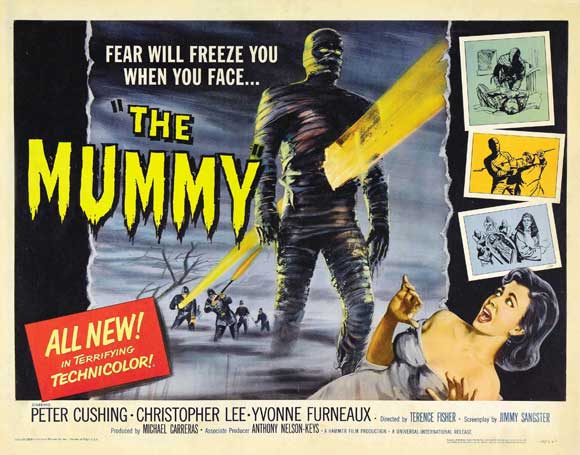

The Mummy (1959) was the third in Hammer’s classic trilogy of Peter Cushing/Christopher Lee match-ups, revisiting and revitalizing classic monsters of horror. The first, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), completely reimagined the Mary Shelley novel and, like the studio’s earlier SF hit The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), exploited its X rating with touches of gore. Dracula (Horror of Dracula, 1958) let Lee out of the heavy makeup to prove that he could be a sexy, if blood-craving, gentleman villain. By the time of The Mummy, the Hammer horror formula was well established. Cushing would get top billing as the charming, erudite, scholarly lead; Lee, following in the footsteps of Chaney, Karloff, and Lugosi, would bring the monster to life. Once again, director Terence Fisher was at the helm. Also returning was screenwriter Jimmy Sangster, now drawing not from literature but Universal’s sometimes-creaky Mummy series. (With Universal now its American distributor, Hammer enjoyed the luxury of raiding the Universal canon.) The sweeping, Egyptian-themed score was by a newcomer to the Hammer horror team, Franz Reizenstein (Circus of Horrors), a Jewish, German-born composer who fled Nazi Germany in the 30’s, and who brought a distinguished pedigree to this pulp outing. With these elements in place, the superior results were to be expected. Hammer was in its golden age. Consider that at one point in the film Cushing, 46, is referred to as a “boy.” There is a youthful excitement running vibrant throughout this classy British production, as though animated by the film’s “Scroll of Life.”

Peter Cushing as Egyptologist John Banning.

Even though Sangster wasn’t drawing from a classic horror novel, The Mummy – like Curse of Frankenstein – has a novel-like structure, patiently establishing its characters and themes before bringing us to the inevitable violence and murders. It’s in no hurry. Given that the story is actually very simple, Sangster’s narrative – which skips ahead in time, then drops us into ancient history, then back to the present, then loops back to revisit the events at the start of the film from a different perspective, before skipping back to the present for a climax – is a bit of a con to make the film seem more complex than it actually is. The first two sequels, The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (1964) and The Mummy’s Shroud (1967), have a harder time disguising the crude simplicity of the formula. But Sangster treats the well-worn material with fresh eyes and a sense of respect, laying the groundwork for Fisher’s direction to make the prototype Hammer mummy picture a first-class production. Cushing plays John Banning, who at the start of the film has broken his leg at the site of a tomb excavation in 1895 Egypt, reluctantly leaving most of the oversight to his elderly father Stephen (Felix Aylmer, Henry V) and his partner Joseph Whemple (Raymond Huntley, The Dam Busters). As Stephen and Joseph enter the tomb of the Princess Ananka – lit in eerie (and inexplicable) green light – Stephen is left temporarily alone. When Joseph returns, Stephen is raving mad, apparently the victim of an ancient curse, as warned against by one Mehemet Bey (the always-great George Bastell, of The Stranglers of Bombay).

Christopher Lee as the High Priest Kharis.

Three years later, in England, Stephen Banning is confined to a padded cell in an insane asylum when a reanimated mummy (Lee) breaks through the barred window and strangles him. John Banning, enduring a permanent limp from having never properly set his broken leg, witnesses the murder of Joseph when the mummy breaks into their study and proves impervious to John’s pistol. John tries to convince a skeptical police inspector (Eddie Byrne, Jack the Ripper) of what he’s seen, but the inspector only begins to believe after questioning the locals (among them, inevitably, Hammer regular Michael Ripper). A very extended flashback, narrated by John, reveals the backstory of the Princess Ananka (Yvonne Furneaux, La Dolce Vita) and the High Priest Kharis (Lee). After Ananka dies and is sealed in her tomb, Kharis, who loved her, attempts to resurrect her using the Scroll of Life. He is caught in the attempt, has his tongue cut out, and is sentenced to being wrapped in strips of cloth and sealed in the tomb alive. In another flashback, we see what drove John’s father insane: Kharis the mummy stepping out from his crypt and almost killing him before being halted by Mehemet Bey, who steals the Scroll of Life. Now Bey is using the mummy to murder those who desecrated the tomb of Ananka. As a further wrinkle – albeit a predictable one – John’s wife is a dead ringer for Ananka (and is played once again by Furneaux).

The mummy attacks John Banning.

Although it’s obvious the Egypt scenes were shot on an enclosed set with a backdrop, this is nonetheless a handsomely mounted Hammer film, more lavish, and with a greater attention to detail, than many of the studio’s later efforts (as budgets became more crunched, and production schedules became more ambitious). Fisher is at the top of his game and keeps things visually interesting even when the script is saddled with exposition, from the colorful, eerie tomb of Ananka to the wide picture windows of Banning’s study (we keep watching the windows, expecting the shape of the mummy to appear at any moment). The swamps that seem to surround Banning’s house might be the best tribute to Universal of all; the England of The Mummy seems to be in the act of slowly sinking into a great bog, the antiquities decorating the home of Banning and his rival Mehemet Bey (who lives just the other side of the murk, having recently immigrated from Egypt) only temporarily lifted from their tombs and temples, soon to be devoured by the preserving muck of the earth once again, perhaps for later excavations to discover. That, of course, is the fate of Lee’s mummy, who disappears slowly into the bubbling, fog-draped swamp. Lee, who is forced to endure a suffocating makeup job by Roy Ashton that obscures all features but his eyes, nonetheless makes the most of it, with ferocious attacks on his enemies (as targeted by Bey) and eyes that translate the recognition of his reincarnated Ananka, and lets the audience know exactly when he must turn on the one who’s controlling him and why. Although the straightforward story lacks the layered themes of Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula, The Mummy is still one of the lustrous jewels from Hammer’s reign. The new Blu-Ray is part of Warner’s box set Horror Classics Volume One, alongside Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), and Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970). It’s reportedly the same (fabulous-looking) HD transfer as the one released earlier in Hammer’s Region 2 release, but, unfortunately, Warner hasn’t carried over any of the extras.