How do you classify The 10th Victim (La decima vittima, 1965)? Is it a science fiction satire on our obsession with violence? Is it another James Bond parody, filled to the brim with over-the-top fashions, beautiful women, and cold-hearted assassins? To which Italian cinema tradition does it belong: the 60’s sex comedies about the male ego and the cross-plots of wives and mistresses, or the dream-like, free-riffing fantasies of Fellini? At the start, all those possibilities are in the air, with the sugary score by Piero Piccioni (Contempt) and the large, superstar credits for Marcello Mastroianni (La Dolce Vita) and Ursula Andress (Dr. No) accompanying a street-level gunfight between a Japanese man and a woman in a cow-print shirt. Director Elio Petri (Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion) somehow keeps all these genres and styles in seamless harmony for ninety ridiculously entertaining minutes. The film is an adaptation of a 1953 science fiction story by Robert Sheckley called “Seventh Victim.” (Perhaps the title change is to prevent confusion with Mark Robson’s brilliant 1943 thriller for Val Lewton.) Petri, who shares one of the four screenwriting credits, is faithful to Sheckley’s concept, which speculates a future in which man hunts man, Most Dangerous Game-style, for the televised entertainment of the masses. Those who submit their names for “The Big Hunt” can become wealthy celebrities, but their lives are at risk for the span of ten games. With each hunt, a computer will randomly designate them “Hunter” or “Victim.” A Hunter is given a full description of the Victim he or she must kill, including all social habits. The Victim knows only that a Hunter is on the trail. Survive ten rounds to become a “Decaton,” reaching the height of celebrity and status.

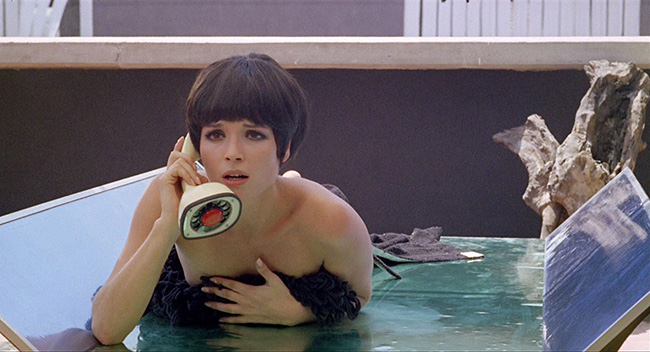

“Hunter” Caroline Meredith (Ursula Andress) poses as a journalist to scope out her “Victim,” Marcello Poletti (Marcello Mastroianni).

The Swiss-born Andress plays Caroline Meredith, an American “from Hoboken.” (I haven’t heard an English dub, but sincerely hope she is given the broadest possible New Jersey accent.) In the opening, she is luring her opponent into a rather antiseptic strip club where she dons a silver masquerade mask, performs a teasing dance, and shoots him with a gun-brassiere, in a moment later borrowed for Austin Powers (1997). Mastroianni is Marcello Poletti, first seen assassinating an equestrian via exploding boot-heels. His winnings are immediately withdrawn from the bank by his wife Lidia (Luce Bonifassy, Playtime), which is a problem, because he’s filed to have his marriage annulled. Waiting in the wings is his mistress, Olga (Elsa Martinelli, Hatari!), who waits impatiently for him to put a ring on her finger, even as his mod apartment is stripped bare by repo men, leaving him with only his pet mechanical robot, which has baby-doll feet and resembles a scrap metal cockroach. He’s assigned to be a Victim, and stoically waits for the attack to come. He visits a Relaxing Station (which offers all forms of comfort, including fairy tale readings and – possibly – sex). He participates in his part-time job as a preacher for an unfashionable religious cult called the Sunsetters, leading a prayer for the sunset behind glass shields that protect him from tomatoes flung by dissenters. And all the while he’s accompanied by a new friend, an American journalist with a film camera in hand, who happens to be Caroline, his Hunter.

Much of the film is a duel between Caroline and Marcello, even if the duel doesn’t involve pistols. He suspects her of being his Hunter, of course, but needs definitive proof before he kills her, otherwise he’ll be imprisoned for murder. She insists he must meet with her film crew at the Temple of Venus, but he refuses to commit. She does have a crew waiting, but they’re preparing to film his death; the Temple of Venus, they’ve decided, will afford the most spectacular location for the confrontation. His killing will be sponsored by the Ming Tea Company, with choreographed dancers and a scripted slogan for Caroline to deliver at the key moment. Marcello, increasingly convinced that she’s his Hunter, begins his own preparations. He sets up a meeting at a club where guns are restricted. There, she is to be launched from an ejecting seat into a swimming pool and the waiting jaws of a crocodile. But until then, she visits his home, meets his jealous wife and lover, and uncovers a secret compartment where he keeps his smiling parents, hiding them from the Elderly Collection Agency. He tries to seduce Caroline, or she tries to seduce him. Finally, he gives himself freely, declaring his love, knowing that dropping his defenses might also mean his death at her hands.

Caroline discovers Marcello’s gun, hidden inside a mechanical toy.

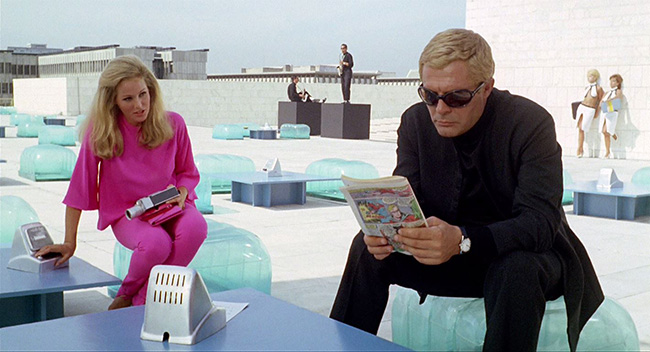

Every moment in the film is infused with details satirical or playfully bizarre. A loudspeaker at the Department of the Big Hunt delivers propaganda like, “An enemy a day keeps the doctor away,” and “Why control birth rates when we can control death rates?” At a shooting range that resembles one of Q’s test labs, Marcello confers with a master of arms who has a hook for a hand, false teeth, and a false chin. The crocodile handler speaks through a tracheotomy voicebox, and his assistant is bandaged from head to toe. These MAD Magazine details foreshadow Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), but the eye-popping colors remind of Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits (1965) and his “Toby Dammit” segment of Spirits of the Dead (1968). Director Petri wisely makes the most of his Roman setting, and plays up the story’s theme of gladiatorial combat by featuring actual Roman gladiators fighting at a nightclub. (Caroline’s film crew abandons the idea of shooting Marcello’s death at the Colosseum because it has “too many holes.”) Ultimately, however, this is a battle of the sexes, as made clear by the film’s multiple climactic twists, strung together in an absurd chain of shootouts, marriage proposals, and violent breakups. Fans of Italian cinema will be accustomed to glamorous women fighting over the charms of Marcello Mastroianni. But in The 10th Victim, this combat is rendered in the bright pop art of comic books – or, as they’re called in the film, “the classics.” The idea of a modern, commercialized society embracing gladiatorial violence has started to feel a little stale: movies like The Running Man (1987), Series 7: The Contenders (2001), and The Hunger Games (2012) have thoroughly trampled this ground. The 10th Victim feels fresh because it has more on its mind. We’ve always been at each other’s throats, the film contends: it’s just love and marriage, Italian style.