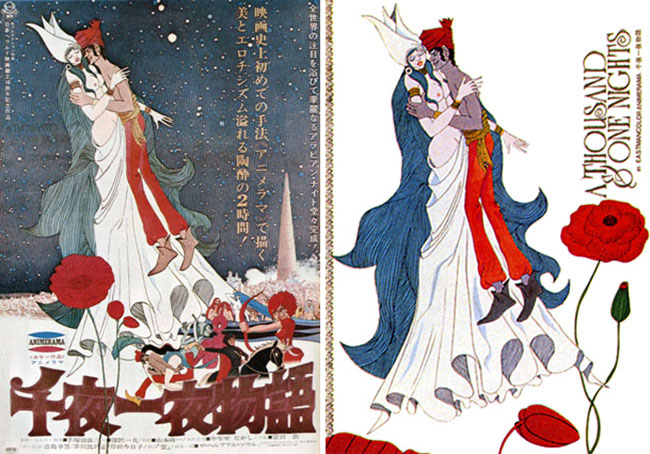

Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat (1972) may have been the first X-rated animated film, but three years before its release Japan had already begun testing the boundaries of adult animation with A Thousand and One Nights (Sen’ya ichiya monogatari, aka One Thousand and One Nights, aka Arabian Nights; 1969). The film sprung from the imagination of Osamu Tezuka, the Walt Disney of Japan, creator of the manga series Astro Boy, Kimba the White Lion, Metropolis, Buddha, and Phoenix, among others. He was the head of the animation studio Mushi Productions, which helped define anime with its adaptations of Astro Boy and Kimba. The success of the studio gave Tezuka the confidence to embark on animated feature films intended expressly for adult audiences. The first, A Thousand and One Nights – inspired by Tezuka’s own manga adaptations of Arabian Nights – would initiate a trilogy the studio called “Animerama,” distinguishing their intentions from children’s cartoons. The subsequent films were Cleopatra: Queen of Sex (1970) and Belladonna of Sadness (1973). Tezuka was the co-director of the first two films in the series, partnering with Eiichi Yamamoto, who would later direct the seminal series Space Battleship Yamato. (Yamamoto helmed Belladonna of Sadness on his own.) All three films are overtly erotic. In A Thousand and One Nights, most of the female characters are consistently unclothed.

Aladdin is united with the slave girl Miriam.

At the pre-credits sequence we already know we’re in for a very different kind of animated film. To the sound of garage rock and poorly enunciated English lyrics – “Al-din, Al-din, here comes a man called Al-din!” – we’re introduced to a smiling Aladdin strutting through a heat-hazy, black-and-white desert. He’s almost walking with an R. Crumb Keep on Truckin’ stride; in fact, in many of the early sequences I was reminded not of Japanese manga but 60’s San Francisco underground comix, one of several ways the film anticipates Bakshi’s 70’s films. He arrives at Baghdad and soon falls for a beautiful, large-eyed girl being sold in a slave market, Miriam. Just as Havaslakum, the spoiled son of the captain of the guard, purchases Miriam, a dust devil sweeps out of the desert and into Baghdad. Aladdin takes the opportunity to steal away with the girl. They consummate their love in a scene which substitutes pornography with symbolism: a slow pan down Miriam’s navel cuts to a budding rose, and we dive down a red tunnel in its blossom, a gyno-floral sequence reminiscent of the sexual animated scene in Pink Floyd The Wall (1982), minus the toxic misogyny. Afterward, they learn the house into which they’ve broken belongs to the wealthy Suleiman, who locks them inside so he can watch their couplings for his own pleasure. When Havaslakum discovers that Suleiman is holding Miriam, he persuades his father, the captain of the guard, and his father’s assistant, the scheming Badli, to bring down Suleiman. Badli rides into the desert and meets with the leader of the Forty Thieves, who reside in a cave that can only be opened by saying “Open Sesame” (or, in this Japanese rendition, “Open Gingili”). The thieves are portrayed in the broadest of caricatures, fighting each other and gang-banging a girl in a scene that looks like Bakshi drew it himself. The chief of the bandits has a red-haired daughter, Madhya, who possesses a fiery temper and walks about with one breast exposed and one covered, like an Amazonian. After Badli persuades the thieves to attack Suleiman’s mansion, he corners Madhya in a field and rapes her. She swears she will have her revenge. The bandits follow through on their assault, killing Suleiman in the process, and Miriam and Aladdin are seized by the Baghdad guard. Aladdin is accused of murdering Suleiman and tortured (with a pendulum blade straight out of “The Pit and the Pendulum”). He escapes and discovers the lair of the Forty Thieves where he dives Scrooge McDuck-style into a pile of stolen gold. He meets Madhya, and they escape together riding a magical flying hobby horse in the shape of a unicorn. Back in Baghdad, Miriam dies while gives birth to a daughter.

A Rukh attacks Aladdin’s ship.

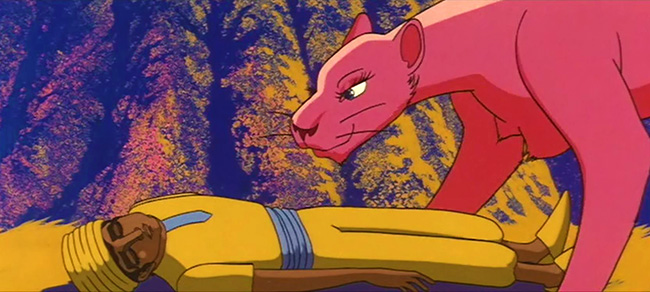

Aladdin and Mahdya crash on a snake-shaped island, brought down by what at first appear to be blue tentacles. We learn they are the long tresses of one of the island’s inhabitants, a collective of nude, siren-like women lounging on the beach. Aladdin, transfixed with lust, wishes to stay, and the heartbroken Mahdya departs on her flying unicorn. A pair of intensely stylized sex scenes follow, remarkable hand-drawn animation in which abstract lines and shapes resolve themselves into merging and penetrating bodies. Between these avant-garde sex sessions, Aladdin eats fruit from an erotically-shaped tree at the behest of a smiling serpent, and later he spies upon his lover, the mistress of the island, turning into that very snake. Discovered, she attacks Aladdin, and he’s pursued by all the women, who reveal themselves to be more serpents (one of whom is in the act of consuming another). He takes refuge on a ship, but it’s attacked by a giant Rukh. The ship’s crew come to another island which is occupied by a three-eyed giant. The Rukh attacks the giant in a sort of Ray Harryhausen tussle, and Aladdin flees, taking shelter inside a wish-granting ship. By the time he arrives back in Baghdad – fifteen years later – he possesses a wealthy fleet and many servants, and operates under the alias Sinbad. More characters are introduced for the lengthy final act, including two small, lusty, shape-changing djinn, who ride a magic carpet, and decide to intervene in the lives of a young couple named Aslan and Yahliz. The two fall in love thanks to the djinn, but Yahliz is under the protection of the evil Badli, who wishes for her to marry the sultan. When Sinbad/Aladdin arrives, Badli and the sultan, jealous of his wealth and power, plot to destroy him. This leads to a contest, set in an arena, in which the sultan and Sinbad compare their wealth; at one point they even produce a golden and bejeweled automobile and television set. Aladdin loses the contest but tricks the sultan into boarding the wish-granting ship, which Aladdin orders to sail to the end of the world. With the sultan gone, Aladdin appoints himself the ruler of Baghdad. He immediately takes an interest in Yahliz, struck by her resemblance to Miriam – unaware that she is actually his own daughter. Power mad, Aladdin orders the erection of a great tower (resembling the Tower of Babel), so high, he demands, that it must touch the sun. Its construction drains Baghdad’s resources and threatens to topple onto the city. Eager to undo Sinbad, Badli reveals before the royal court that Yahliz is Aladdin’s daughter, and accuses him of incest – but Aslan, Yahliz’s lover, declares that Aladdin never consummated his infatuation, for the night Aladdin tried to seduce Yahliz, she found herself in Aslan’s arms instead. Finally, Mahdya arrives to take revenge on Badli, killing him, and Aladdin, removed from the throne, finds himself back in the desert, walking away happily as his psych-rock theme plays on the soundtrack.

The sultan’s mechanical swordsman.

The animation of A Thousand and One Nights is varied, not fitting neatly into the expected anime style. Aladdin has a big nose, and his physical movements occasionally call to mind old Popeye cartoons. Miriam and Yahliz are drawn in an altogether different style, influenced, it seems, by Persian art. The erotic scenes seem to excite the imagination of Tezuka and Yamamoto the most, in particular the island of serpent women, which plays like a dazzling stream-of-consciousness experiment, and reminds us of what we lose when animation isn’t produced by human hand one cel at a time. (Keep an eye out for a Tezuka gag when panning across the rubble of Aladdin’s tower: one of the bricks says “Made in Japan.”) Some of the backgrounds, particularly in Baghdad, might remind animation buffs of Richard Williams’ unfinished would-be masterpiece The Thief and the Cobbler, though it’s not quite as dexterous or ambitious in style (what is?). The film is also notable for combining animation with live action. Some of the ocean scenes are depicted with the animated characters looking out on a real ocean, and other shots, such as Aladdin’s tower and some of the cupolas of Baghdad, involve colorful and detailed miniatures. Other moments are told in still frames, forming a layout on the screen like a page from Tezuka’s manga. The soundtrack is a hodgepodge of rock ‘n’ roll, classical music (including Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scheherazade”), and the film’s composer, frequent Tezuka collaborator Isao Tomita. But the achievement of the film is the sum of its parts. At 130 minutes, and telling not just one story but many connecting stories in tribute to the ancient Arabian Nights, the film has the feel of an animated epic. Its commitment to retaining the sexual frankness of the original text, from overt eroticism to the mere admission of such concepts as rape, pregnancy, and childbirth, staked out new ground for animated cinema, even though the film barely screened in the West.