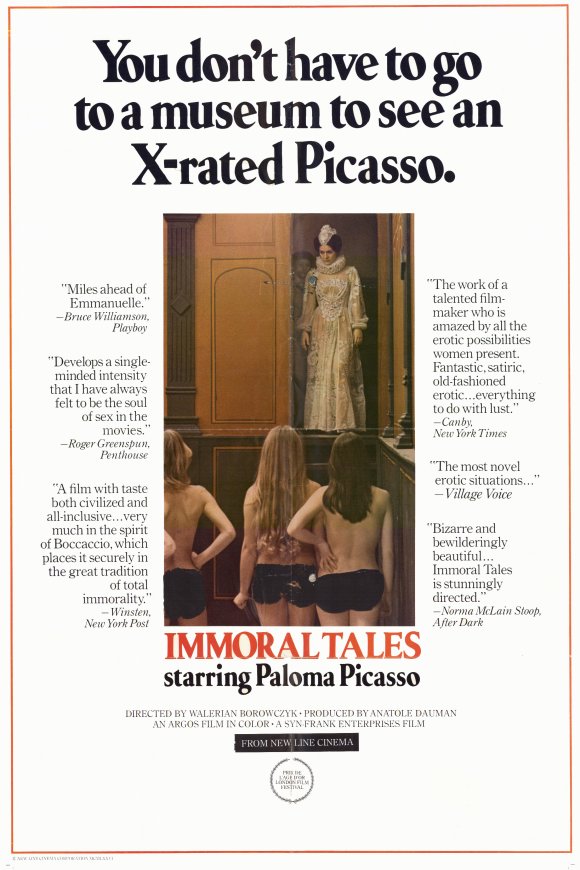

The Polish-born filmmaker and artist Walerian Borowczyk has been undergoing something of a critical reappraisal recently, with some of his films getting the Blu-Ray treatment and an exhaustive retrospective programmed in 2015 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Borowczyk began his career as a painter and poster artist before transitioning into acclaimed, surrealistic animated short films and finally feature films. His growing inclination toward explicit eroticism began to isolate critics in the 70’s, though his Surrealist’s attitude toward shock, blasphemy, and striking juxtapositions remained heatedly front and center, such as in his box office hit Immoral Tales (Contes immoraux, 1974). (In all fairness, explicit sexuality had long been a trademark of the Surrealists, and Borowczyk was somewhat affiliated with the movement.) In the wake of Pasolini’s unexpected success The Decameron (1971), peasant or medieval-themed erotic anthologies became a cottage industry in European cinema, and Immoral Tales, particularly with its title, promised more of the same. Pasolini’s film happens to be a work of art with a strain of innocent eroticism; most of the imitators were merely softcore (or hardcore) porn. Although it isn’t hardcore (it’s close), Immoral Tales pushed the boundary between art film and overt voyeurism. Of course, by 1974 porn was near its zenith in cinemas – Deep Throat had been released just two years earlier. Wider swaths of the public were prepared to gaze at sexual acts on the big screen, either as couples, or as individuals lurking in the back rows. Immoral Tales benefited from the implication that it was the work of an artist, and was therefore erotic art; this French film was produced by Anatole Dauman and his company Argos Films, also responsible for such prestige La Nouvelle Vague pictures as Last Year at Marienbad (1961) and Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), among many others. But in fact, Borowczyk was not pursuing anything complex. Certainly in each of the four segments, story is not a concern. The “tales” don’t feature conventional beginnings, middles, or ends. There are, however, a few climaxes.

A tale told by a face: In “The Tide,” Walerian Borowczyk lingers on the lips of Lise Danvers. In the final image (bottom right), she is not just ravished but wet from the high tide.

Immoral Tales consists of four short films which regress backward in time, from the twentieth century to the fifteenth. The topics range from blowjobs to blasphemy to murder and incest. A fifth segment, “The Beast of Gévaudan,” added bestiality to the mix, and was included in an early cut of the film before being removed by Borowczyk. This wasn’t a retreat but a doubling-down: the short was expanded into the feature length The Beast (La Bête, 1975), becoming his most notorious feature film. But there’s plenty to outrage sensitive viewers in Immoral Tales. Or Catholics – Borowczyk shares with Luis Buñuel a delight in exposing corruption, lust, and hypocrisy in the Church (you might know what’s coming when the final segment is called “Lucrezia Borgia”). He opens with a statement of purpose, a quote from La Rochefoucauld’s 17th century Maxims: “Love, as pleasant as it is, is liked even more for the ways in which it shows itself than for itself.” Therefore the film sets itself up for a demonstration of the varieties of love – or, rather, lovemaking; it’s a thesis that isn’t quite fulfilled, but at least presents a suggestion of logic to this erotic collection. What’s more convincing is the film as a collection of Borowczyk’s own fascinations and fixations. “La Marée” or “The Tide,” the first tale, is based on the first story in the 1971 collection Mascarets by André Pieyre De Mandiargues, who also wrote La Marge, adapted into a film by Borowczyk in 1976. Julie (Lise Danvers, Bloody Murder) bikes with her older cousin André (Fabrice Luchini, Claire’s Knee) to a stony beach of tidepools and cliffs, timing the arrival of high tide and commanding her to perform oral sex as the waves rush in. (The plot reminded me of the short stories of De Sade.) Despite the discomfort of the one-sided, submissive relationship between these two cousins, the director is fully engaged, and therefore it is one of the most vividly sensual and complete tales in a scattershot anthology. Undoubtedly Borowczyk’s fixed gaze on Julie is voyeuristic, but every element in this piece is of a piece: seaweed clinging to a shoulder, scraped legs on rocks, birds floating over crashing waves and under a gray sky, the red mark on newsprint noting the time of high tide, and fetishistic close-ups of Julie’s lips. It never adds up to much more than the concluding sentence, “Now you’ll know what the tide is,” but at least it sets expectations for the rest of the film. This is a film about sex, less so the characters engaging in sex.

In “Thérèse the Philosopher,” a discovery of forbidden images.

“Thérèse the Philosopher” opens with a news clipping: “10 July 1890: The locals demand Thérèse H. be declared a saint, the devout young girl raped by a vagrant.” The rape happens at the end of the segment, as an afterthought (in the distance, and quickly cutting away – it’s only important that we know it’s about to happen). Instead, the gauzy focus is on how the sexual obsessions of Thérèse (Charlotte Alexandra, A Real Young Girl) are fueled by her spirituality. She is first seen wandering through an empty church stroking every phallic shape (a pipe organ is apparently a bounty) while talking to a real or imagined Jesus Christ, who wishes her to partake of his body in a very different way than Communion. She’s chastised by an older guardian who locks her in her room, but here she finds all the stimulation she needs in religious vestments, an ugly wooden doll, a portrait of a mustachioed gentleman, and a book called “Thérèse the Philosopher” which consists of pornographic illustrations. Let’s cut to the chase: the majority of time here is spent with Thérèse masturbating with cucumbers, and provides the closest Borowczyk gets to actual pornography. There’s a touch of wit to the image of said mustachioed gentleman splattered with cucumber seeds, but the greater impression is that in 1890 one would use whatever sexual aids one could find.

Countess Báthory (Paloma Picasso) takes her famous bath.

Much better (though even more interminable) is the tale of Countess Erzsébet Báthory, who abducts young women in 17th century Hungary and bathes in their blood. This, the best known (and factual) story, has been adapted many times, notably as the Hammer film Countess Dracula (1971), with Ingrid Pitt as the Countess. What I enjoy most about Borowczyk’s take is that he knows that you know what’s going to happen, and so delays the famous blood-bath, instead focusing upon the luxurious imprisonment of the young women and the wordless communication between Báthory (Paloma Picasso, daughter of Pablo Picasso) and her female page, Istvan (Pascale Christophe, Immoral Women). A long group shower scene is here largely for exploitation purposes, but when the naked young women gather in a red and black chamber, pursuing the Countess in circles about the room in hopes of touching her white dress and pearls, the tableau is truly striking. Finally they tear her dress to shreds, and fight over the pearls – one girl is glimpsed hiding pearls in her vagina. The madness that ensues skips over explicit violence, settling for an impressionistic montage of images (Báthory slipping into a frothing red bath; Istvan wiping blood from her saber) that reminds of Nicolas Roeg. The theme of exploiting the lower classes couldn’t be more clear, but it’s also the most wildly satirical, making this the best segment in the film, even if it’s hampered by endless close-ups of asses and pubic hair. My wife calls Immoral Tales‘ eroticism “clinical,” which is the best way to describe the film’s reliance upon segmented shots of female bodies, as though the camera is engaged in anatomical dissection. Even with the satire on display here and in the final segment, it’s clear that the film is more interested in surface than subtext.

Pope Alexander VI (Jacopo Berinizi) seduces Lucrezia Borgia (Florence Bellamy).

And this is a film that’s more interesting to write about than to watch. The “Lucrezia Borgia” short, which closes the film, has little more to it than its premise, realizing the rumors of incest within the household of Pope Alexander VI (Jacopo Berinizi), as the Pope has a three-way with his daughter Lucrezia (Florence Bellamy, The Key is in the Door) and son, Cardinal Cesare Borgia (Lorenzo Berinizi). Gross? Sure. But this is actually the least explicit of the segments, as Borowczyk is more interested in visual dissection here, too, with the preference being on the sacred objects and clothing which are removed or violated in various tiny blasphemies. Anyway, he frequently cuts away to a ranting Dominican priest, Hieronymus Savonarola (Philippe Desboeuf), who assures us that all this is very wrong. (The Báthory piece also indulges in some moralizing, but of a more disappointing variety: after Istvan has a lesbian tryst with her Countess, she turns her into the authorities, and savors a heterosexual kiss with her co-conspirator.) The final image of Immoral Tales is a happy newborn – the result of incest, yes, but innocent and joyful, this spawn of sin. Perhaps it’s difficult to be shocking and heretical after Buñuel’s Viridiana (1961) or Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971). By the mid-70’s, very little was forbidden on the screen, which means that both Immoral Tales‘ smirking shots at the Church and its peepshow sensibilities have a diminished value. Nonetheless, there are some potent images to be found, filmed like illustrations in a Victorian dirty book.