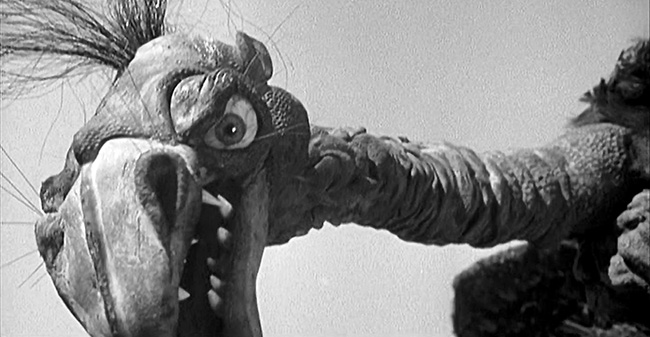

“Honest to Pete, I’ll never call my mother-in-law an old crow again!” says the fighter pilot as he engages with The Giant Claw (1957), the winged beast also known by its French-Canadian moniker “La Carcagne.” The size of the creature is indeterminate, since it seems to radically change scale from one scene to another. But it has a vast wingspan, and don’t mistake its plumage for real feathers, for they are made of no substance known to man. They do, however, resemble turkey feathers, and La Carcagne looks an awful lot like a cross between a vulture and a turkey. Or perhaps a gangly puppet, which is understandable because the wire keeping its head up or swinging its body to and fro is visible in many shots. Its eyes are like ping pong balls, bulging out of its head, which is otherwise mostly beak. A tuft of hair floats above its crown, giving it a certain raging-old-man aspect. (It would be easy to imagine the Giant Claw shaking a cane at some kids.) In an age of giant-sized, usually radiation-mutated beasties, not every studio could afford the time and talents of Ray Harryhausen, who crafted the memorable monsters of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955). Nor could every studio splurge on the elaborate miniatures of Toho’s new kaiju pictures. Sure, you could always strap an appendage to a gila monster to make it look more prehistoric, or use optical effects to make a critter look huge, Bert I. Gordon style, but what if you had to make a monster from scratch on a minuscule budget? Producer Sam Katzman and director Fred F. Sears, who both teamed on the Harryhausen picture Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), settled on the clumsy puppet which, in all fairness, is the only reason anyone remembers The Giant Claw in the first place.

Mitch MacAfee (Jeff Morrow) and Sally Caldwell (Mara Corday) ponder the threat of The Giant Claw.

Jeff Morrow (This Island Earth) stars as Mitch MacAfee, an aeronautics engineer who thinks he’s encountered a UFO, but radar detects nothing. In fact, for a good portion of the first act The Giant Claw plays as a UFO movie, an exploitation film on the decade’s interest in flying saucers and alien visitations, among other movies like The Flying Saucer (1950), Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, and UFOs: The True Story of Flying Saucers (1956). But it soon becomes clear that the object, which they call “a flying battleship,” is an out of focus blob for a reason. Mitch comes to realize that the object of his obsession is a giant alien turkey. A trip to Canada uncovers a giant claw print and a terrified French Canadian who speaks to the legend of “La Carcagna,” a deadly bird. But the lack of radar evidence means that the only person who believes Mitch is mathematician Sally Caldwell (Mara Corday, who appeared in better films of this type: Tarantula and the Willis O’Brien-animated The Black Scorpion). Her loyalty is immediately assumed to be romantic interest by 50’s chauvinist Mitch, who kisses her on the mouth while she’s trying to take a nap on the plane. Their subsequent flirtation is worth reproducing in its entirety:

“Where did that impulse come from?”

“Left field, maybe.”

“I like baseball.”

“Or maybe just sitting next to a pretty girl. That’s enough in itself sometimes.”

“Even sitting next to Mademoiselle Mathematician? Or should we stick to the baseball reference?”

“There are figures and there are figures.”

“Inescapable logic. Corny, but true. You almost overwhelm me.”

“Almost? Well, let’s finish the job. Look at that moon.”

[He indicates the moon out the window, then tries to kiss her again.]

“Speaking of baseball and left field, somebody warned me that you make up your own rules.”

“Whoever said that’s no friend of mine.”

“Well, he’s a friend of mine.”

“Sabotage!”

“Oh, much too dramatic. Let’s stick to baseball and try instead, ‘Out, trying to steal second.'”

“Back to the bush leagues. Finished.”

“A quitter, I knew it. No fight, no spirit.”

“Of course the umpire could always reverse a decision.”

“No, no short cuts. Must follow the pattern. You see, first the minor leagues, and then the major leagues. I stick to the rules, Mitch. Sorry about that.”

The Giant Claw tears up a forest.

Sally’s phrase “must follow the pattern” triggers Mitch to pull out a map of Canada and mark the sightings of the Giant Claw. Although there haven’t been that many sightings, somehow he extrapolates the few dots into a giant spiral pattern. At this point it would be understandable for the viewer to question Mitch’s sanity; although we have seen the Giant Claw for ourselves, its gawky, Muppet-like appearance is surely just a product of Mitch’s raving lunacy, right? After all, no radar has detected its presence. But the Claw is soon tackling jet planes and swallowing the pilots attempting to parachute to safety. Mitch theorizes, rationally, that the Claw is attracted to movement. After all, everything it’s attacked so far has been moving. This leads to a montage in which martial law is instituted, curfews are established, and residents are warned to limit movement as much as possible. When Mitch and Sally are racing away in a vehicle, they are wise enough to leave their headlights switched off – unlike those laughing teenagers speeding past them. “Come on man, make this thing go!” one teen urges his friend. “Let’s get some speed on this! Oh, man, you ain’t movin’ at all!” Thus he demonstrates his doomed passion for movement – drawing the attention of La Carcagna, who lifts the car off the road and drops it. The car explodes in mid-air.

The Giant Claw attacks New York City.

The reason missiles and bombs cannot harm the creature – and that it can’t be detected by radar – is that it’s surrounded by a shield of antimatter. This is explained in a long sequence in which Mitch illustrates what antimatter is, though the short of it is that he and Sally need to build an experimental gun which can disrupt the bird’s antimatter shield. While the Giant Claw descends on New York City, straddling the Empire State Building like King Kong – but pausing to take a bite out of it – the air force mobilizes. The Claw moves on to the United Nations Building. People in stock footage flee for safety (one very brief shot of falling debris appears to be borrowed from Earth vs. the Flying Saucers). When the extraterrestrial bird begins pursuing the plane with Mitch, Mitch fires his anti-antimatter gun, leaving it vulnerable. The air force takes it down. Screaming, the Giant Claw collapses into the ocean, which looks exactly like the prop being contemptuously flung into a puddle. (I have to assume it was the last day of shooting.) Apart from its absurd special effects – a lowlight is the Claw lifting a model train into its mouth and carrying it around the sky like a string of sausage links – The Giant Claw follows the standard formula of these pictures: square-jawed hero; brainy female heroine; newsreel-style narration; stock footage, stock footage, stock footage; disaster movie climax. But the Z-grade special effects actually make the film more special than it might have been. The whole feels like a parody of atomic age monster movies. Unsurprisingly it was heavily featured in Joe Dante’s roadshow clip-show The Movie Orgy, which played up the comedy of The Giant Claw by mixing it in a blender with other B-movies, including The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958). Why the film never made it to Mystery Science Theater 3000 is a mystery, although, like Plan 9 from Outer Space, it largely riffs itself.