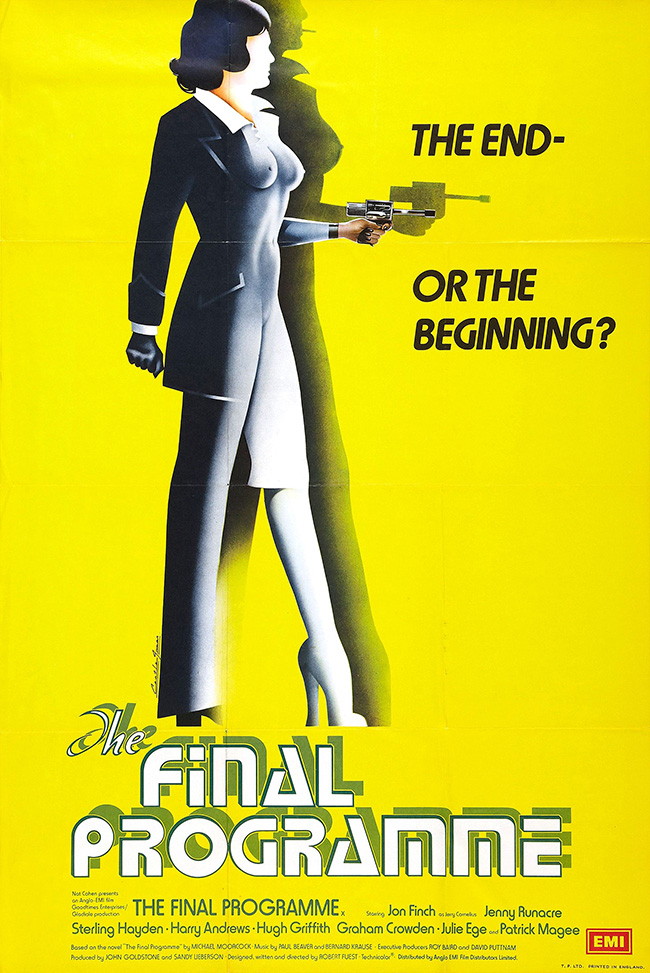

Whether or not the film is successful depends on your expectations, of course. I can’t imagine what someone would think after picking up the third Jerry Cornelius novel because of its genre-standard title The English Assassin. It’s probably the same reaction as American moviegoers drawn to this film with its Last Days of Man on Earth poster, featuring a gun-toting ape-man like another entry in the Planet of the Apes saga. (“The Future is Cancelled!” it declares.) But walk into it with Kurt Vonnegut on the brain and it’s a thoughtful and enjoyably odd satire. As an adaptation it’s surprisingly faithful, although certain elements are given short-shrift in the rush to fit it all into 90 minutes – such as the incest subplot, but more importantly the meaning and impact of the ending. It may be that the best Jerry Cornelius adaptation would take on all four books at once (the quartet was a few years away from completion when this film was made) – if only to capture the Commedia dell’arte finale, with the cast revealing themselves as Pierrot, Harlequin, etc. Certainly Fuest’s film was all-in, so why not? But by the time the quartet was completed, Star Wars was turning science fiction back toward Flash Gordon. Flash Gordon’s a character in Moorcock’s books, by the way. He’s paunchy and wears a raincoat – thus the “Flash” pun. Yes, The Final Programme made its window, and was free and gone from the asylum before anyone could blow a whistle.