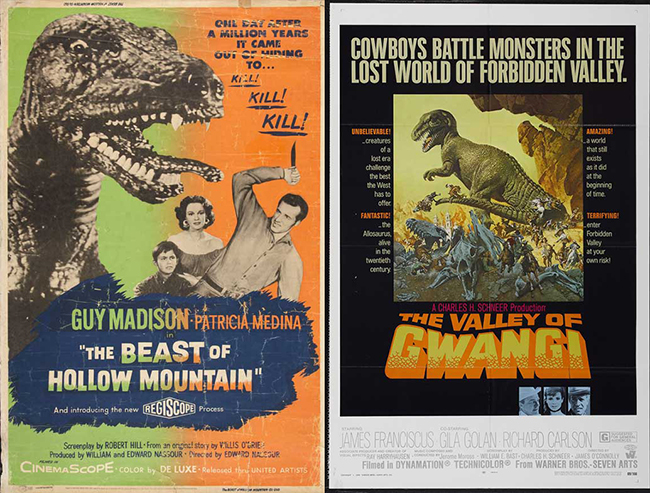

Cowboys vs. dinosaurs! The idea was kicking around in stop-motion animator Willis O’Brien’s head for a while in the years following his seminal work on The Lost World (1925) and King Kong (1933). It was an appealing and original notion to mash together the two genres, and became a recurring theme among the multiple projects he tried (and usually failed) to sell to studios. One of these unrealized projects was developed with his apprentice Ray Harryhausen, with whom O’Brien had collaborated on Mighty Joe Young (1949). The story was initially called El Toro Estrella (The Star Bull), later retitled The Valley of the Mist, and concerned a boy, his bull, and a lost valley of dinosaurs. Another O’Brien project from earlier in the 40’s, Gwangi, featured cowboys lassoing a dinosaur in the hidden “Valley of the Ancients,” somewhere near the Badlands. According to Harryhausen in An Animated Life (2003, co-written by Tony Dalton), “The ill-fated Gwangi was originally to have been a Technicolor co-production between RKO Radio Pictures and Colonial Pictures, but after RKO had spent almost a year in preparation and $50,000, they decided, for cost reasons or perhaps the war, to abandon it.” Harryhausen was intrigued by both projects, but for the time being they languished. In the mid-50’s, O’Brien finally sold a similar concept to producers Edward and William Nassour. Edward Nassour was a stop-motion animator himself, and the resulting film, The Beast of Hollow Mountain (1956), would showcase his “Regiscope” process using a dinosaur model by Henry Lyon. O’Brien, for whatever reason, would not contribute to the stop motion. It would be a Nassour brothers film.

“The Beast of Hollow Mountain”: Jimmy (Guy Madison) has a liaison with the lovely Sarita (Patricia Medina) in a Mexican graveyard.

The Beast of Hollow Mountain was a Mexican co-production, and the story takes place in Mexico, with Guy Madison, star of the TV series The Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok, playing cowboy cattle rancher Jimmy Ryan. He owns the Rancho Bonito with his ranch hands Felipe (Carlos Rivas), the alcoholic Pancho (Pascual García Peña), and Pancho’s son Panchito (Mario Navarro). (Both Rivas and Peña appear in 1957’s The Black Scorpion, which does feature stop motion effects by O’Brien.) Cattle frequently go missing in the vicinity of the nearby Hollow Mountain and its vast swamp, home to many ominous legends. But Jimmy is inclined to believe that the real culprit is his bitter rival Enrique (Eduardo Noriega), who is engaged to the beautiful Sarita (Patricia Medina, future wife of Joseph Cotten). When Sarita and Jimmy develop feelings for one another, Enrique goes into a jealous rage, planning to steal Jimmy’s cattle to send them on a stampede through the town square. But all are surprised at the reveal of Hollow Mountain’s guardian, the true cattle rustler: a Tyrannosaurus Rex/Allosaurus which goes on a rampage through the swamp and desert, pursuing both Jimmy and Enrique.

The “Beast of Hollow Mountain” stomps through the swamp.

The Beast of Hollow Mountain commits the cardinal sin of withholding its monster for a full hour, giving little indication – apart from the title – that there even will be a beast. In the meantime, it’s actually a very attractively shot Western, in widescreen, full-color Cinemascope. Directors Edward Nassour and Ismael Rodríguez (who presumably tackled the Spanish-language production filmed simultaneously) at least keep things mildly diverting. The Mexican locales provide some much-needed authenticity, including a wedding fiesta with fireworks and colorful masks. There are also a handful of dynamic compositions, such as Madison entering a Mexican graveyard by horseback, surrounded by painted and decorated tombstones. The story, of course, is utterly run-of-the-mill, and any monster kids who showed up to see cowboys fighting dinosaurs will instead squirm through an hour of watching Jimmy and Enrique bicker over Sarita. When the dinosaur finally does arrive, the switch to an obvious model, crudely animated on a miniature set that doesn’t match the live action footage, can only produce laughter. Both O’Brien and Harryhausen were always much more careful about how their animation was introduced and subsequently integrated into the story. It doesn’t help that everything that came before in Hollow Mountain does look so good; it’s like a teenager’s animation test films were suddenly inserted into a major Hollywood movie. Nassour’s “Regiscope” is described thusly in Mike Hankin’s Ray Harryhausen: Master of the Majicks, Vol. 1: “Like the Puppetoons, The Beast of Hollow Mountain used a series of replacement puppets for a walk/run cycle in addition to the main armatured foam rubber puppet that was animated in the conventional way…The replacement animation stands out quite distinctly from the regular stop motion animation and appears very cartoony.” Adding to the cartoonish quality is a flickering red tongue, which extends far out of the jaws, emphasizing not just a lizard quality but also the effect’s inescapable silliness. Of course, the climax is still fun to watch, largely for all these reasons. Where else can you see Guy Madison lassoing a tree branch, swinging from the rope over a pond, then jumping over a dinosaur? To the film’s credit, it is groundbreaking in one respect: the stop motion was in color and Cinemascope. Harryhausen would not attempt color for another two years, with The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), and avoided the technical problems of applying his Dynamation process to Cinemascope until First Men in the Moon (1964).

“The Valley of Gwangi”: Horse, meet Eohippus.

O’Brien did find some more stop motion work, and his talents grace The Black Scorpion (1957), The Giant Behemoth (1959), and, briefly, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), his last FX contribution before his death in November 1962. Harryhausen, meanwhile, had hit his stride, and made stop motion a box office draw again thanks to a number of 50’s creature features including the bar-raising 7th Voyage of Sinbad. After the blockbuster success of the prehistoric-themed, fur-bikini-clad One Million Years B.C. (1966), Harryhausen was given sufficient leverage to finance another dinosaur picture. He turned to the old, abandoned projects of his mentor, and selected the one which had enthralled him the most: Gwangi. It was retitled The Valley of Gwangi (1969) and relocated from the American Badlands to somewhere “south of the Rio Grande at the turn of the century,” as the narrator tells us. Once again Harryhausen’s longtime partner Charles H. Schneer would produce, and the production was filmed in Spain, standing in for Mexico. Unlike The Beast of Hollow Mountain, there would be dinosaurs aplenty, and you wouldn’t have to wait until the end of the film to see them. Although O’Brien’s script was rewritten, the basic structure was the same: cowboys discover a lost valley of dinosaurs, and one, nicknamed “Gwangi,” is captured before breaking loose and going on a King Kong-styled rampage.

A Pteranodon hoists a cowboy off his horse in “The Valley of Gwangi.”

TV star James Franciscus, who would soon replace Charlton Heston for the first Planet of the Apes sequel, plays Tuck, a former stuntman looking to buy out the wild west show owned by his horse-diving ex-girlfriend T.J. Breckenridge (Gila Golan, Our Man Flint). T.J. has recently acquired a prehistoric Eohippus – like a miniature, miniature horse – from out of the Mexican wilderness, and hopes the find will prove lucrative for her show. A paleontologist, Professor Bromley (Laurence Naismith, Jason and the Argonauts), properly identifies the specimen, and with the aid of the Eohippus they discover its home, Forbidden Valley – accessible only by blasting their way through rocks. In the valley they quickly encounter a number of Lost World sights: a Pteranodon (who lifts one cowboy off his saddle), an Ornithomimus, a Styracosaurus, and a Tyrannosaurus Rex, which they manage to capture after a long struggle, delivering it back to T.J.’s circus as a new spectacle, “Gwangi.” By design, Gwangi has features of both a T. Rex and an Allosaurus – Ray modified the creature until it was the ideal hybrid of both, which actually makes it similar to the Beast of Hollow Mountain, with more accurate muscle definition and minus the ridiculous tongue. When Gwangi quickly gets loose, it battles a stop motion circus elephant before a stand-off inside a burning church.

Gwangi duels with a Styracosaurus in Forbidden Valley.

At this stage of his career, Harryhausen had mastered his craft and was looking for new innovations. A major highlight is the lassoing sequence: the moment from O’Brien’s original proposal which so captivated him in the first place. When the lassos drop and tighten around Gwangi’s neck, the integration between the model dinosaur and the projected background is seamless. This was achieved by having the actors lasso a jeep with a pole mounted on it; Harryhausen has the dinosaur stand in front of the jeep, with the loops of the lassos animated about his neck. A dinosaur prop is used for close-ups after the creature is captured, which, though imperfect, is still much better than the giant rubber feet deployed in Hollow Mountain. The Valley of Gwangi is classic Harryhausen, featuring a number of his creations ranging from the cute (the Eohippus) to the realistic (the elephant, as well as an animated horse-diving shot) to the awe-inspiring. Forbidden Valley is an O’Brien trope, another of his Lost Worlds, and as soon as the cowboys penetrate it, Harryhausen, the world’s biggest King Kong fan, lets loose with all the dinosaur action he can breathlessly animate. This has made the film beloved among fans over the intervening decades, even though it underperformed at the box office. The animator blamed a poor publicity campaign, but also stated in his autobiography, “I wish the film had been released five years earlier.” By 1969, the subject matter – which O’Brien originated in the 40’s – perhaps sounded too juvenile or quaint to audiences. It would be the last dinosaur film in Harryhausen’s career, but it’s a satisfying send-off, and the Wild West spin makes the material feel fresh even today. It’s grand monster-movie spectacle that could only come from the combined imaginations of Harryhausen and his idol, Willis O’Brien.