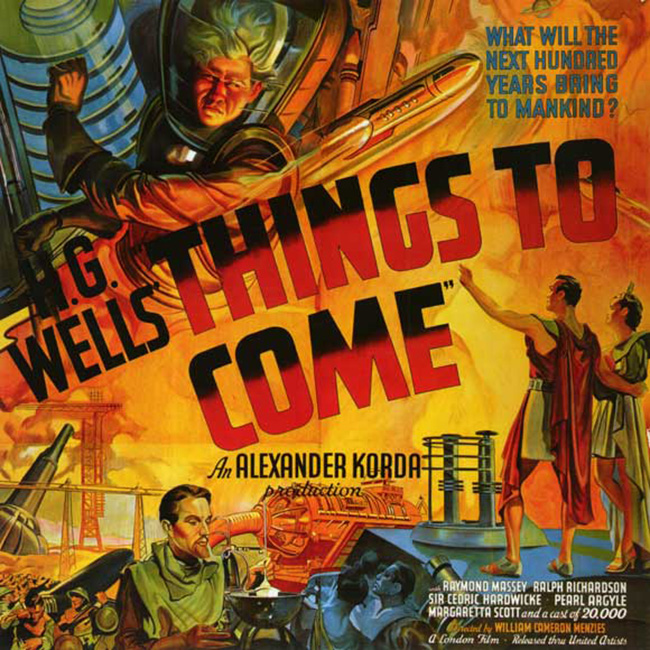

By the 1930’s, H.G. Wells had become one of the most prominent political and sociological thinkers and futurists of his time, writing volume after volume speculating on where mankind was headed and where it ought to go, with technology and reason playing prominent roles. It wasn’t enough to write about the future. He was now taking ownership of it, offering what he hoped would be practical road maps toward a utopian tomorrow. Therefore when he initiated his major foray into feature films, Things to Come (1936), he was interested in a much more cerebral science fiction fable than the works that had brought him fame in the late 19th century: The Time Machine, War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man. The story was based on his 1933 The Shape of Things to Come, a history book looking back from a century in the future; but it was also informed by his eat-your-vegetables nonfiction study The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1933). Eager to have the Wells name on a project, noted film director and producer Alexander Korda offered the author a contract to write a screenplay for Korda’s London Films. Wells made sure the contract stated that his screenplay could not be altered – though the film was ultimately shortened – and the result is an unusually didactic and inert science fiction film, in which the characters are not human beings but symbolic props. Distinguishing the film is its extraordinary design. Korda hired William Cameron Menzies, who had directed a number of films including the striking pulp Chandu the Magician (1932), but who was best known as the ingenious art director for films like The Thief of Bagdad (1924). Menzies had an eye for scale and arresting images, which made him ideal for filming the fantastic. The set designer was Alexander’s talented brother Vincent Korda (The Private Life of Henry VIII, The Third Man). Filling out this murderer’s row were cinematographer Georges Périnal (The Blood of a Poet, Le Million, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp) and Bauhaus painter László Moholy-Nagy. Wells insisted that his son, Frank Wells, contribute to the art direction, though even with the stunning images that the film contained, the author was never satisfied with the look of Things to Come. He was a difficult man to please: the film looks fantastic.

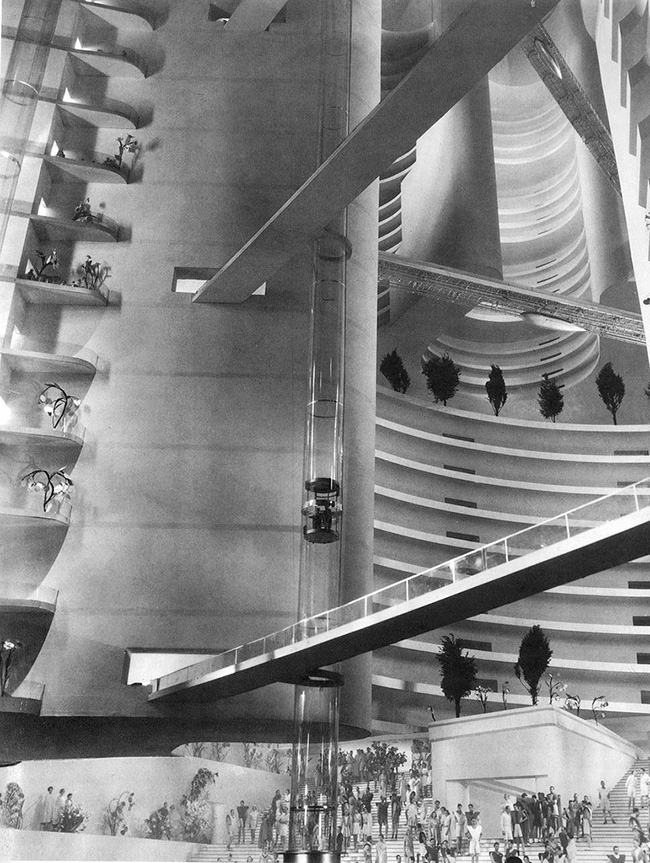

Looking back on the architecture of 1936 from the perspective of 2036.

Despite its dry-as-toast script (originally called Whither Mankind?), Things to Come is a milestone in science fiction cinema, perhaps by default. In those days of pulp SF magazines and SF movie serials best suited for children, serious SF was scarce. Fritz Lang’s landmark Metropolis (1927) was an exception to the rule, but Wells was not a fan. In a lengthy review for the New York Times, Wells called the film “silly” and focused upon its lack of originality (cribbing ideas from Mary Shelley and Karel Čapek, he notes), but mostly he disliked its unrealistic depiction of a futuristic society. “One is asked to believe that these machines are engaged quite furiously in the mass production of nothing that is ever used, and that Masterman grows richer and richer in the process,” he wrote. “This is the essential nonsense of it all. Unless the mass of the population has the spending power there is no possibility of wealth in a mechanical civilization.” He was also not persuaded by Lang’s vision of a vertically oriented and stratified urban society. “That vertical city of the future we know now is, to put it mildly, highly improbable. Even in New York and Chicago, where the pressure on the central sites is exceptionally great, it is only the central office and entertainment region that soars and excavates. And the same centripetal pressure that leads to the utmost exploitation of site values at the centre leads also to the driving out of industrialism and labour from the population center to cheaper areas, and of residential life to more open and airy surroundings…The British census returns of 1901 proved clearly that city populations were becoming centrifugal, and that every increase in horizontal traffic facilities produced a further distribution. This vertical social stratification is stale old stuff. So far from being ‘a hundred years hence,’ Metropolis, in its forms and shapes, is already, as a possibility, a third of a century out of date.” His Things to Come was going to serve as a corrective. His 100-years-hence city would not touch the sky, but be driven underground.

Wells’ underground Everytown of 2036.

That Wells was so disinterested in the drama or characters of Metropolis is telling as to the approach he would take with his film. As a futurist, he wanted the vision of the future to be as accurate as possible (from his view, anyway); he found lazy touches (“the motor cars are from 1926 or earlier”) too distracting to engage with the metaphor-driven allegory Lang presented. In this way, his commentary was a bit like Neil DeGrasse Tyson tweeting the scientific inaccuracies of movies like Gravity. Yet Wells was interested in political and sociological allegory. Novels like The Time Machine and In the Days of the Comet accomplished this quite well. Things to Come, however, reduces its characters to delivering topic sentences and concluding paragraphs. There is very little in the way of drama or action. The story is rigidly divided into three acts, all set in “Everytown,” England: Christmas 1940, a devastated post-war 1970, and a Utopia of 2036. Though all three have their compelling elements, it is only the second act which offers up some semblance of human drama, allowing the film to briefly flutter to life. World war – Wells’ eerie prediction of WWII – has raged for decades, and by 1967, half the human race has been exterminated by chemical warfare called “The Wandering Sickness.” The stricken are called “Wanderers,” and they’re shot down before they can infect anyone else – a brief and effective passage in the film anticipating George A. Romero. Three years later, in the ruins of oil-starved Everytown, a despot has come to rule (Ralph Richardson, who offers the only true performance in this film). His is one of many isolated city-states that have resorted to a primitive existence. Both Richardson and his mate, the frustrated-feminist Margaretta Scott, are bemused by the arrival of a man in a flying machine, John Cabal (Raymond Massey, The Old Dark House). Richardson thought the technology of flight to be lost, but now he dreams of building his own fleet of fighting aircraft, and raids the nearby “Hill People” to gain access to their coal and begin to manufacture fuel once again. Cabal, who has come from a technologically advanced society, “Wings Over the World,” based in Basra, Iraq (!), is imprisoned. Richardson’s only engineer, Richard Gordon (Derrick De Marney), looks up to Cabal and plots a revolt. This divide between the science-based society and the war-obsessed brutes is the same kind of allegorical structuring that Wells was using way back when he was writing about the Eloi and the Morlocks, although they were slightly different signifiers. But whatever brief drama unfolds in Act Two, it is dissipated as quickly as the “peace bombs” that Wings Over the World drop on the city, a sleep gas that pacifies, allowing a brighter future to commence. The conflict that develops in Act Three is unconvincingly developed, though one can at least sit back and enjoy the fabulous matte paintings and sets decorated with glass furniture. In 2036, the descendant of Cabal (Massey again) attempts to send bright young people to the Moon by firing them out of his Space Gun (a giant cannon). A mob of Luddites rise up against him, stirred up by Theotocopulos (Cedric Hardwicke, Suspicion), who distrusts the role science is playing in society.

The bombed-out Everytown of 1970.

Ultimately, Wells hoped to present an optimistic view of the future, to show that after enduring many trials, we could finally eradicate warfare and the petty concerns of modern politics, embracing mankind’s destiny of exploring the stars with science and reason as our tools. Some of his predictions were accurate: though his vision of the next World War was heavily informed by his experience with the First (gas attacks, biplanes), the scale and devastation of WWII – which would begin earlier than he guessed – would set the course for the rest of the twentieth century, albeit in different ways. Even the third act’s depiction of the hostility between men of science and “Luddites” is reflected in modern debates about global warming and the resentment toward scientists and universities from extreme Conservatives. He was correct that cities would continue to grow outward rather than upward, Dubai excepted; it remains to be seen if we will begin burrowing underground. We did get to the Moon, but much sooner than Wells guessed, and not via a cannon-sent projectile. Whatever its scientific accuracies, Things to Come works best not as an essay but as a visual experience. The high point is a montage depicting the advancement of technology into the twenty-first century, spinning whirling flashing bubbling sciencey things that do God knows what, leading to images of Everytown transformed and idealized. (And, because it is the future, everyone must wear togas with large shoulder pads.) But even in the first two acts, Menzies delivers one arresting sight after another, from the spectacular bombing of Everytown to its post-apocalyptic aftermath. In one haunting montage, a boy playing at being a drumming soldier is suddenly dwarfed by the silhouettes of men marching to war. Later, we see him dead beneath rubble. Another soldier is crucified on a wire fence. Though Menzies and Korda weren’t allowed to change a word of Wells’ script, it is in striking images like these that Things to Come truly finds its resonance.