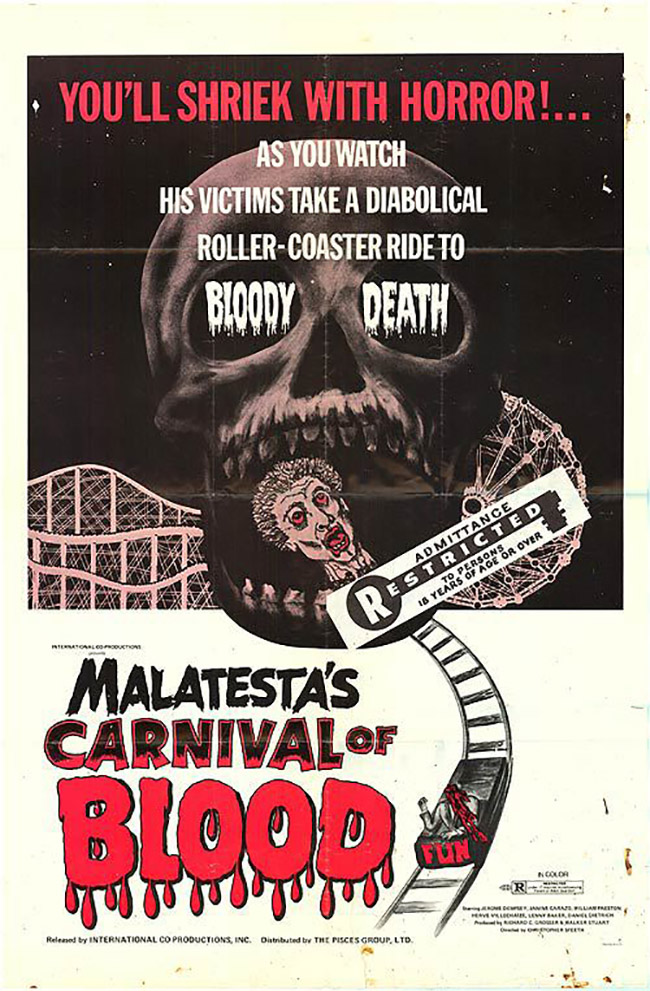

Filmed after hours in a Pennsylvania amusement park called Six Gun Territory (now abandoned), Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood (1973) was, for decades, completely forgotten, but thanks to champions such as Nightmare USA author Stephen Thrower, this surreal gem of regional horror has belatedly adopted a cult following, culminating in a Blu-Ray release as part of the Arrow box set American Horror Project Volume 1. It is the only feature film from director Christopher Speeth, who had previously directed experimental shorts, and as it was, he was barely able to complete the film. With much of the budget spent on film stock, there was little left to spend on-screen, and they could rarely afford more than one take. Nonetheless, with full access granted to Six Gun Territory after the gates had closed, Speeth benefited from a surprisingly grand set design. Who hasn’t wanted free reign to an amusement park without crowds and lines, or looming security guards? Speeth orchestrates gory murders amidst the attractions, and even stages a duel with a villain on an active rollercoaster. But even this doesn’t quite describe the unique vibe of Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood. As the mad film goes on, it becomes both deliberately and accidentally disorienting and dream-like. The plot and characters are sometimes hilariously incoherent, particularly in the early going – a result, it seems, of several scenes from screenwriter Werner Liepolt’s script never getting filmed, the budget already strained to breaking. But by the final act, it’s hard not to fall under the film’s boozy spell. One thing at which Speeth brilliantly succeeds is capturing the dizzying feel of making circles in a funhouse with no exit in sight.

The premise is inspired. In the limestone caverns beneath a carnival, cannibalistic ghouls devour park visitors. (We never actually see the park packed with guests. There is only ever one or two people wandering through at a time.) At first the proprietor appears to be Mr. Blood (Jerome Dempsey, Network), who looks and sounds a bit like Orson Welles, and wanders around in a Dracula cape delivering odd monologues. But we gradually learn that the real overseer is his master Malatesta, who bears a resemblance to Frank Zappa (or, if you will, the Master from Manos: The Hands of Fate), and spends most of his time underground surrounded by his ghouls, who like to consume their victims while Lon Chaney’s The Phantom of the Opera and The Hunchback of Notre Dame are projected behind them. The heroine is Vena (Janine Carazo), who takes a job at the park, befriending her co-worker Kit (Chris Thomas, who looks a bit like Parker Stevenson), and together they begin to suspect the nature of their employers. One clue: the mute, gray-skinned custodian with a glass eye (William Preston, The Fisher King) keeps trying to stab them with the point of his trash picker. Other characters include Vina’s grating parents (Paul Hostetler and Betsy Henn), who spend most of the film in their RV yelling at each other and becoming paranoid about the carnival, to the point of Mr. Norris drawing a gun and firing it out the window. As the film progresses and more park visitors are killed – one by decapitation on the roller coaster – Vena and Kit find they can’t escape, the fence electrified. And when Kit’s impaled body turns up in the carriage of a ferris wheel, Vena seems to fall, Alice-like, into a world where there is no distinction between dream and reality. She spends much of the film in her nightgown, tumbling through the world beneath the carnival and encountering surreal sights that look like the bad acid aftermath of a 60’s hippie Happening – an upside down Volkswagen swinging from a ceiling and insulated with red cellophane, creepy papier-mâché dolls and dummies, even a giant whack-a-mole with ghouls popping their heads up from inside.

Vena (Janine Carazo) and Mr. Blood (Jerome Dempsey) beneath the carnival.

Other servants of Malatesta include Mr. Bean (Tom Markus), who has a hook for a hand and is not Rowan Atkinson; the fortune teller Sonja (a cross-dressing Lenny Baker, Next Stop, Greenwich Village); and the rhyme-chanting dwarf Bobo, played by Hervé Villechaize one year before he pranced through a different deadly funhouse in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). His best scene comes toward the end of the film, when he goads a visiting police officer into trying his hand at the dunking booth, unwittingly drowning the bound-and-gagged victim inside. The deeper we explore the underbelly of Malatesta’s carnival, more is revealed, including the jealousy of Mr. Blood toward his master, which leads Blood to kidnapping Vena and drawing her blood by a syringe so he can drink it (Mr. Blood happens to be a vampire). Occasionally traces of intentional surreal comedy emerge, such as the sight of Blood standing before the Norrises’ burned-down RV with a fire extinguisher which he’s barely bothering to use. It’s one moment that works almost in spite of itself, and these moments accumulate toward the end of the film, overpowering the rampant amateurishness of different aspects of the production, including bad line readings and awkward camera angles. We can sense the community effort that went into the production – a host of locals recruited to play the teeming ghouls, “underground” sets that are decorated to the hilt like the ultimate Halloween party – and the only rational impulse is to root for the film. And the film rewards you. There are shots in this film which are unexpectedly remarkable, the result of on-set ingenuity, like Vina lying unconscious at the bottom of the frame while the projected image of Mr. Blood rises up in the background on a screen, leering at her. Or Villechaize in a giant, empty chamber draped with white sheets, propped up on a black throne granting him an unexpected height, a scene that Alejandro Jodorowsky might admire. Or Vina crawling through a vaginal hole draped with that ubiquitous red cellophane; or Malatesta at last emerging in the daylight to enjoy one of the rides, flying, legs dangling free, smiling – a ghoul in the carriage behind him. I have watched this film twice: once at 5:30 in the morning, when its wobbly, weird style lined up perfectly with my just-waking headspace; and once in the early evening when I was fully awake – yet, by the end, I was feeling just as topsy-turvy. In other words, the film works no matter how you watch it: it draws you into its funhouse, surrounded by wild-eyed carnies and madrigal-singing cannibals.