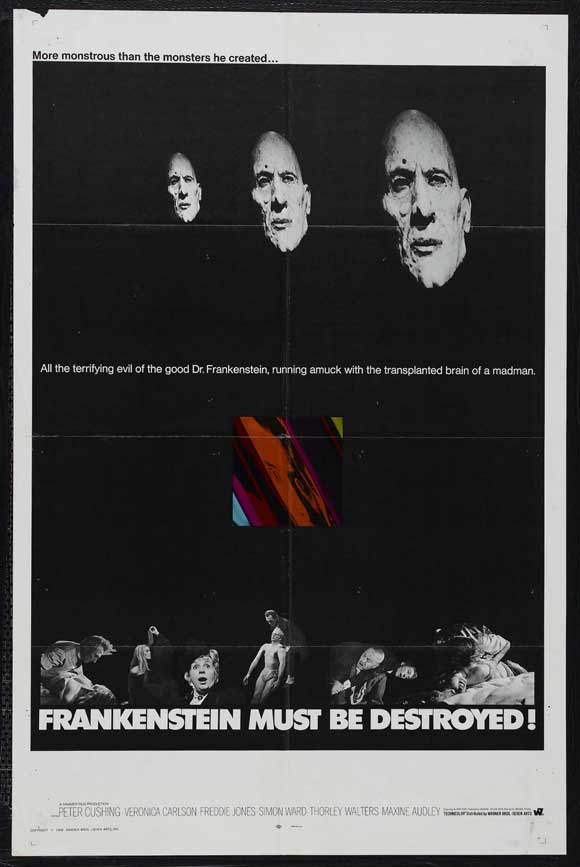

It’s a well kept secret that Hammer’s Frankenstein series (1957-1974) is a good deal more interesting than its more popular sibling, the Dracula series. The Dracula formula was straightforward, cemented by its third film, Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966): Christopher Lee is resurrected, he corrupts some innocents, he is killed; repeat. But with the Frankensteins, a decision was made to make Peter Cushing – Dr. Frankenstein – the recurring character, not his monster. This created a distinct break from the 1930’s-40’s Universal series, in which various horror icons would don the same bolt-necked makeup from one film to the next. As a result, Hammer’s Frankenstein films were liberated from the castle dungeon. They could be more imaginative, and – best of all – were anchored to the charisma of Hammer MVP Cushing. Cushing is simply compelling to watch, whether casually murdering in the interest of science in the breakout hit The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) – which launched the full-color, blood-spattered Hammer Gothics – or wearily condescending to a courtroom in Frankenstein Created Woman (1967). His character is fairly consistent: brilliant, arrogant, impatient with all the idiots around him. He is convinced that any crime he commits is justifiable, because his aims are far-reaching, world-changing; it isn’t his fault that the fools around him don’t share his vision, and he certainly isn’t going to waste his time trying to explain himself. But by the fifth entry, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), he has reverted to a ruthlessness and cruelty not seen since the original 1957 film. Most of this was the design of director Terence Fisher, who had directed all of the series’ previous chapters except for Freddie Francis’ Universal-style throwback The Evil of Frankenstein (1964). But one bit of nastiness was imposed upon him by Warner Brothers and Hammer head honcho James Carreras. He wanted nothing to do with it, and neither did his stars; more on that in a moment. Regardless, Fisher came to regard Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed as one of his personal favorites.

Peter Cushing makes a memorable, chilling entrance disguised by a sinister mask.

The film is also unique because it takes its time getting to what one commonly associates with Frankenstein films: a laboratory, some bloody tools, the dead coming to life. In fact, this happens about two-thirds of the way through the film. The opening sequence is a series of feints. First we hear Third Man-style zither music – composer James Bernard being clever – as Fisher’s camera cuts across empty nighttime streets. Then blood is splashed against a window: someone has been slaughtered. Elsewhere, a burglar tries to jimmy a lock, but he hears approaching footsteps and ducks inside an empty house. There he stumbles upon a Chamber of Horrors, including a frozen body suspended in a tank. A grotesquely disfigured man enters from the street. He places a container on the floor, out of which spills a severed head. The burglar barely escapes with his life, and the monstrous figure removes a mask to reveal – Peter Cushing. Indeed, this is the Frankenstein film in which Cushing finally becomes a monster, albeit by a gradual descent into immorality that has been ongoing for five films; in Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed we will see him at his most depraved. The burglar attracts the attention of the police, including an inspector who will be tracking the Baron for the remainder of the film – an amusingly annoyed Thorley Walters (Dracula: Prince of Darkness). Frankenstein, looking for a place to set up shop, decides to blackmail a young medical student, Karl (Simon Ward, If…), and his fiancée, Anna (Veronica Carlson, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave). Both of them share a secret: that Karl has been peddling stolen drugs to raise money for Anna’s ailing mother. Upon discovering this, Frankenstein uses it not just for free room and board, but to gain a new assistant for his experiments. As he tells Karl, “Your medical education is about to be vastly improved.”

Karl (Simon Ward), Baron Frankenstein (Cushing), and Anna (Veronica Carlson).

Gradually revealed is that the Baron has come to the village to retrieve the brilliant Dr. Brandt (George Pravda, Thunderball), with whom he was corresponding before Brandt went insane and was committed to an asylum. Before his unraveling, Brandt believed that it was possible to freeze a brain at the instant before death, then transplant it into another body, preserving the man’s intelligence. With the reluctant Karl, he steals into the asylum and together they kidnap Brandt. In the shock, the fragile Brandt suffers a heart attack – giving the Baron the perfect opportunity to test the man’s theory. He needs a vessel for Brandt’s brain. “Remember,” he patiently says to Karl, “Dr. Knox had Burke and Hare to assist him. Think what they did for surgery between them. Now I have you.” So Karl is persuaded to murder one Professor Richter (Freddie Jones, The Elephant Man). With the surgery complete, Brandt’s consciousness slowly stirs within Richter’s body. When, late in the film, he escapes Frankenstein, he wants only to reconnect with his wife (Maxine Audley, Peeping Tom) – but of course she doesn’t recognize him. Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed plays as a chain of hostage situations. The Baron keeps a tight hold on Karl and Anna through blackmail and power games; and Brandt isn’t above holding his own wife hostage while he locks down the house as a trap for the Baron. But the main focus of the film is on Karl and Anna, Frankenstein’s principal victims (the title might as well be This Young Couple Must Be Destroyed). After they are compelled to bury Brandt’s body in the garden, the next morning a water main bursts, and the corpse’s hand thrusts out of the soil and flops about in the fountain. Anna, the sole witness, is left to crawl into the wet mud, heft out the heavy body, and drag it out of sight. Her duty complete, she stands there sopping wet, shivering, her shock total, and when a woman offers to help her, she lashes out, “Go away! For God’s sake go away! Leave me alone!”

In a parlor, Baron Frankenstein listens in on the gossip of doctors.

Carlson gives an excellent performance as Anna, who – for a relatively minor sin (keeping her fiancé’s secret about the drugs) – is hauled into Frankenstein’s world of madness and murder. But her treatment at the hands of the Baron is particularly nauseating. In the film’s most notorious scene, the Baron rapes her in her bedroom while Karl is away. These are the pages that were forced into Fisher’s hands by a studio and distributor nervous about the edgier horror films making a splash on the market – the previous year saw both Rosemary’s Baby and Night of the Living Dead. And in the U.K., sexploitation was proving lucrative. Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed was one of Hammer’s last pictures before nudity became a requirement. Carlson had a no-nudity clause, but the rape was shocking nonetheless – in particular because it feels out of character for Frankenstein. Perhaps the young, depraved Baron of the 1957 film might have stooped this low, but the protagonist of the intervening films would not. Which means that we must read the rape as a power play, a way of putting Anna under his control. This is as dark as Hammer’s Frankenstein films ever got, and it came about because Fisher had to make do, his hand forced – another of the film’s hostages. In an August 2015 interview with Bruce G. Hallenbeck printed in Little Shoppe of Horrors #35, Carlson recalled that Fisher initially stormed off the set before they finally resigned themselves to filming the scene. “The more we tried to make it work, the worse it was and it just got grotesque. I was so miserable. And then, I remember, Roger Moore came from nowhere. He was on another sound stage. How he heard about it, I’ll never know. And he came over to comfort us both. He was reassuring me and patting Peter on the back. He understood the misery that we were in. And he knew the back-story of Frankenstein very well and knew that it should not be part of the film.” The Baron forcing Anna to submit to him sexually is only more stomach-turning in light of her ultimate fate, which is to be brutally stabbed by him after she threatens his creation. And by this point the audience will agree: yes, Frankenstein must be destroyed.

Publicity still: Freddie Jones carries Cushing back into a burning building.

Despite the film’s pitch-darkness, there are moments of humor, however fleeting. Walters is enjoyable as the requisite comic relief (though he ultimately has no effect on the story’s outcome). When Mrs. Brandt discovers Frankenstein, rather than flee he switches on the charm and welcomes him into his laboratory, insisting he was going to invite her to see her abducted husband when the time was right. “He is simply asleep,” he says, indicating the bandaged and disguised figure on the slab. “Asleep and sane. He is cured…There is no one else in the world who could help you but me. And that I have done.” Then he says, casually, “What is important is that you speak of this to no one. I have seriously broken the law.” And when he hits the word “seriously,” he laughs. Cushing can’t help it. It’s the only sensible way to deliver the understatement. As soon as Mrs. Brandt departs, calmed and smiling and grateful, Cushing shuts the door and declares to Karl and Anna, “Pack! We’re leaving.” In a movie this dark, these moments come across as welcome gallows humor. And they help enliven a film which is unusually slow moving for a 1969 Hammer movie. Fisher takes his time, focusing upon the characters instead of Gothic trappings. Interviewed by Harry Ringel in Cinefantastique Vol. 4, # 3, in 1975, Fisher said, “That was probably the first time within the Frankenstein series that you had a really emotional, character approach to brain transplants… And a brain with its own memory of a life which it has led, its loves and its hates. In the film…[Freddie Jones] goes to visit his wife who fails to recognize him and rejects him. I loved that subject, which I think was a most difficult one to portray, and I thought about that film more than any other I’ve done because of this element.”

Anna is stalked by Frankenstein’s latest creation (Jones).

Jones gives a touching performance despite his limited screen time. When he visits his wife, he stands behind a screen, ashamed of his appearance (shades of his later film The Elephant Man, where he played someone exploiting another’s freakishness). Mrs. Brandt awakens only to hear his voice coming from the screen. Only we can see that he has tears in his eyes. Nevertheless, trapped within the violent vortex that Frankenstein carries with him wherever he goes, he must do what he must do: destroy his home (literally and metaphorically) and the Baron with it. With all this rich thematic material, it’s only on reflection that I realize the plot doesn’t really make any sense: the Baron has already successfully frozen and transplanted a brain, proving Brandt’s theory; why does he still need to retrieve a “formula” for doing so? (Maybe I missed something. If I did, let me know in the comments.) Regardless, this is one of the best films of Hammer’s Frankensteins, and evidence that Cushing and Fisher were performing some fascinating experiments in the series. Hammer tried to “reboot” the franchise after this with Jimmy Sangster’s horror-comedy Horror of Frankenstein (1970) starring Ralph Bates, but Cushing and Fisher would reunite for a worthy closing chapter, Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974). Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed was released last month on Blu-Ray as part of Warner’s Horror Classics Volume One, alongside The Mummy (1959), Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968), and Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970). It looks exceptional in high definition, although, as with all the titles, there are no extras except a trailer.