Cry of the Banshee (1970) opens with a quote from Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Bells,” and his name was featured prominently in the advertising, despite the fact that the film is not an adaptation of Poe at all – but this was business as usual for American International Pictures. Call it Poesploitation. Gordon Hessler (The Golden Voyage of Sinbad), who worked with Alfred Hitchcock on Alfred Hitchcock Presents, was assigned to direct after proving himself to AIP with the box office successes of The Oblong Box (1969) and Scream and Scream Again (1970). As with those films, Hessler was teamed with star Vincent Price, and he brought along his favored screenwriter, Christopher Wicking, to help revise the original screenplay by Tim Kelly (Sugar Hill). (Wicking would soon make his mark in the world of Hammer horror, with Demons of the Mind, Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb, and To the Devil a Daughter.) The story had plenty of stock elements of late 60’s/early 70’s Gothic horror: sadistic tortures and executions of women accused of being witches; Satanism; a hypocritical ruling class; young love in rebellion; and of course gratuitous nudity and violence. Hessler’s cut of the film was censored in-house; AIP brought it down to a “GP” and removed the (abundant) female nudity, and the edits were so severe that a new score was needed, with Les Baxter (The Dunwich Horror) replacing Wilfred Josephs (The Deadly Bees). Scream! Factory’s The Vincent Price Collection III, released earlier this year, includes both cuts of the film, along with Price’s Master of the World (1961), Tower of London (1962), Diary of a Madman (1963), and the TV special “An Evening with Edgar Allan Poe” (1970). Cry of the Banshee, a minor film in Price’s filmography, receives the best treatment it’s likely to ever get.

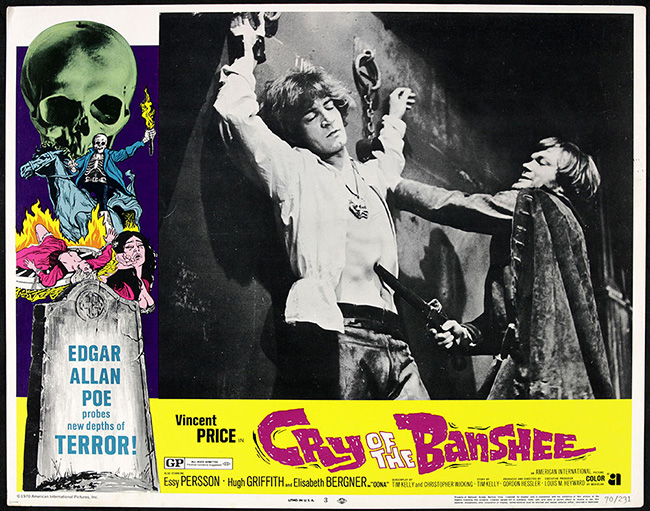

Sean Whitman (Stephan Chase), the Magistrate’s son, interrogates Maggie (Quinn O’Hara), caught with witch’s charms.

Price plays Lord Edward Whitman, the Magistrate of a small English village in the 16th century, who is obsessed with maintaining authority over his subjects. One of his chief means of exercising power is exposing witches in and around his village, drawing a direct parallel between this character and Price’s revelatory performance as Matthew Hopkins in Michael Reeves’ 1968 classic The Witchfinder General (part of the out-of-print The Vincent Price Collection Volume I). This is obviously the lesser film, influenced by Witchfinder but taking the premise in a slightly different direction. In fact, the film might bear more in common with Twins of Evil (1971) or The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) – for here Price’s self-righteous witchhunting finds itself up against a real supernatural force, one that preys upon the young and the “heathen.” As with those films, there is a clear line drawn between the older generation and the younger, forcing a parallel between Merrie Olde England and clashes with the 60’s counterculture. (The ending credits identify members of the Whitman House as “The Establishment.”) The real witches of Cry of the Banshee live out in the woods, enacting druidic rites in white robes and with garlands in their hair. It’s only when Price discovers their coven and brutally slaughters most of their members – his men throw a net over some of the young witches and hack away at them with axes, in one of the film’s most shocking scenes – that the coven leader, Oona (Elisabeth Bergner, The Rise of Catherine the Great), turns to Satan for vengeance. “Kill, kill, kill!” becomes the new chant of the young witches. Meanwhile, Price’s Lord Whitman tries to maintain order not just in his village, but in his own household: his latest wife, Patricia (Essy Persson of Radley Metzger’s Therese and Isabelle), is slowly succumbing to depression and madness as she witnesses her husband’s murderous impulses and is even raped by her own stepson, Sean (Stephan Chase, Macbeth); and his daughter, Maureen (Hilary Dwyer, Witchfinder General), is having an affair with a servant, Roderick (Patrick Mower, The Devil Rides Out), who possesses a supernatural power over animals. A mad dog appears to be on the loose, slaughtering sheep, but the villagers believe the ubiquitous howl to be that of a banshee, who has cursed the family of Whitman. This plot is convoluted.

Lobby card

So convoluted, in fact, that – in watching the director’s cut – when I reached the almost halfway point in the film in which Oona invokes Satan for vengeance against the Whitman family, I wrote down: Oona curses his house (although everyone already though it was cursed, so…shouldn’t this scene have come earlier?). Indeed, in the original theatrical version (included on the disc), the film opens with this scene, but Wicking and Hessler preferred it come later, after we get to know the Whitman clan. In the director’s cut, prominence is placed on Lord Whitman’s Witchfinder General-esque tactics against those he deems witches, so that by the time we reach his massacre of the witches in the woods, we have no room for doubt that the fall of Lord Whitman’s household will be his own doing. But given that the banshee element is introduced at the very start of the film, it is unclear just what purpose the banshee ultimately served; that early on, Oona had not yet cursed the Whitmans. Was the banshee truly just a mad dog, then, and is all that Gothic atmosphere wasted on a red herring? Oona’s agent of vengeance granted by Satan is Roderick, marked by an occult medallion he wears around his neck. In the director’s cut, Roderick’s medallion is introduced too soon; he should be shown with this after Satan brings Roderick forward as the avenger, since there seems to be a direct link between the medallion and his supernatural nature. The fact that his appearance in Oona’s temple in the woods is edited to come right before he’s shown back in bed, tormented by a nightmare, is even more confusing: was the other Roderick just an apparition? Are there two Rodericks? Eventually, Cry of the Banshee will resolve itself into a much more simplistic werewolf story, with Roderick transforming into a hairy wolf-like monster before our eyes (sort of – the makeup is so cheap that Hessler wisely decides to hide it in shadows as much as possible). On the whole, the script suffers from too much rewriting and not enough. It’s crowded with plot elements and characters, and doesn’t wrangle them all coherently.

Vincent Price as Lord Edward Whitman.

This is not to say there aren’t really strong ideas here, the most evocative of which is Price lording over his hall and servants, engaging in all sorts of debaucheries, interrupted occasionally by the unnerving banshee call from outside – an intangible threat that can’t be held at bay forever. This evokes Roger Corman’s masterful The Masque of the Red Death (1964). And the final scene, in which Price realizes that he hasn’t triumphed over his supernatural assassin after all, is effectively chilling. But something’s off about Cry of the Banshee, whether it’s the cluttered narrative (there are enough characters to support a Shakespearean drama, but not all of them are important), the fact that almost all the nudity comes about as a result of some kind of sexual assault (including one with incestuous overtones), or the inconsistent performances (Essy Persson seems to be struggling the most). Nonetheless, the film, in its censored theatrical release, was a hit. Perhaps it was enough to just throw out the words “Poe” and “Price.” One clear advantage that the director’s cut has over the theatrical is to see the original opening credits, which feature cut-out animation from none other than Terry Gilliam, who was still working on Monty Python’s Flying Circus at the time. His credits are eerie, fun, grotesque, and surreal – what Cry of the Banshee might have been, with just a little more time, imagination, and care.