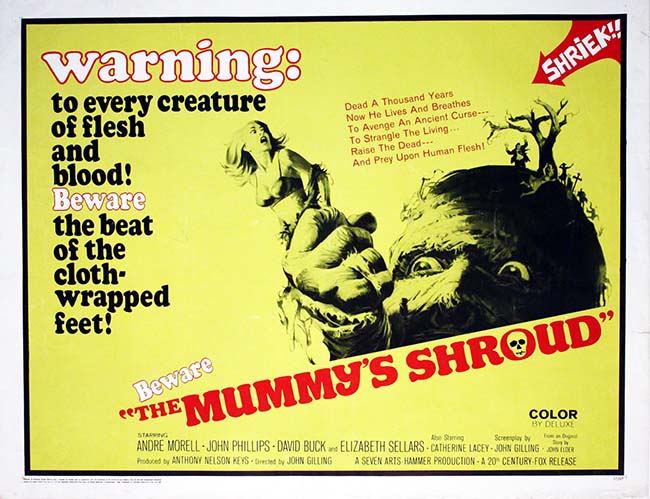

Hammer’s Mummy films were always a bit of a second tier series for the studio. The first film, The Mummy (1959), was an obvious decision to capitalize on a deal with Universal to remake their classic monsters, following Hammer’s success with the literature-based The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958). The Mummy also offered an opportunity to reunite Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, and director Terence Fisher – a third go at box office success using more or less the same formula: Cushing as the driven protagonist, Lee as the monster. But as Hammer entered the 60’s, an efficient commercial strategy emerged which divided the talent, assigning Cushing to the Frankenstein sequels and (eventually) Lee to the Draculas. A loose continuity was established in each series, lending a certain added interest. How will Dracula be revived this time? What new monster will emerge from Frankenstein’s lab? Meanwhile, the Mummy series lumbered forward with none of these luxuries: no Cushing, no Lee, no continuity. The first follow-up came relatively late, in 1964, with The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb, directed by Michael Carreras, future chief executive of Hammer. Though the film lacked the original’s elegance and scale, it at least provided an entertaining turn by Fred Clark (Sunset Blvd.) and the expected monster-movie beats. Three years later the penultimate entry arrived, The Mummy’s Shroud (1967), released on a double bill with Fisher’s Frankenstein Created Woman (1967). Fisher’s film was more original, sensitive, and complex than its exploitation-ready title suggested; the latest Mummy movie could only suffer by comparison. Without radical reinvention, there’s only so much a Mummy sequel can do. And that sort of rethinking would not happen until the last entry in the series, cult favorite Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971), in part because it adapted a Bram Stoker novel rather than following the standard template. But that’s not to say The Mummy’s Shroud is without interest; for one thing, it actually contains the best vanquished-monster special effect since Lee crumbled into dust in Dracula.

Hammer’s Mummy films were always a bit of a second tier series for the studio. The first film, The Mummy (1959), was an obvious decision to capitalize on a deal with Universal to remake their classic monsters, following Hammer’s success with the literature-based The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958). The Mummy also offered an opportunity to reunite Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, and director Terence Fisher – a third go at box office success using more or less the same formula: Cushing as the driven protagonist, Lee as the monster. But as Hammer entered the 60’s, an efficient commercial strategy emerged which divided the talent, assigning Cushing to the Frankenstein sequels and (eventually) Lee to the Draculas. A loose continuity was established in each series, lending a certain added interest. How will Dracula be revived this time? What new monster will emerge from Frankenstein’s lab? Meanwhile, the Mummy series lumbered forward with none of these luxuries: no Cushing, no Lee, no continuity. The first follow-up came relatively late, in 1964, with The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb, directed by Michael Carreras, future chief executive of Hammer. Though the film lacked the original’s elegance and scale, it at least provided an entertaining turn by Fred Clark (Sunset Blvd.) and the expected monster-movie beats. Three years later the penultimate entry arrived, The Mummy’s Shroud (1967), released on a double bill with Fisher’s Frankenstein Created Woman (1967). Fisher’s film was more original, sensitive, and complex than its exploitation-ready title suggested; the latest Mummy movie could only suffer by comparison. Without radical reinvention, there’s only so much a Mummy sequel can do. And that sort of rethinking would not happen until the last entry in the series, cult favorite Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971), in part because it adapted a Bram Stoker novel rather than following the standard template. But that’s not to say The Mummy’s Shroud is without interest; for one thing, it actually contains the best vanquished-monster special effect since Lee crumbled into dust in Dracula.

Fortune teller Haiti (Catherine Lacey) and her son Hasmid (Roger Delgado) plot against the raiders of a Pharaoh’s tomb.

It seems that an elaborate backstory is a requirement for Mummy films, so for Shroud we are given a long prologue in which we learn of the rivalry between an Egyptian Pharaoh and his brother. When the jealous brother murders the Pharaoh, his orphaned son, Prince Kah-to-Bey, is taken into the desert by a loyal slave named Prem. There, Kah-to-Bey gifts the Seal of the Pharaoh to Prem, then dies. Prem buries his master in a secret tomb, draping a sacred shroud over his body. These scenes are unconvincingly staged, with a much smaller budget than the original Mummy, but the film picks itself up after a stumbling start. In 1920 Egypt, Prem’s mummified body has been recovered and put on display, but has been mistaken for Kah-to-Bey, since he was discovered with the Seal of the Pharaoh. Archaeologist Sir Basil Walden (André Morell, The Hound of the Baskervilles) believes Kah-to-Bey’s true burying place has yet to be found, and so he embarks on an expedition funded by the arrogant, self-promoting Stanley Preston (John Phillips, Village of the Damned). Walden’s team includes the clairvoyant Claire (Maggie Kimberly, Witchfinder General), Preston’s son Paul (David Buck, of TV’s Mystery and Imagination), and photographer Harry (Tim Barrett, The Deadly Bees). They discover the shroud-covered Kah-to-Bey preserved in the sand, and reunite the young Pharaoh with the mummified Prem in Walden’s collection of antiquities. But rumors of a curse begin to spread. While excavating the tomb, Walden is bitten by a snake, and suffers from the effects; Preston, eager to take all the credit for the discovery, has Walden committed to an insane asylum. Then an old Egyptian fortune teller, Haiti (Catherine Lacey, The Lady Vanishes), and her son Hasmid (Roger Delgado, The Terror of the Tongs), command Prem to rise from the dead to murder the members of the expedition one by one in punishment for desecrating the Pharaoh’s tomb.

The mummy stalks Sir Basil Walden (André Morell).

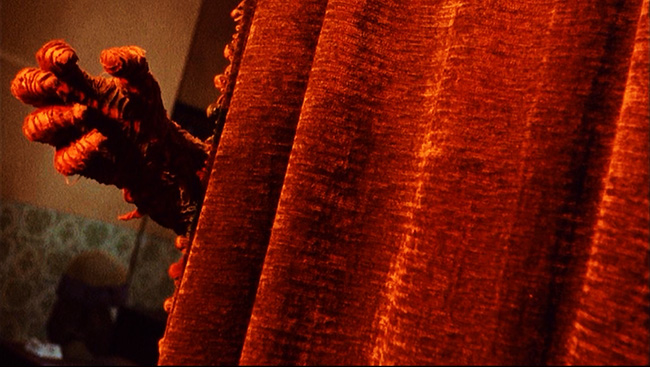

This was the last Hammer film directed by John Gilling, who helmed the studio’s The Shadow of the Cat (1961), The Pirates of Blood River (1962), The Scarlet Blade (1963), The Brigand of Kandahar (1965), The Plague of the Zombies (1966), and The Reptile (1966). He wrote the screenplay from a story supplied by Anthony Hinds, executive producer and, at the time, the driving creative force behind Hammer horror. There’s a slapdash quality to the scenario: apart from borrowing its basic outline from every mummy film that had come before, there’s an occasional inattention to detail, such as the fact that the tomb is discovered near “The Rock of Death,” and at the climax Claire must read “The Words of Death.” And this is one of those movies in which a crystal ball has all the magical properties of a TV set. But Gilling understands this is basically pulp, and he treats it as such. The mummy attack scenes are a highlight: Gilling uses canted angles, dynamic compositions, and vivid colors to accompany the surprisingly brutal murders, lending the film an E.C. Comics vibe. Harry’s murder takes place in a darkroom lit blood-red while he’s stooped over developer; he is burned in chemicals and set on fire. Hammer regular Michael Ripper, turning in an endearing performance as Preston’s long-suffering servant, is wrapped in a bedsheet and flung through a window to the street below. Preston simply gets his head bashed against a wall. Gilling initiates this dream-like atmosphere with the arrival of the mummy Prem, usually introduced obliquely: in a reflection in a crystal ball, or a shadow in an alleyway, or a claw-like hand pulling back a curtain, or – when Ripper is without his thick glasses – out-of-focus.

Prem (Eddie Powell) with axe.

After the mummy tries to attack Paul with an axe (!), Claire speaks the magic words to destroy him. (She must also deliver a sincere apology in ancient Egyptian.) Prem begins to disintegrate, clawing at his bandaged head. While his flesh crumbles into dust, he exposes a skull, which also breaks apart, his fingers still digging away at what’s left. For 1966, when Hammer was in the business of spitting out these horror films as fast as possible, it’s surprising to see such care and imagination poured into the special effect – and of course it also works as an homage to Lee’s demise in Dracula. That’s fitting, because this was the last Hammer film to be shot at storied Bray Studios. (Hammer had begun relying upon Elstree Studios in 1964.) So with Gilling’s departure and Bray largely shuttered, The Mummy’s Shroud feels like the end of an era; ahead was more sex and violence, edgier exploitation as the 70’s loomed. Bearing this in mind, The Mummy’s Shroud can be forgiven if it feels a bit dustier than intended.