The creaking of a rocking chair. A tune hummed very softly. Corpses strewn about an attic. The girl in the chair, with the defaced plastic doll in her arm, has long ago been smothered by a plastic bag, and she looks like an insect trapped in amber. A voice whispers in a broken cadence: “Agnes? It’s me, Billy.” You never see the speaker, not fully. He’s usually just a hand or a pair of legs, sometimes a fist clutching an improvised weapon before the camera – whatever can be used for killing in this mostly empty sorority house one December in the early 70’s. Most often he’s just a shadow in the background, while the sorority sisters are looking in the opposite direction. On paper, Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974) shouldn’t work as well as it does, and it can easily be lost amidst the stacks and stacks of slasher films that followed. Unseen killer – shots often taken from his point of view? A body count of sorority girls, picked off one by one? A fake-out ending? The calls are coming from inside the–? Check, check, check. But it is not only one of the first films to do all those things, it also handles them extraordinarily well, without condescension, and with quotable dialogue and believable characters. Yes, many of the moments in the film would soon become clichés, but one of the reasons Black Christmas is so enduring is that, here in prototype, they are not treated like clichés. Bob Clark believes in them, and he persuades you of the reality of the peril. The first time I watched Black Christmas I was jarred. I was halfway through the film before I realized that the movie I thought I was watching was vastly inferior to the movie that I was actually watching, and I only realized this because my body was beginning to ache from nervous tension; I was in a cooking pot, and Bob Clark had turned the water up to boiling so gradually that I didn’t notice until it was too late.

John Saxon as Lieutenant Ken Fuller.

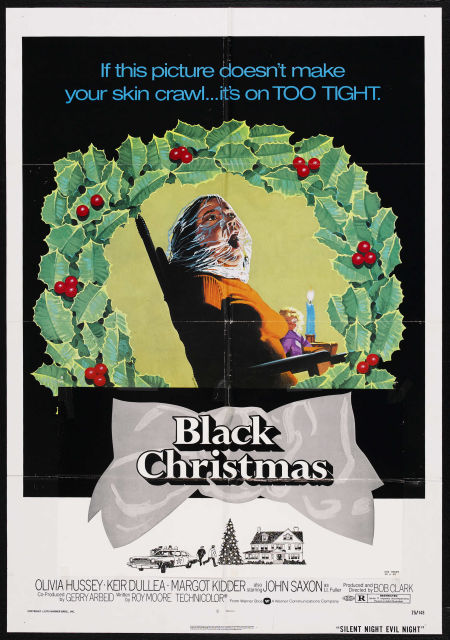

Wait, Bob Clark – that Bob Clark? The one who directed A Christmas Story just nine years later? Yes, and the one who made Porky’s (1981) right before that. Clark was a chameleon, shying from the auteur label. Like a studio director of old Hollywood, Clark adapted his style to best suit the material. But he wasn’t from Hollywood; he was a Canuck, and Black Christmas was one of a large number of “Canuxploitation” films with an eye toward becoming a hit at American drive-ins. It wasn’t his first horror film, either. He had previously made Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972) and Deathdream (1974), and by now he had a sure hand at balancing strong performances and ratcheting tension. One of the most striking things about Black Christmas is how well directed it is, the camera movement acting as a storyteller just as in a Hitchcock film. Notably, the opening sequence is shot from the killer’s POV, stalking outside the windows and climbing a trellis to invade the sorority house of Pi Kappa Sigma. But on this viewing I noticed a different scene where Clark breaks from the main characters to observe them through a window, their dialogue muted; it’s a moment that’s not necessarily the observation of the killer, but instead a reminder of the threat which hovers over them, to keep you on edge. (It also, efficiently, removes extraneous dialogue. We know what they’re saying, so we don’t even need to hear them say it.) More frequently, we see the potential victims while the killer is standing above them on the upper landing, sometimes perfectly exposed if they would only turn around; the ideal device to get the audience screaming advice at the movie screen. This technique was fairly new. Psycho and Peeping Tom pioneered the voyeuristic aspect of horror in 1960, and when the shower curtain is opened on Marion Crane, she’s screaming straight at us, her killer. Mario Bava’s seminal slasher A Bay of Blood (1971) and other giallos, including Dario Argento’s, further developed voyeuristic, POV murders, both sadistic and fetishistic. Black Christmas takes key elements of those films and makes a formula of them which feels like a revelation. It was largely overlooked on its release in 1974, but it had a big fan in John Carpenter. As Clark told it, it was Clark who suggested to Carpenter the premise of a teen slasher film set on Halloween, to be called “Halloween,” an off-hand idea for a Black Christmas sequel which Clark had no intention of actually making. Carpenter ran with it, and even borrowed the idea of opening the film from the killer’s POV, though Carpenter’s take is much more ambitious, prolonged, and attention-grabbing. Ultimately, Halloween (1978) is its own film, but would it have ever happened if it weren’t for Clark’s earlier, Christmas-set slasher? Clark’s film came and went, but Halloween made an impact crater – and sent ripples through the horror genre for a decade.

Jess (Olivia Hussey) waits for the killer’s phone call.

But here’s what Black Christmas doesn’t share with all the slasher films to come. Though it takes place in a sorority house, surprisingly there’s no T&A – neither a gratuitous shower scene nor a lingerie slumber party. The future director of Porky’s isn’t interested, because it would contribute nothing to the story or the suspense. All the girls stay fully clothed, often in layers (it is winter, after all). This feels not like a male fantasy but a real sorority house, from the girls’ somewhat forced pretense of adulthood – best embodied by Margot Kidder’s character, who is always drinking or smoking or talking about sex – right down to the R-rated posters on the walls, which cause deep embarrassment to the father of one of the missing girls when he comes knocking. There’s also very little blood and gore, certainly nothing of the Friday the 13th variety. Only two scenes featuring blood come to mind, one of which – a stabbing with a glass unicorn – is a showstopper more notable for its cross-cutting and the use of a Christmas carol than the explicitness of the killing (it isn’t explicit at all). So why do slasher aficionados hold Black Christmas in such high regard? Because everything Clark has assembled works in harmony toward one purpose: shaking the audience up good. Most of this is achieved using a simple telephone. “Billy,” the stalker and killer, has a habit of phoning up the sorority girls. In the opening minutes we watch as his call interrupts a holiday party, and the young women gather to listen to the latest diatribe from “The Moaner.” The sorority sisters are played by Olivia Hussey (Romeo and Juliet), Kidder (who had recently starred in Brian De Palma’s Sisters), Andrea Martin (pre-SCTV), and Lynne Griffin (Curtains). The call is disturbing for a number of reasons. Billy’s explicit come-ons feel like a violation in context of the hushed “Hark! the Herald Angels Sing” playing in the background and the expressions of shock and fascination from the girls. And his voice keeps changing shape, like a broadcast of a gibberish radio play from the abyss. When Clare (Griffin) questions whether it could just be one person, Kidder’s priceless response is, “No, Clare, that’s the Mormon Tabernacle Choir doing their annual obscene phone call.” To pull off the disturbing calls, Clark used Nick Mancuso for the voice of Billy, but also about five other actors. It’s Norman Bates arguing with “Mother,” squared. In later scenes, each of Billy’s phone calls is accompanied by jarring sounds from Clark’s go-to composer, Carl Zittrer. It pushes you to the edge of your seat.

Mrs. Mac (Marian Waldman) plays reluctant host to Mr. Harrison (James Edmond) when he comes looking for his missing daughter.

As Billy begins offing the sorority sisters, we follow Jess (Hussey) and her deteriorating relationship with possessive boyfriend Peter (Keir Dullea, 2001: A Space Odyssey). (Another tradition is established here: the bodies of the victims remain hidden, all building up to a big “reveal” to jolt the Final Girl.) Jess discovers she’s pregnant, and she wants to have an abortion; Peter wants to keep the baby. Peter, a pianist in the conservatory, begins behaving erratically and violently. This leads to the film’s big question: is Peter really Billy? Some of Billy’s remarks on the phone drop hints that they’re one and the same, and it’s not like there are a lot of candidates, if we have to pick from the cast: the other one, perhaps, would be Clare’s boyfriend Chris (Art Hindle, Invasion of the Body Snatchers). But Clark keeps the film’s story as simple as possible, so that it plays like a dark fable for the holidays. There’s an admirable purity at work. The film’s second half is focused on the attempts by Lieutenant Fuller (John Saxon, A Nightmare on Elm Street) to trace one of Billy’s phone calls. Jess sits by the phone, waiting for it to ring. Fuller sits at his desk in the police station, where his phone has been set to ring simultaneously with the phone in the sorority house. A telephone technician is at the ready to trace the call, which is a physical workout – he needs to actually run down corridors of phone switches to finally arrive at the conclusion that we all know is coming. Finally, there’s the twist ending, which really shouldn’t work as well as it does, but it works gangbusters. Perhaps that’s because it doesn’t answer all your questions. You expect a neat resolution – even the giallos solved their twisted mysteries – and you don’t get one. Those calls, so strange and inexplicable (who’s Agnes, anyway?), never receive a clinical explanation from Psycho‘s psychiatrist. This is how you do it. The latest home video release of Black Christmas is another of Scream! Factory’s grand gestures at the ultimate edition: the first disc features a new restoration based on a 2K scan of the negative, and a second disc houses far more special features than the back of the box suggests. This is the equivalent of a course syllabus on the late Clark’s horror classic. Required viewing for horror fans.