Earlier this week my wife received an email from a mailing list, and she asked me, “Do you want to go see a 1915 version of Alice in Wonderland with live piano accompaniment by David Drazin at the Towne Cinema in Watertown, Wisconsin?” Yes, yes I would, no questions asked. So on Wednesday night, December 30th, we took the hour-long drive from Madison to Watertown, population 23,929. It’s the picture of small-town Wisconsin, the downtown district (Main Street, of course) consisting of very old buildings, eccentric establishments like a dairy bar and a cobbler mixed in among the taverns, and the centerpiece, the Towne Cinema itself, with its prominent glowing marquee. Built in 1913, it began as a theater showcasing vaudeville before eventually transitioning to a full-time cinema. In recent years, like so many struggling independent movie theaters, it had to raise funds quickly to meet the studio-imposed transition to digital projection. In this case, a successful Kickstarter campaign did the trick. They continue to show films at a fixed $4 price, and on the evening we visited, were balancing screenings of first-run films (Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Daddy’s Home, and the surely-will-be-talked-about-100-years-from-now Alvin and the Chipmunks: Road Chip) with a 1915 silent film directed by a gentleman who hailed from Monroe, Wisconsin, W.W. Young. So the event was as much about showing some Wisconsin pride as anything else. (Lest you roll your eyes, we also gave you Orson Welles, so you’re welcome.) The silent film was free, and the theater was full. Teenagers on dates. Elderly couples. Families with children. Film buff hipsters. Everyone – including the accomplished improv jazz pianist Drazin, who lives in Illinois but drives up frequently to Madison to accompany silent film screenings, and Young’s great great niece, Charlotte Groth, a local historian who conducted a post-film Q&A.

Marquee for the Dec. 30th screening at the Towne Cinema in Watertown, Wisconsin.

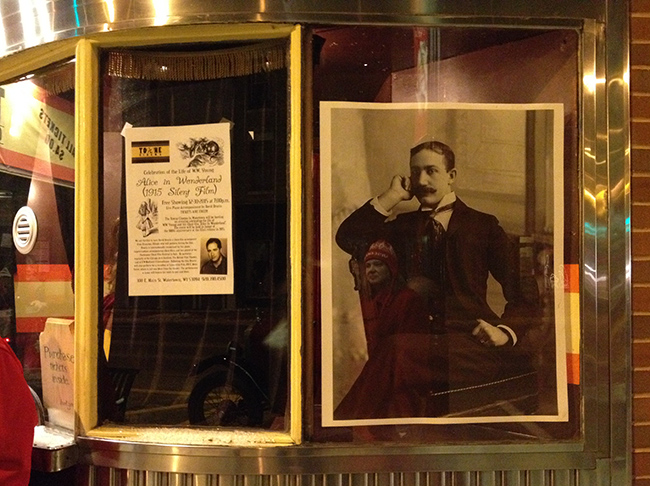

Despite its first-run titles, the Towne Cinema, with its handmade charms, is the perfect venue for a repertory screening. In the lobby, photos of W.W. Young, provided by the Wisconsin Historical Society, were on display, along with a Do Not Touch lightsaber prop and, for sale, some Star Wars-related paintings (I admired the Princess Leia portrait). Walking into the main theater, you pass an original poster for Tarzan and the Jungle Boy (1968), a wall of movie quotes, and two paintings of Karloff as Frankenstein’s monster and the Mummy, respectively. I prefer touches like this to the corporate-sanctioned flair of the multiplex: when I went to see Star Wars a few weeks ago, the boy tearing our ticket had a name tag that said, “My Favorite Movie is The Maze Runner.” The Towne Cinema, by contrast, is the sort of place where you make a point to buy popcorn and Junior Mints because you want them to stick around – and Alice in Wonderland was free, for God’s sake. Such was the enthusiasm for this little event that one man showed up in a tuxedo and top hat, parking his vintage vehicle out front to help set the atmosphere. The occasion was the 100th anniversary of W.W. Young’s Alice in Wonderland, and the 150th anniversary of Lewis Carroll’s original book, properly called Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Though Young lived in Monroe for a time, he became the Sunday editor of William Randolph Hearst’s Chicago American in Chicago, before moving to New York to write for The New York Sunday World and to become the head of the National Editorial Service of New York. He shot Alice in Wonderland in Central Park and other parts of New York state, and it is his only film other than The Mystery of Life (1931), a discussion on Evolution with Clarence Darrow and Professor H.M. Parshley.

Portrait of director W.W. Young outside the Towne Cinema.

Although Young didn’t leave a significant mark on cinema, by filming Carroll’s beloved book he at least guaranteed that his film would achieve a lasting interest. Alice fans, such as myself, will seek out anything related to Carroll. Young was actually the third to adapt the work, following a very early stab from 1903, and a 10-minute short from 1910. (You can read a good article on Alice adaptations from 1903-1966 at From the Bygone.) Young’s Alice is ambitious in scope, seeking to adapt all of Carroll’s book, even if it’s unaccomplished in style. Like a lot of early cinema, the film is rigidly stagy, presenting one stationary tableau after another with neither close-ups nor any sense of editing rhythm. Interstitial cards announce what we are about to see before we actually see it. D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, released the same year, would open the gates to a more dynamic style of cinema going forward, but you won’t see any evidence of that here. As for special effects, Young usually doesn’t bother, the main exception being a Cheshire Cat that vanishes, reappears, and vanishes again, eventually leaving just his head. There’s a touch of Méliès to the scene, but more clumsily handled – obviously, Méliès, through his hundreds of films, quickly developed more experience with trick editing and FX. Young was a neophyte, just eager to get his hands on a camera and to make something, figuring things out along the way as best he can. Where he excels is the costuming. His Alice in Wonderland pays close attention to the famous illustrations by John Tenniel and seeks to replicate them as closely as possible, posing his actors in the same positions as the characters in Tenniel’s panels, and modeling the costumes and masks on Tenniel’s big-headed caricatures. Something similar was done in Paramount’s 1933 Alice in Wonderland, but those masks, by the legendary Wally Westmore, are as grotesque and disturbing as they are impressively designed (mind you, this is one of the principal reasons to see that film – it’s a trip). One of my favorite Alice chapters, “Pig and Pepper,” featuring an ugly, child-beating Duchess, a pepper-flinging cook, and the Cheshire Cat, is convincingly rendered in Young’s hands, and the moment where Alice finds that her rescued child has transformed into a pig elicited genuine surprise from those members of the audience less familiar with the original book. (Admittedly, Young’s awkward staging of the transformation makes the scene a bit more surreal than intended.) Excellent creature costumes include the Dodo Bird (who holds a cane with a human hand, just as in Tenniel’s illustration), the White Rabbit, a Caterpillar who descends from his mushroom to crawl along the ground, and, in the film’s best dose of fantasy imagery, a seaside landscape featuring a floppy-clawed Gryphon, a Mock Turtle singing about turtle soup, some walruses with parasols, and giant lobsters crawling out of the ocean in a shot straight out of some 50’s Roger Corman monster movie.

Alice (Viola Savoy) meets the Duchess, the Cook, and the Cheshire Cat.

The print in circulation – and available on YouTube – appears to be incomplete. (The screening was projected from a version released on DVD.) The Mad Hatter’s Tea Party is not shown, but I have a hard time believing Young wouldn’t have filmed it, since he includes such moments as “Pig and Pepper” and a scrupulously faithful recitation of the “Father William” poem (including Father William balancing an eel on his nose). The Mad Hatter and Dormouse do make an appearance in the Queen of Hearts’ courtroom, so you can at least imagine what the scene would have looked like. I can be more certain that we’re missing a scene of Humpty Dumpty, since the character is prominently featured on the film’s poster. Given the modest scale of the film, it’s doubtful we’re missing anything that would change one’s opinion of it: it’s a quaint little movie, a footnote in the history of Alice adaptations, but it has charm – not unlike the children’s films produced by L. Frank Baum’s Oz Films. At the December 30th screening, the audience indulged the film’s limitations, laughed (and, in one case, audibly groaned) at the jokes, and generously applauded David Drazin, whose improvised piano performance at a few points had to soldier on through DVD playback glitches. Then he was off to wheel the piano up the street to play a jazz set at the Irish pub, while the crowd milled about in the lobby to look at old photos of W.W. Young, or to examine the vintage auto parked outside. I can’t imagine anyone ever congregating again in like fashion and for such a forgotten, modest little film; it was a surreal small-town moment done and gone.

Note 12/31/15: This post has been corrected to state that W.W. Young was from Monroe, WI – my original article stated Monona. Thanks to Eileen Worman for the correction.