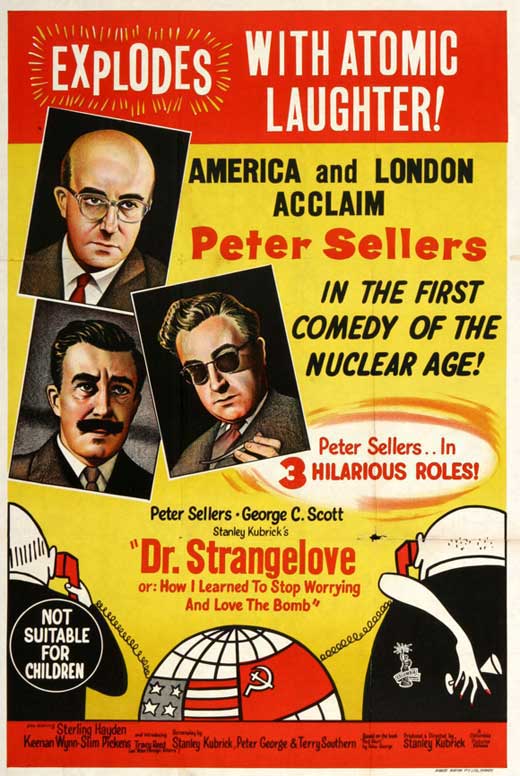

Famously, Stanley Kubrick purchased the rights to the straight-faced Cold War thriller Red Alert by Peter George, but decided the material was too dark to be treated seriously, and rapidly began to transform it into a satire with George assisting with the screenplay and The Magic Christian author Terry Southern brought in to sharpen the edges. The result, by general consensus, is a masterpiece, but in watching the film for the umpteenth time (now on the new Criterion Blu-Ray), I began to wonder how many other comedies function just as well as sweat-inducing thrillers. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) is claustrophobic and uncomfortably intense, even though you’re laughing through much of it. Perhaps this was the birth of discomfort comedy; Kubrick doesn’t want us to ever be comfortable, because the world is about to be destroyed. He always keeps us aware of the ticking clock as the Strategic Air Command 843rd Bomb Wing closes in on the Soviet Union, following orders from the deranged Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden, The Killing), who thinks that Commies are stealing “our precious bodily fluids.” The three-letter recall command, the only possible way of cancelling the order, is known only to Ripper. Locked in a room with Ripper is the only man with the means of extracting the code or bringing the general to his senses, Group Captain Mandrake of the RAF, the executive officer under Ripper (played by Peter Sellers, of Kubrick’s Lolita, and who had starred in The Pink Panther the previous year). In Washington, President Merkin Muffley (Sellers, once more) is debriefed by General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott, at his very best) in the War Room, and before his gathered staff he tries to find a fast solution in a situation with no solutions. From the continuity script:

Turgidson: Plan R is an emergency war plan in which a lower echelon commander may order nuclear retaliation after a sneak attack if the normal chain of command is disrupted. You approved it, sir. You must remember. Surely you must recall, sir, when Senator Buford made that big hassle about our deterrent lacking credibility. The idea was for Plan R to be a sort of retaliatory safeguard.

Muffley: A safeguard.

Turgidson: I admit the human element seems to have failed us here.

He only has eighteen minutes before the bomber planes enter Russian radar. Tick, tick, tick… So he brings in the Russian ambassador, Alexi de Sadeski (Peter Bull, Tom Jones, The Old Dark House), and together they have a conference call with Soviet premier Dimitri Kissov.

Muffley: Hello? Hello, Dimitri? Listen, I can’t hear too well, do you suppose you could turn the music down just a little? Oh, that’s much better. Yes. Fine, I can hear you now, Dimitri. Clear and plain and coming through fine. I’m coming through fine too, eh? Good, then. Well then as you say we’re both coming through fine. Good. Well it’s good that you’re fine and I’m fine. I agree with you. It’s great to be fine.

The clock keeps ticking…

General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott) lectures in the War Room.

As with all great satires, it’s important that the film adhere as closely as possible to the standards of that which it’s satirizing. A satire of horror films should look and behave much like a horror film. And Dr. Strangelove looks and behaves like a Cold War thriller – like an adaptation of Red Alert. The influence of the source material is strong, despite the shift toward comedy. The verisimilitude is important, and both George’s background (he was a flight lieutenant and navigator in the RAF) and Kubrick’s notoriously extensive research inform the film. There is more that’s factual in the film than one might expect in watching it, from Plan R’s paranoid and inherently irresponsible fail-safes to the last-minute “mine shaft” fallout shelter discussions; it was Kubrick’s genius to recognize that the truth was the stuff of black comedy. Yet by retaining the framework of George’s thriller, it still functions as a thriller. I’m coming to realize that each time I watch Dr. Strangelove, I have the strange feeling that I’m running out of air. Kubrick throws us in a sack and tightens the drawstring. Many of the funniest gags come from moments when the hopelessness of a situation becomes clear and we move another space across the gameboard to doomsday. Take the scene in which Mandrake tries to smooth-talk the secret code out of Ripper. “Now supposing I play a little guessing game with you, Jack, boy,” he says, while Ripper takes a gun into the bathroom and closes the door behind him. “I’ll try and guess what the code is,” Mandrake says, and he’s interrupted by the sound of a gunshot from behind the door.

Sterling Hayden as Brig. Gen. Jack D. Ripper.

Nothing in the cinematography indicates that it’s a comedy. The black-and-white is stark, the compositions monolithic, from Ken Adams’ celebrated War Room, where the “big board” leans imposingly over the President’s staff, to the Mount Rushmore close-ups of Sterling Hayden and his phallic cigar, nearly selling the importance of drinking “grain alcohol and rain water.” The scenes of combat outside Ripper’s base are shot with handheld cameras, and look like real combat footage. It’s just that we know the two sides engaged in conflict are both the same side, each following their commands and unloading friendly fire. We upload the context; Kubrick’s camera just sees a war documentary. In the B-52 with Major King Kong (Slim Pickens, Blazing Saddles) and his crew (including a young James Earl Jones), proceedings are somber as they fly toward their bombing target, across the Arctic and into Russian territory. When Mandrake, against all odds, discovers the three-letter recall command, it should be a moment of jubilation, of cathartic release – except that we know that Maj. Kong’s bomber is still on course, his radio damaged, unable to receive the order to turn back. The hatch won’t open, and Kong has to climb onto the bomb and repair the circuit. The comedy, the real cathartic release, is the opening of the bay doors, and Maj. Kong screaming “Yeehaw,” waving his cowboy hat as he rides the bomb to oblivion. Comedy and horror and absurdity are fused together. With the End having arrived, it’s only left for ex-Nazi Dr. Strangelove (Sellers) to put on the film’s only broad and (Clouseau-style) slapstick performance, a relief for the audience in the face of the coming annihilation. The plan he lays out excites the men, not just for the possibility of their survival, but for the male sexual fantasy it invokes. It’s only a fantasy, and that’s all that’s left to them. As we watch footage of nuclear explosions and “We’ll Meet Again” plays, the reassurance is purely ironic. Don’t worry. The world’s ending. Stop worrying and love the bomb.