An often overlooked entry in the renowned Val Lewton cycle of atmospheric chillers for RKO, Isle of the Dead (1945) is one of three films Lewton made with Boris Karloff, who, typecast despite his diverse acting talents, was a fugitive from Universal’s fun yet increasingly juvenile monster mashes. With Lewton he had an opportunity to showcase his acting chops free of monster makeup or a mad scientist’s white coat. Where else but in Lewton’s hands could Karloff play such a complicated character as Nikolas Pherides, a Greek general during the 1912 Balkan Wars. Nickname the “Watchdog,” his grim, unsympathetic style is on display at the start of the film, commanding an officer to shoot himself for the crime of allowing one of his units to arrive to the battlefield late. But as we get to know General Pherides through the eyes of audience surrogate Oliver Davis (Marc Cramer, The Canterville Ghost), an American reporter, we begin to see him as something of a broken man, just trying to do right by his particular sense of nationalism and justice. Pherides decides to visit the crypt of his wife on a nearby island, and Davis joins him, but they find the tomb violated, the body destroyed. A siren-like voice whispers through the trees and stark rocks, and following it, the two discover an Old Dark House and a gathering of strangers. An old woman in the home, Madame Kyra (Helene Thimig, Cloak and Dagger), warns that there is a vorvolaka on the loose, the Greek equivalent of a vampire – pointing the finger at a young woman named Thea (Ellen Drew, Christmas in July), whose beauty seems to flourish while a plague spreads throughout the house.

A statue of the three-headed dog of the Underworld, Cerberus, overlooks the pier on the Isle of the Dead.

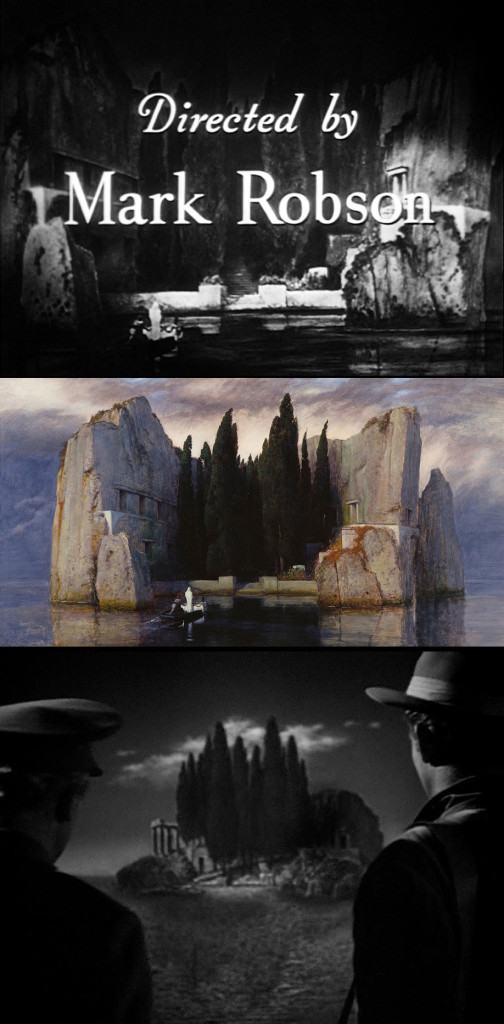

Isle of the Dead was directed by Mark Robson, who also directed for producer Lewton The Ghost Ship (1943), Youth Runs Wild (1944), and two genuine horror masterpieces, The Seventh Victim (1943) and Bedlam (1946, with Karloff). Post-Lewton, Robson would go on to a robust directing career: his credits include Peyton Place (1957), The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958), From the Terrace (1960), Von Ryan’s Express (1965), Valley of the Dolls (1967), and Earthquake (1974), among many others. Robson was adept at creating the suffocatingly macabre atmosphere that Lewton demanded – as with The Seventh Victim, Isle of the Dead and its cast of characters are obsessed with death; they are like zombies that haven’t had a chance to visit the grave yet, which perfectly sets up the film’s final act. Screenwriter Ardel Wray (The Leopard Man) had the unenviable task of adapting not a novel but a painting. The film is based on Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin’s famous series of images known as “Isle of the Dead” (1880-1886). One of these pictures previously appeared in a Jacques Tourneur film for Lewton, I Walked with a Zombie (1943, also written by Wray), and here is featured as a backdrop for the opening credits. It is also adapted into a matte painting, briefly glimpsed as General Pherides and Oliver Davis take their boat to the Greek island, Karloff like the ferryman Charon guiding Davis’s doomed soul. This is a common interpretation of the ferryman in the Böcklin painting, and it’s given extra emphasis in Robson’s film, with a statue of three-headed Cerberus – a snake around its neck – awaiting them at the island’s dock.

Three Isles of the Dead: the film’s opening credits; one of the original 19th century paintings by Arnold Böcklin; Boris Karloff and Marc Cramer ride a boat to the island in a scene from the film.

But this is not a literal Underworld, only a metaphorical one, and the structure of the rest of the film shares traits with a locked room mystery. It’s one of the talkiest of the Lewton series. People are dying, but it is almost certainly the plague, not the vorvolaka to which Madame Kyra refers. In his skepticism, General Pherides is joined by Dr. Drossos (Ernst Deutsch, The Third Man). Pherides quarantines the island, but soon Drossos himself succumbs to the plague. Davis falls for Thea, who is caring for the ill Mary (Katherine Emery, The Maze), the wife to a diplomat, St. Aubyn (Alan Napier, Alfred to the TV Batman). St. Aubyn also dies, while Kyra continues to finger Thea as the supernatural culprit. Also in residence is a Swiss archaeologist, Albrecht (Jason Robards Sr., Bedlam), who blames himself for uncovering the island’s tombs which were subsequently robbed by the same peasants who disturbed the grave of Pherides’ wife. As the deaths pile up, the general’s staunch skepticism begins to erode, and in secret he makes a sacrifice to Hermes to protect them from the vorvolaka – but he, too, begins to grow ill. There is a parallel here to what was happening behind the scenes. Shooting had to halt when Karloff required back surgery (Karloff had lifelong back problems); when he returned, the cast and crew had moved on, and so Lewton enlisted him for the Robert Louis Stevenson story The Body Snatcher (1945) instead, teaming him once more with Bela Lugosi. Then production on Isle of the Dead resumed. Karloff looks frail, gaunt, and downright haunted – appropriate for the story, bringing something vital to it.

Thea (Ellen Drew) pursues strange noises coming from a tomb.

Actual chills are late in coming, but potent when they arrive. Martin Scorsese listed the film as one of the scariest films of all time in a story for The Daily Beast: “There’s a moment…that never fails to scare me. Let’s just say that it involves premature burial.” Well, it’s not exactly The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, but it’s true that Isle of the Dead delivers the creeps just when it counts the most. After a solid hour of talking and not quite as much dread as one would hope from a Lewton picture like this, Robson suddenly ratchets up the tension following the burial of Mrs. St. Aubyn. The widow is a cataleptic and previously expressed a recurring nightmare of premature burial. Of course this occurs, in a plot twist straight out of Edgar Allan Poe. But Robson has the Val Lewton playbook, which means silence as deep as the shadows enveloping the screen, an eerie moaning, and fleeting glimpses of Mrs. St. Aubyn, gone mad, flitting across the screen. At one point she procures a trident of Poseidon, which she uses as an effective murder weapon. General Pherides, weak from the plague, stumbles through the dark toward Thea, convinced now that she is the vorvolaka, unaware that a real undead killer now stalks through the house. Isle of the Dead benefits from a crackerjack final fifteen minutes, but the build-up takes its sweet time, not always communicating precisely what the stakes are. With such an absence of visual evidence, we don’t really believe in the vorvolaka, which is a miscalculation on the part of the filmmakers. Nonetheless, part of what makes the Lewton films so special is the feel of risky experimentation with genre convention; if Isle of the Dead doesn’t entirely work, one nonetheless appreciates that Robson, Lewton and Wray are attempting to break from the usual rules, to emphasize character development and the themes at play: of modern day science vs. primal fears; of the responsibility of the living to the dead; of the blurry line between life and death. Isle of the Dead almost makes more sense as another chapter in a continuing thesis that runs through the Lewton thrillers, but regardless, it’s a genuinely haunting film that lingers after the ending credits.