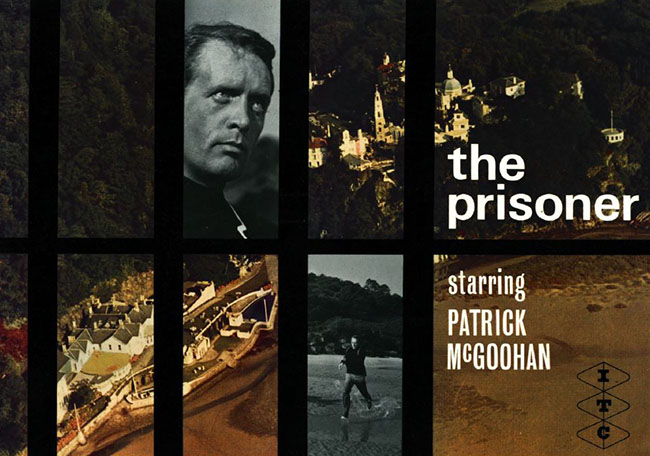

CHECKMATE First UK Broadcast: November 24, 1967 [episode #9 in transmission order] | Written by Gerald Kelsey | Directed by Don Chaffey

SYNOPSIS

When Rover’s approach once more causes the Villagers to freeze in place (as first seen in “Arrival”), No.6 notices that he is not the only one still moving: an old man with a cane, No.14 (George Coulouris), limps on by, ignoring the bouncing white guardian. Rover leaves, and the Villagers resume movement. Intrigued, No.6 follows the old man into the Village courtyard, where a game of human chess is being played. He is invited by the White Queen, No.8 (Rosalie Crutchley), to act as her Pawn. During the game, he witnesses a Rook, No.58 (Ronald Radd), make his own move – “Check!” – in defiance of his command. Later, No.2 (Peter Wyngarde) escorts No.6 into the Hospital, where they witness the Rook undergoing Pavlovian treatment via electric shocks to make him docile and compliant. This is being overseen by the sadistic psychiatrist, No.23 (Patricia Jessel). When No.58 is released from the Hospital, No.6 reaches out to him to find an ally in his plans to escape. No.58 is at first taken aback by No.6’s authoritarian air, thinking he works for the Village, but decides to assist 6 in finding more allies. No.6 uses the chess strategy outlined for him by No.14: “How do I know black from white?…By their positions, by the moves they make. You’ll soon know who’s for you or against you.”

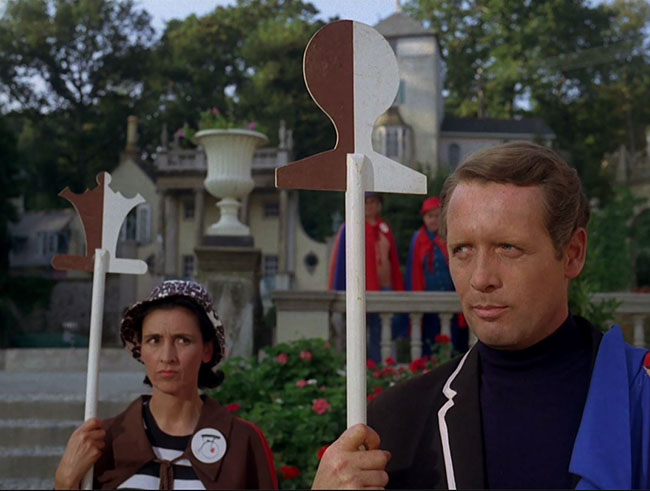

No.6 (Patrick McGoohan) plays chess as a pawn alongside the Queen (Rosalie Crutchley).

Meanwhile, No.2 moves against No.6 by brainwashing the Queen, No.8, into falling in love with 6. She follows him around with a locket which she believes No.6 gave her, but which contains a tracking device matched to her heartbeat (which quickens in No.6’s presence). No.6’s plot to escape involves radioing a nearby boat, pretending to be a pilot whose plane has crashed in the sea. When the time has come, he and his fellow prisoners invade the Green Dome and tie up No.2. No.6 then goes out to the boat in a raft to flag them down. But the boat he’s been signaling belongs to the Village, and No.58 unties No.2, easily persuaded by No.2’s lie that 6 is a Village agent working against 58. The final image is of the Butler walking up to a chessboard and triumphantly setting a final chess piece in place.

OBSERVATIONS

What makes this episode (originally titled “The Queen’s Pawn”) such a pleasure to watch is its array of moving pieces, essentially staging an hour-long chess game, the central metaphor of “human chess” always front and center. This is the only episode written by Gerald Kelsey, a veteran TV writer who also wrote for The Saint, and his script is exceptional, though it eschews the McGoohan flavor of high-concept surrealism we just saw in “Free for All.” Don Chaffey of “Arrival” returns to direct the location scenes; McGoohan, uncredited, directed the studio scenes at MGM. This episode is a fan favorite and one of the most iconic thanks to its giant chessboard set out in the Village courtyard; on an annual basis, Prisoner fans gather in Portmeirion to stage their own game of human chess. The episode dives deeper into themes established in “Arrival,” namely individuality vs. conformism, the insidious methods of an authoritarian state and the damaging effects on its citizens.

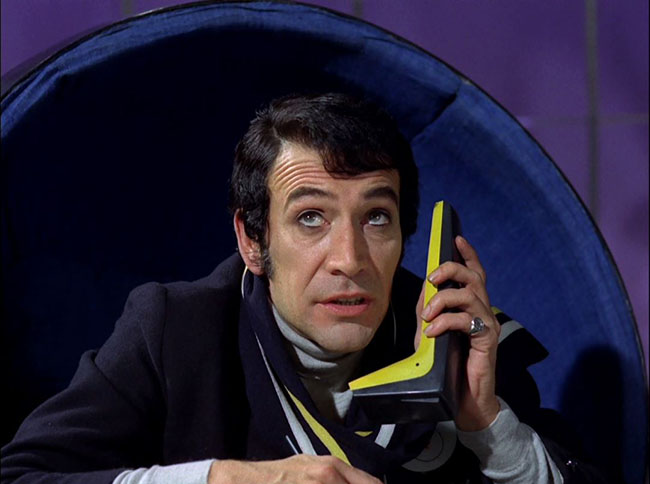

Peter Wyngarde as No.2.

One of its ideas, suggested in other episodes but made explicit here, is that No.6 acts with the aggression and certitude of the Village wardens, making No.6 somewhat indistinguishable from, say, No.2. This is why he can so easily imitate Village authority when he strides around town with No.58, lobbing accusatory questions at Villagers to see if they react as “guardians” or as prisoners. (Keep this in mind when “Fall Out” comes around!) His strong demeanor becomes his undoing when No.2 tells No.58 that 6, in fact, works for the Village, and 58 decides to believe him. But 6 would have lost anyway – as always, the Village plays a rigged game, and the vessel to which he flees is the Village’s own, No.2 popping up on a monitor in the cabin to gloat, and Rover escorting the craft back to shore. I somewhat wish that the script had been rewritten so that the ship had truly been from outside the Village, and that No.6 would be undone solely by No.58’s paranoid betrayal, which would have made for a “cleaner” checkmate. But as it stands, 6 is checked by all sides. Only the lovestruck No.8 seems a bit useless for the climax’s purpose. (She had a larger role in the climax in the earlier drafts.)

No.8 professes her loving devotion to an indifferent No.6.

Psychology and psychiatry are major themes in The Prisoner and find prominence here with the cruel conditioning of No.58. The psychiatrist actually name-drops Ivan Pavlov while she tortures No.58 into picking the correct water cooler to slake his drug-induced thirst. She also subjects No.6 to a word association game while psychoanalyzing him. And when No.14 is explaining human chess to No.6, he says, “The psychiatrists say it satisfies the desire for power. It’s the only opportunity one gets here.”

Note that “Pop Goes the Weasel” is referenced again; this time it’s the tune on No.8’s lips when she makes herself at home in No.6’s place. No.8 plays the White Queen, and No.6 her pawn – as others have pointed out, the White Queen is a character in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, and the Queen’s Pawn is the role taken by Alice. Writer Kelsey based the human chess notion on a real-life German baron at a castle he had visited.

Was anyone else surprised that the shopkeeper from the General Store became part of No.6’s team of escapees?

Human chess in the Village.

SEQUENCE

This was the third episode to go into production. Kelsey, however, has stated his was the second script written. But fitting it in at #3 seems to make the most sense. As previously mentioned, “Free for All” includes No.6’s declaration that he will discover “who are the prisoners and who are the warders,” which now becomes the plot of “Checkmate.” In the free association game with his psychiatrist, after she says “free” he answers, “for all.” This was his chant in “Free for All,” so perhaps it’s still fresh on his (conscious or unconscious) mind; regardless, the reference will be fresh on the viewer’s. And this is another episode in which it’s pointed out that No.6 has only recently arrived: No.14 says to him, “You must be new here.” He must be, because why does he randomly ask the Queen “Who is Number One?” – as though she of all people would know? He remains naïve about how the Village functions. Finally, the escape attempt in this episode is relatively straightforward on 6’s part, which seems necessary for a very early Prisoner episode, teaching the audience just how difficult it is to bypass the Village’s far-reaching powers by direct means. In Rob Fairclough’s book The Prisoner, he notes similarities between this plot and The Great Escape (1962): “A searchlight mounted in the Village Bell Tower to look for escaping prisoners is iconography lifted straight from the visual grammar of the war film.”

This aired ninth in the U.K. and eleventh in the U.S., which is far too late given the above clues; the only advantage to watching it later on is to strengthen what’s otherwise a weaker run of episodes in the back half.

No.2 spies on No.6 and No.58.

THE VILLAGERS

After “Free for All,” in which all the Village seems to be a mindless mob, “Checkmate” settles down and gets at the question of who in the Village is still in possession of their own mind. I like that the opening has the Villagers freeze in the presence of Rover again – because then we see one man who is unaffected and proceeds down the path of his own free will, just as No.6 does. So we see that there are individuals here, and not everyone is just part of the Village’s computer program.

THE WARDERS

“The New No.2,” Peter Wyngarde, is an excellent choice for this role and one of the most memorable in the series. The dashing, erudite Wyngarde, who appeared in The Innocents (1961) and Burn, Witch, Burn (aka Night of the Eagle, 1962), gets his own little eccentricity when he practices karate chopping a block of wood – one gets the impression that he is obsessed with precise and final moves, just as he finishes No.6 at the end of this episode.

Angelo Muscat as the Butler.

THE BUTLER

It’s time we talk about Angelo Muscat, the mute butler who accompanies each No.2, seemingly undisturbed by his constant change in supervisor. Apart from No.6, the Butler is the only one who doesn’t wear a number. This is how he is presented in the original 1967 press release for The Prisoner:

He is the only regular character in the stories apart from McGoohan, providing an air of mystery in his role as a black-coated, stocky little butler, rarely speaking and often almost hidden beneath a large umbrella. But is he only a butler or really someone far more important in the hierarchy of the ruthless organization which has abducted the Prisoner of the title? He might even be the unidentified, all-power “Number One” in charge of the Village.

Muscat played one of the Oompa-Loompas in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971), appeared in several episodes of Doctor Who and Jonathan Miller’s strange Alice in Wonderland (1966), and while The Prisoner was airing, had a cameo in the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour (1967). He died in 1977. Without saying a single word, he is singlehandedly the most charming character in The Prisoner, as well as its most enigmatic (save perhaps No.6 himself). He’ll receive a well-deserved spotlight and send-off in the finale.

Rover accompanies the Prisoner’s boat back to the Village.

ROVER

An addition to the Rover mythology occurs here, though it’s rather subtle: when Rover is unleashed from the watery depths in the climax, Chaffey zooms in on the lava lamp blow-up on the monitors watched by the Supervisor (Basil Dignam, replacing series regular Peter Swanwick for one episode) and we hear the sound of Rover’s approach. So is that lava lamp “screensaver” actually a live feed of whatever mysterious womb births Rover? The montage implies it is.

FISTICUFFS

An action scene in a watchtower gives No.6 a chance to use his fists, and he also makes one last, futile stand on the boat at the episode’s end.

METHODOLOGY

No.2 uses psychology and mind games against No.6 in their prolonged game. First he brainwashes No.8 into believing that she loves 6, essentially creating a human tracking device. Then he manipulates No.58 into believing that No.6 has been working against him, so No.58 frees him from his bonds. As mentioned, we also see No.58 subjected to the kind of Pavlovian conditioning used on lab rats.

WIN OR LOSE?

A loss, though not quite as dispiriting as in “Free for All” – at least No.6 retained his will and sense of self the whole way through. He hasn’t been broken, just outmaneuvered; and he’s been reminded that there are some in the Village who are suffering and deserve his help.

Wyngarde practices his karate chop.

QUOTES

No.8: I’m the Queen. Come and be the Queen’s Pawn.

No.8: His ancestors are supposed to have played chess with their retainers. They say they were beheaded as they were wiped off the board.

No.6: Charming.

No.8: Oh, don’t worry. That’s not allowed here.No.6: It was a good move.

No.8: But it’s not allowed. It’s the cult of the individual.Supervisor: No.6 looks very aggressive.

No.2: He’s just a pawn. One false move and he’ll be wiped out.No.2 (after No.58 has been conditioned via a Pavlovian experiment): You have to be cruel to be kind.

UP NEXT: DANCE OF THE DEAD