Blasted out of the Arctic ice with atomic testing is a prehistoric creature called the Rhedosaurus, scaly, spiny, and massive jawed, stomping on four legs, and sending a scientist toppling over a ridge. Later that man, Thomas Nesbitt (Paul Hubschmid, aka Paul Christian, The Indian Tomb), tries in vain to convince others that what he saw was real – and that the creature just witnessed off the waters of Nova Scotia is the same beast, swimming southward. Eventually he gains support from a young paleontologist, Lee Hunter (Paula Raymond, Devil’s Doorway), who sees the alarm on his face when he recognizes the creature in her collection of dinosaur sketches. He convinces her that if the Canadian witness identifies the same drawing, it would be evidence that the prehistoric behemoth is real. When the witness does indeed corroborate, they take their case to her mentor, paleontologist Thurgood Elson (Cecil Kellaway, Harvey), who is able to persuade a skeptical Col. Jack Evans (Kenneth Tobey, The Thing From Another World, It Came From Beneath the Sea) to support an expedition to find the creature, whom Elson is convinced is headed to the Hudson River, the only spot where Rhedosaurus fossils have been found. In a diving bell in shadowy submerged canyons, Professor Elson finally discovers The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) – right before it swallows him.

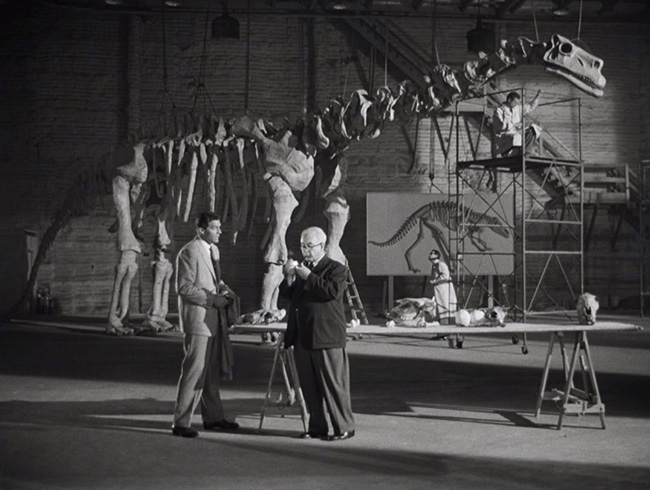

Prof. Thomas Nesbitt (Paul Hubschmid) describes the Rhedosaurus to Prof. Thurgood Elson (Cecil Kellaway). The skeleton in the background was borrowed from “Bringing Up Baby.”

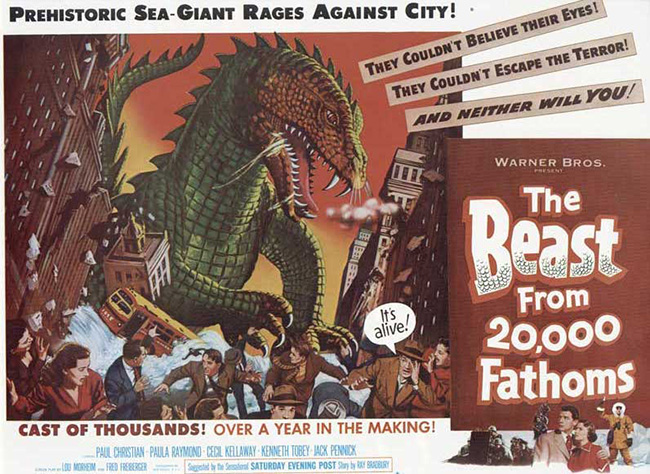

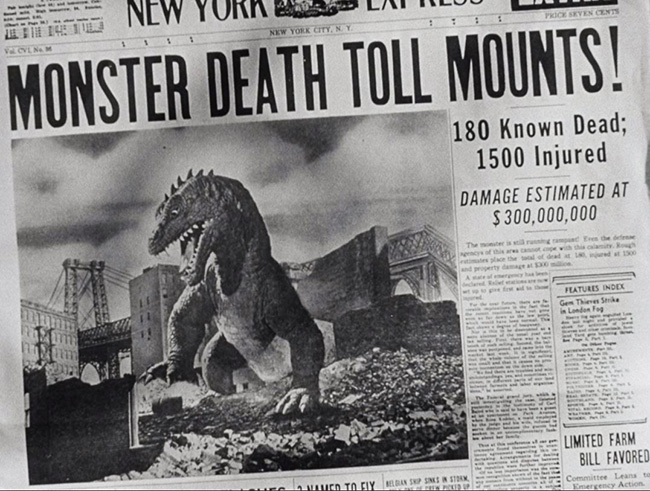

The special effects-driven Beast became the breakthrough film for Ray Harryhausen, who had previously created stop motion animation and other effects for the stellar Mighty Joe Young (1949) with his idol and mentor Willis O’Brien (King Kong). Beast is often credited with kicking off the cycle of Atom Age monster movies, preceding Godzilla (1954) – which would bring a more somber take on the effects of radiation – as well as Them! (1954), Tarantula (1955), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), and all the rest. It’s also a damn good example of the genre, one of the best. Here you will see the stock characters which will recur in so many later films – square jawed hero, female scientist, egghead professor. That all these characters are likable goes a long way. You also get a destructive finale in an iconic location – Coney Island, in this case. (Later Harryhausen films of the 50’s would deliver climaxes in Rome’s Colosseum and San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.) Unfortunately the film also features a newsreel-style narrator explaining events while we watch them in the opening scenes, a dated technique to add “realism” that was popular in SF films (and crime movies) of the decade; a modern viewer will just find it a weakness in screenwriting. And stock footage – another unfortunate staple – is abundant, but one shouldn’t expect less from a 50’s B-movie. The final attempt to bring down the monster, in which scientists dressed in radiation suits board a roller coaster, looks like a satirical moment from Brazil. But Beast delivers where it really matters – high quality special effects, respectful (if clumsy) attempts at delivering science, and moments of genuine thrills.

Prof. Elson dives deep to uncover the Rhedosaurus.

The following year, Them! would provide nail-biting tension through its masterful use of silence – without bombastic music cramming the soundtrack, the audience anticipates the tell-tale chitter of the giant ants; the calm before the storm. Silence was put to similar effect in the earlier The Thing from Another World (1951). On this recent viewing of Beast I was impressed that director Eugène Lourié (a noted art director from French cinema who had worked on Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion) also uses the quiet to elevate suspense. This is first evident in the initial Arctic encounter with the Rhedosaurus, but recurs in the aforementioned diving bell exploration of Kellaway’s Prof. Elson. Elson is delighted to be exploring the watery depths – we’re treated to a shark vs. octopus battle – and his delight only increases with the appearance of the creature he’s been seeking. He resists raising the diving bell, and realizes his mistake too late, as the creature zeroes in on his fragile sphere, the mouth opening toward the camera. I remembered this as being one of the best scenes in the film, but had forgotten that Lourié and screenwriters Lou Morheim and Fred Freiberger actually had the nerve to kill off such an appealing character.

The Rhedosaurus assaults a lighthouse.

The beast itself is the big attraction, and of course it looks great, even though the design isn’t quite as interesting as, say, the Ymir from 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) or the Cyclops from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958). (Actually, the fictional Rhedosaurus looks more like Sinbad’s dragon than an actual dinosaur.) Its bestial design also leaves little room for the trademark Harryhausen empathy, though we still feel a little sorry for it, since it’s just following its evolutionary function, an orphan trying to find other Rhedosauruses and confused by the modern civilization surrounding it. Its fate at Coney Island, crashing through the middle of the Cyclone Racer roller coaster, is a visual highlight, but so is the more lyrical image of the creature rearing up in silhouette before a lighthouse – an image drawn from Ray Bradbury’s short story, “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms” (later anthologized as “The Fog Horn”). As the story goes, the treatment for the film was presented to Harryhausen, who recognized elements from his friend Bradbury’s story; the chagrined producers sought out the story’s rights. Therefore this film marks a rare collaboration of sorts between the two famed Rays, both of them avowed dinosaur and King Kong buffs. It’s essential monster movie viewing, and fortunately is available on a Blu-Ray box set from Warner Bros., the Special Effects Collection, appropriately matched with Mighty Joe Young, Them!, and Son of Kong (1933).