Anthony Newley (1931-1999) was a British singer, songwriter, and actor best known for writing songs like “Feeling Good,” “Goldfinger,” and the score to Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971). With his crooning voice and mammoth twitching eyebrows, he became a popular performer with hits like “Personality,” and appeared frequently on television and on the stage (notably in his musical Stop the World – I Want to Get Off). He also appeared in the 1967 musical Doctor Doolittle, and while enduring a protracted, troubled production shoot, and allegedly anti-Semitic abuse from star Rex Harrison, the frustrated Newley began to conceive his own project, a semi-autobiographical movie musical that would be more audacious than anything in Doolittle. The story would be a thinly veiled autobiography (the best kind), covering such matters as his stratospheric rise as a pop performer, the death of his first child, his failed marriages, and his womanizing. He composed the music with lyricist Herbert Kretzmer, who had written the novelty song “Goodness Gracious Me” for Sophia Loren and Peter Sellers (Kretzmer’s greatest success would come much later with his contributions to Les Misérables). The proposed film was a vanity project, but a self-conscious one, commenting constantly on the main character’s selfishness and libido. Universal finally agreed to back the film with Newley as its star, co-writer, composer, producer, and director. It was a British film, produced by Universal’s British subsidiary, and released in 1969 with an edgy X rating. This was the period when Hollywood was beginning to admit it didn’t know what audiences wanted anymore, but adult entertainment was a strong bet. United Artists would win the Oscar for Best Picture for that year’s X-rated Midnight Cowboy. Elsewhere, Fox was about to hand its keys to Russ Meyer, who had scored an independent hit with his X-rated Vixen! (1968); he delivered Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) – though he later said he would have made it racier if he’d known it was going out with an X. Warner Bros. was to release the X-rated Sidney Lumet film Last of the Mobile Hot Shots (1970), with a script by Gore Vidal. Newley’s film was stamped with an X rating and given the indigestible title Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe and Find True Happiness? What I wouldn’t give to have worked the ticket booth the weekend that was released; free popcorn to those who get the title right. I imagine most would just say, “The nudie musical, please.”

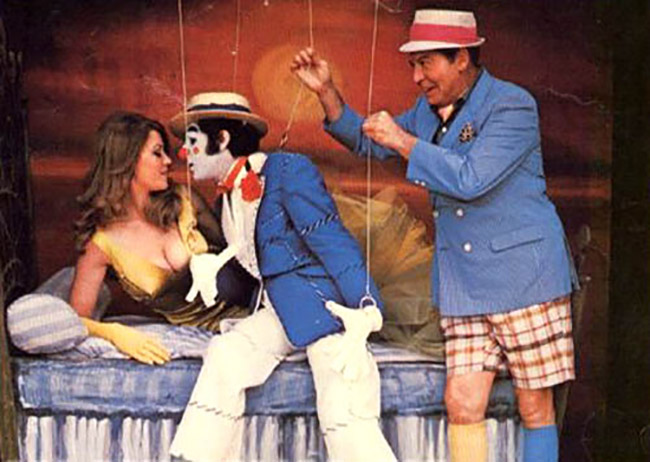

Anthony Newley as Heironymus Merkin, Joan Collins as Polyester Poontang.

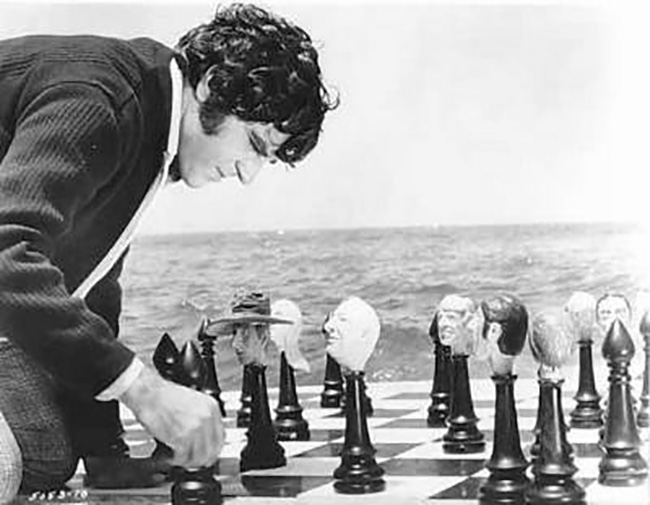

Newley plays Heironymus Merkin, first seen sitting on a beach before a vast collection of his personal belongings. Having just celebrated his fortieth birthday, he calls the assemblage “a monument to my first 40 years.” He wears gigantic sunglasses and leans upon a film projector while delivering his monologue to a captive audience – the spellbound, admiring mother (Patricia Hayes, A Fish Called Wanda) and his two small children, Thumbelina and Thaxted (played by Newley’s children Tara and Alexander). This beach, shot on location in Malta, becomes the main setting of the film, like a Beckett play, with many surreal scenes impressively staged against the backdrop of cliffs and crashing waves. At one point, a line of women snake down the sands toward Merkin’s waiting bed; later, when he marries his first wife Filigree Fondle (Judy Cornwell, Whoever Slew Auntie Roo?), the beach becomes the setting of a Catholic church without walls, its three stained glass windows suspended in the air. As a director, Newley excels at conjuring such striking visuals. A flashback to his childhood shows his uncle, a stage performer operating under the name Poindexter Limelight (Bruce Forsyth, Bedknobs and Broomsticks), playing a giant piano while wearing stilts, an image which surely influenced the Elton John appearance in Ken Russell’s Tommy (1975). (With its music, sex, and surrealism, Merkin is reminiscent of Russell’s entire oeuvre.) Merkin is screening footage from a film he’s made about his own life, a film that’s not yet finished. As day drags into night, he’s joined by a film crew led by another director, also played by Newley. Merkin’s writers and producers agonize over the film’s lack of commercial appeal. A trio of critics deride the film as pornography, and mention that Fellini has done all this before, and better. Occasionally a figure called The Presence appears to torment Merkin with parables of death – actually just bad Borscht Belt jokes delivered by vaudeville comedian George Jessel in a white suit and a parasol in his hand.

Heironymus Merkin plays chess with the figures from his past.

Merkin begins his career as a child performer wearing clown makeup and operated by marionette strings. As a young adult, he’s introduced to the pleasures of women by an apparition named Goodtime Eddie Filth, played by none other than Uncle Miltie himself, comedian Milton Berle (It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World), and who first appears in elaborate goat make-up, having just arrived from Hell. (Later in the film Berle hosts a Satanic ceremony, dressed in a red cloak and hovering over one of the film’s many naked blondes.) Berle materializes the eye-popping Margaret Nolan of Goldfinger (1964) and various men’s magazines. “She has a very small mind,” Berle admits, and as the camera focuses on her breasts, he adds, “but the rest of her is very intelligent.” Scoring a hit with the cabaret-style “Piccadilly Lilly,” Merkin spends his free time bedding admiring fans (female or male – but mostly female). Amidst the sex, Newley sprinkles some artistic pretentiousness by linking his character with the Harlequin from Commedia del’arte, often wearing the iconic checkered costume; he even performs a musical number in a Commedia del’arte play, which is technically a play-within-a-film-within-a-film-within-a-I lost count. It’s during this performance that he meets Polyester Poontang, played by his then-wife Joan Collins. Polyester is sophisticated and sees right through him; after they’re married, she doesn’t seem to mind terribly that he has flings on the side. Collins even gets a Horoscope-themed musical number. While costumed dancers representing the signs of the Zodiac spin about her, she sings to a naked Newley, “I’m a fool maybe, but I don’t mind chalk with my cheese.” (The song is called “Chalk & Cheese.”) Another musical number, “Once Upon a Time,” is devoted to a dirty joke about a large-breasted princess and her love affair with a donkey. It has nothing to do with the plot, but you won’t forget it. During one sex scene, Merkin substitutes a life-size, wind-up sex doll, which has no eyes, although the mouth occasionally becomes a cartoon that spouts word balloons on the screen.

The cover image of the soundtrack depicts Merkin with his “nymphet” Mercy Humppe (Connie Kreski).

The abundant female nudity and the cheeky, politically incorrect jokes, make it abundantly clear why this film’s biggest fan seems to have been Playboy Magazine – posters for the film boasted the magazine’s 10-page spread on Merkin. This is really a “men’s film,” like a nudie magazine interspersed with serious articles that might be of interest to men, such as how many women Anthony Newley has bedded. The Mercy Humppe of the title is played by Playmate Connie Kreski. She arrives late in the film, but memorably, astride a pink pig in a merry-go-round like a Terry Gilliam animation come to life. Leading up to this revelation, the on-screen writers and producers have pleaded with Merkin to please, please skip the Mercy Humppe section – but Merkin sees Humppe as the pivotal moment of his life. Having divided his film into chapters, he calls this one, “The Dream of Humbert Humbert, or Snow White Meets Attila the Hun.” With the Lolita reference made explicit, he calls Mercy his nymphet, and quite openly discusses his obsession with young girls to his own daughter, in what is easily the film’s most uncomfortable scene. (Well, that and the underwater, LSD-tinged oral sex scene with Kreski.) As Humppe is unveiled, one of the film critics, played by the always-wonderful Victor Spinetti (A Hard Day’s Night), gasps, “Oh my good God, it’s Captain Child Molester!” It’s one of the film’s many great one-liners, such as the moment Merkin turns to his daughter and explains, “Grandma’s crying because she doesn’t understand the cyclone that came out of her womb.” Ultimately Merkin abandons Humppe, just as he does all the women in his life; she’s devastated by his marriage to Polyester. It’s a bit difficult for the audience to find much sympathy for such a loathsome, self-absorbed character, but Newley beats us to the condemnation; in one of the film’s last scenes, he comes to the realization that he’s a misogynist. He’s also abandoned by Polyester, who takes his children and leaves him alone on the beach – this, shortly after Newley has sung an upbeat number about how we’re all alone in the world and there is no God. As one of the writers laments, “Fade out on producers and writers not understanding and not having an ending.” So Newley delivers his happy ending: ending credits in which all the performers step onstage to smile and bow for the audience, Brewster McCloud style. Is Merkin a good film? Not exactly, but it’s not the disaster its premise suggests. Its principal flaw is that Merkin’s life isn’t terrible interesting – his bio amounts to little more than callous womanizing. The fact that Newley’s a quick wit, a talented showman, and a surprisingly capable director make the film entertaining, and take the premise much further than it should: there’s something diverting, even jaw-dropping, every few minutes. UW-Madison’s Cinematheque screened a decent-looking 35mm print last Friday night, but the opening Universal logo easily explains why the film’s home video distribution is limited to poor-quality bootlegs: Universal is notoriously stingy with its back catalog (if Warner had this, it would have released it via its Warner Archive imprint years ago). A shame, because Heironymus Merkin, with its wild sights and aggressive conviction, would be welcomed by fans of one-of-a-kind cinema.