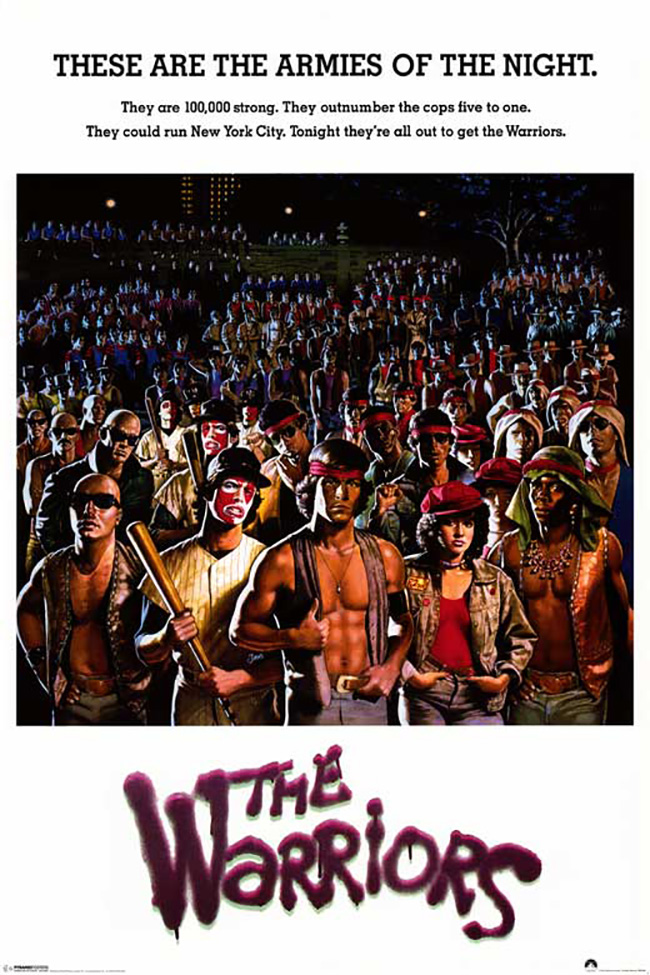

Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979) intends to make the viewer uncomfortable from the very start. He plunges us into a New York City overrun with street gangs, with no traditional audience surrogate, no Serpico. The opening credits of red spray paint follow an underground train down dark tunnels. The varied gangs gather in matching uniforms: dapper black men in purple vests and black hats; a group wearing camouflage; Chinese; greasers; the “Electric Eliminators”; even mimes in suspenders and white face-paint. A map of the subway system is scanned slowly as the Warriors – the Coney Island-based gang we’ll be following – makes their way up toward the Bronx. They, too, are wearing their colors, a jacket with “Warriors” on the back. Taking place over the course of one long night, The Warriors depicts an almost empty NYC – nothing but gangs and the cops trying unsuccessfully to round them up. Occasionally we see someone that falls outside this dichotomy: commuters jostled by gangs in the subway; a girl manning a magazine and cigarette stand asking a gang leader weakly, “Hey, what about the money you owe?” after he’s been taking freely from her goods. These straights are few and far between. The trains are mostly empty, and have the atmosphere of an Argento horror film. You wait for something very bad to happen. Yet toward the end of the film, when two young couples stumble onto the train in formalwear – straight from prom perhaps – they look as strange to us as that mime gang from the beginning of the film. The kids are freaked out by the dead stares and black bruises of the Warriors, and vacate the car. We’re sitting beside the Warriors, having endured the brutal night alongside them, all too happy to see that teenage riff-raff leave.

A member of the Baseball Furies.

Hill likes to think of his films as Westerns, the plot and dialogue spare and direct. The Warriors is a superb example of this approach. Intentionally, the dialogue lacks elegance; it’s mostly profanities and barked commands. And the set-up is simple: at a gathering of the NYC gangs, Cyrus (Roger Hill), leader of the powerful Gramercy Riffs, announces the time is nigh to take over the city once and for all. He’s assassinated during his speech by Luther (David Patrick Kelly, 48 Hrs.), the leader of the Rogues, who is then able stir up a mob against the head of the Warriors, accusing him of the deed. The remaining Warriors escape into the streets. The Riffs put the word out that the Warriors must be found: a DJ (Lynne Thigpen, Tootsie) working for the Riffs makes the call to action, playing “Nowhere to Run.” Swan (Michael Beck, Xanadu) establishes himself as the Warriors’ new leader, at least until they can get back to the safety of their Coney Island homebase; it’s a decision that riles the ambitious, temperamental Warrior Ajax (James Remar, Drugstore Cowboy). They hop a train, which puts on the brakes when the tracks are blocked by flames. Driven back into the streets, the Warriors contend with one gang after another, all anxious to take vengeance for Cyrus’ death and gain cred with the Riffs. The Warriors also tangle with cops, jealousy, and young lust. An all-girl gang called the Lizzies lures three of the Warriors into their pad, where they turn on them with guns and switchblades. Ajax nearly rapes a girl on a park bench, who reveals herself to be an undercover cop and takes him down. Swan becomes reluctantly involved with a prostitute named Mercy (Deborah Van Valkenburgh, Streets of Fire) who tags along, anxious to leave her depressing corner of the city (and a group called the Orphans, too small time to be invited to the Riffs’ summit).

Deborah Van Valkenburgh as Mercy.

If names like Cyrus and Ajax send up any flags, your instincts are correct – The Warriors plays like a Greek epic, with archetypes, digressions, and a sense of the tragic. The original 1965 novel by Sol Yurick makes the connection more explicit: the story adapts The Anabasis by the ancient Greek historian Xenophon, telling of his real-life exploits with the Ten Thousand. The Ten Thousand were warriors hired by Cyrus the Younger, who marched them to Persia to oust his brother from the throne. But Cyrus was defeated, leaving the Ten Thousand to fight their way out of Babylon and embark on a long journey until they finally reached the Black Sea (crying out, “The sea, the sea!”). In Hill’s film, the Warriors place just as much importance on finding the sea, their home at Coney Island. The final confrontation, with Luther and his Rogues, takes place at the beach on a gray morning. This primal, ancient narrative beneath The Warriors contrasts starkly with the 70’s-era urban street scene, the stunted conversations, crude taunts and aimless violence. Hill pushes his vision of the city even further, into dystopia; though science fiction elements are absent, it’s evident this New York City is a near-future which is only a few steps away from Escape from New York (1981). That film might as well be a sequel, and makes for a perfect double feature.