To call Jaws (1975) a landmark is an understatement. There is a cultural dividing line of Before Jaws and After Jaws. After Jaws, sharks were the undisputed monsters of the ocean, the prominent shark fin slipping out of the waters now a symbol of terror. It’s a meticulously researched and detailed film that also launched a thousand myths, a whopper of a nautical tale inspired in equal parts by horror movies and Moby-Dick; and it instilled new, largely unjustified fears about swimming in the ocean. After Jaws, everyone knew who Steven Spielberg was. He had one previous feature film under his belt, The Sugarland Express (1974), but anyone who had caught his tense-as-hell TV-movie Duel (1971) knew he had this film in him; Jaws kicked him into the big leagues. After Jaws, Hollywood changed direction following an extended period of uncertainty and risk-taking that happened to birth some fantastic films. Though Jaws arose from New Hollywood and bears hallmarks of the American auteurs of the early 70’s, its tremendous commercial success heralded the arrival of the American summer blockbuster. After Jaws, Hollywood would take less chances in the interest of giving audiences more movies like Jaws. (A couple years later, Star Wars cemented the new model for the modern blockbuster.)

Publicity still.

Spielberg’s film was based (liberally) on the bestseller by Peter Benchley and written by Benchley and Carl Gottlieb. Gottlieb was an interesting choice, because he had a background in improv comedy, and his previous writing credits were for TV comedies and variety shows. Jaws made him the Jaws writer for a while – he wrote the first three films in the series – though he also penned scripts for The Jerk (1979), Caveman (1981), and Doctor Detroit (1983). Other than the “bigger boat” line (which was improvised), people tend to overlook that Jaws is a very witty film. Throughout Spielberg carefully balances suspense, shocks, warmth, and character-based humor. Police Chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider, The French Connection), everyman and audience stand-in, can’t swim and has a fear of water, but he’s chosen to relocate his family from the tough New York City beat to the island of Amity. “It’s only an island if you look at it from the water,” he tells oceanographer and shark expert Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss, American Graffiti). “That makes a lot of sense,” Hooper says. The perfectly-cast Dreyfuss provides the film’s sarcastic edge, rolling his eyes at the gung-ho Amity fishermen (“They’re all gonna die,” he announces to nobody in particular), dismissive of Brody’s hesitations toward autopsying a shark in secret or taking a boat out into the hunting grounds in the middle of the night – Hooper provides the wine (red and white) and the reckless reassurance. Brody’s and Hooper’s third act interactions with enigmatic shark killer Quint (Robert Shaw, The Sting) are both funny and flinty – a master class for screenwriters on how to build drama and interest solely on characterization. Just as we think we understand Quint – with the famous monologue about surviving the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis – he regains his menace, destroying the radio Brody intends to use to call for help.

Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) on the Orca.

What sets Quint off is the shark’s impossibility. With his harpoon gun he lashes one drogue barrel after another to the racing shark, but even three won’t keep it afloat; it’s strong enough to drag them all below and slip into hiding once more. Brody asks Quint if he’s seen a shark do that, and Quint doesn’t answer. “That’s a twenty footer,” Hooper gasps when they first see the full bulk of their prey swimming past. “Twenty-five,” Quint corrects him, pushing the size into the record-setting category. Like Moby-Dick, the great white they’re pursuing is elusive enough, hidden and overwhelming in size, to exist on an almost metaphysical plane; it’s a symbol, an existential threat as much as it is a physical one. Spielberg keeps it mostly unseen in the film, shooting from the shark’s point of view or just showing the telltale fin, a necessity given the mechanical difficulties with Bruce the Shark, but it serves the suspense. In the world of Jaws, everyone is in danger of sinking into the shark’s domain – the place where the teeth are waiting. Spielberg subtly emphasizes this by shooting the water at just above the surface, as though you’re treading water, too. The climax, in which Quint’s boat the Orca (Orcas being shark-hunters) sinks quickly and Brody scrambles onto the mast while the shark circles, like all good horror movies is the inevitable conclusion of its nightmare. Brody, who is still learning his sailor’s knots, will confront his fear of water and his nemesis simultaneously in a hellish scenario, his companions gone (Quint eaten, Hooper apparently dead too).

Robert Shaw as Quint.

Grounding the suspense is the film’s authenticity, shark behavior aside. Amity looks like a real vacation town in New England because it was; the film was shot on location in Martha’s Vineyard, not in a Hollywood studio like seafaring films of the past. You really feel like you’re on the Orca thanks to select shots such as a close-up of one of the actors losing his footing as he scurries along the side of the boat. Footage on the beach nods to cinéma vérité with many shots of suntanning, sandcastle building, a couple making out in the shallows, and so on. Scheider is the prototypical lead of a 70’s film from New Hollywood: middle-aged, not conventionally attractive, cynical and lived-in. He looks like the fish-out-of-water New Yorker that Brody’s supposed to be, not a Cary Grant. He’s also willing to look vulnerable and naïve as he juggles the demands of the Amity locals and the self-interested mayor (Murray Hamilton, The Graduate). Dreyfuss, reportedly modeled after Spielberg himself, is the most likable character in the cast, but also smug and a know-it-all. As for Shaw, his Quint is so astonishingly well realized that the actor completely disappears. If you have ever lived near the coast or gone out on a boat, you’ve encountered a Quint or two; there is nothing exaggerated or mannered in his performance. I still get a shiver during his Indianapolis speech when he says “sometimes the shark would go away – sometimes he wouldn’t go away.” It’s tough to deliver a monologue without it seeming scripted. Shaw acts like each word is occurring to him one at a time while the memories come barreling back.

Brody takes his shot.

John Williams helps Spielberg balance the film’s many tones, which in its third act are often changing abruptly, veering between dread and jauntiness. I’m often struck by the “fun nautical adventure” theme which Williams goes to again and again during the battle with the shark – so at odds with his more famous two-note theme for the shark itself. It is part and parcel with the warmth with which Spielberg is so associated. (For example, Brody’s sometimes tender interactions with his wife and two sons echo later family-centered films of Spielberg’s.) But as we approach the finale and Williams reminds us that we’re having an adventure at sea, he offers the audience a chance to see Jaws not as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre-on-water but as entertainment. This is, after all, the dawn of the modern blockbuster, and Jaws is a film that appeals to everyone. It’s a horror film that ends with catharsis and triumph: “Smile, you son of a bitch!” and a proto-Death Star explosion. Even the dead can be brought back to life and help you paddle your way back to the mainland. And perhaps with his varied themes, dark and light, Williams is tapping into the spirit of Quint, a man battling grim memories – blood in the waters, friends bitten in half – by singing sea shanties. “Farewell and adieu to you fair Spanish ladies…” After all, you may gather scars, but you can always take pleasure in displaying them to your comrades with a leg draped over the table. Williams captures this bipolar spirit in his multi-faceted score, and following Jaws he would be the film composer for tentpole movies, linking his name to Star Wars (1977) and Superman (1978) in rapid succession.

A new shark is on the hunt in “Jaws 2.”

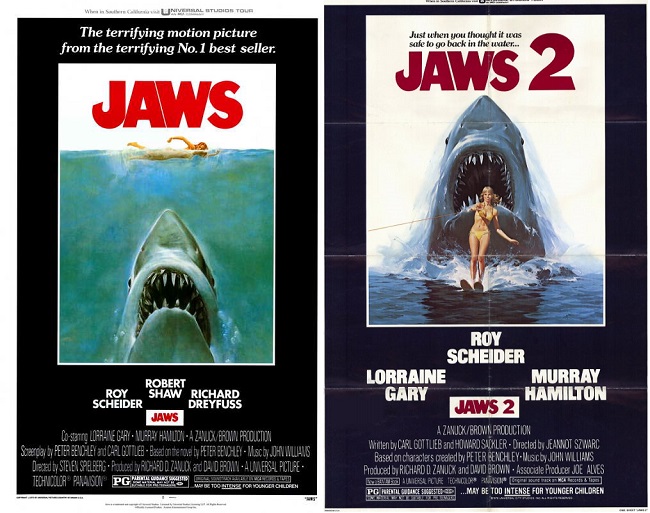

Jaws‘ perfect cast is reflected in its contractually-negotiated arrangement of the three names above the title, Robert Shaw’s name lifted slightly above Scheider’s and Dreyfuss’ and vaguely mirroring the pointed shape of the shark head bursting from the water. (In the poster, the shark head is right above their names, as though following the arrow they form – up to the innocent swimmer dwarfed by the great white.) For the sequel, Shaw’s character was dead and Dreyfuss was taking starring roles in movies like The Goodbye Girl (1977), so the replacement names on the poster and in the credits are Roy Scheider, Lorraine Gary, and Murray Hamilton. (Yes, Murray Hamilton. As if audiences were demanding, “Murray Hamilton had better be in this!”) Now Scheider’s name is lifted upward like Shaw’s – deservedly so. Spielberg had a miserable time filming the disaster-laden first film, so he was certainly not returning. Producers David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck chose as his replacement French director Jeannot Szwarc, whose experience was largely in TV, apart from his fire-breathing cockroach movie Bug (1975) for William Castle, a movie that was released a few weeks before Jaws and was quickly swallowed by it. Szwarc would go onto Somewhere in Time (1980), a time travel romance with Christopher Reeve that has gathered a loyal following; as well as the less-fondly-recalled Supergirl (1984) and Santa Claus: The Movie (1985) before gradually drifting back into television, where he’s still in demand today.

Brody loses control on the beach.

With Gottleib called back to write Jaws 2, one can’t envy his task; his answer to the obvious question of “Why another shark?” is simply a shrug and “There’s another shark.” (The idea of a shark taking the death of the first shark personally is an idea that the dialogue raises and then jokingly dismisses – even though this would become the plot of 1987’s Jaws: The Revenge.) A more logical sequel would take place somewhere other than Amity and with a completely different cast of characters, but never mind – money was to be made and Universal made sure to provide as much familiarity for audiences as possible. Also returning was John Williams, which was a big “get” in retrospect. On the soundtrack, alas, you can almost hear the composer growing bored. Although it’s still a fine score on the whole, the uninspired direction forces Williams to get more conventional with some of his cues. But you can also detect some exploration, with new themes to accompany the mostly teenage cast (Brody’s oldest son and his friends) which foreshadows some of his more playful themes for Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and its sequels. With Quint and Hooper gone (Hooper is off on an expedition, we learn), the story focuses on Brody and his family, and the presence of another shark offers the opportunity for more conflict with the mayor and the city council, who believe that Brody has lost his mind. But contrast the big beach scene in Jaws 2 with the original (and its iconic dolly zoom) and the shortcomings of the sequel are apparent. Scheider thinks he’s seen a shark, and he runs toward the water firing his gun, behaving like a lunatic while people panic. There is nothing here with the artistry and composition of, say, that chilling shot in Jaws of the family venturing out into the water on the mayor’s urging while the rest of the people on the beach stare at them from the shore. Later in the film, another shot, meant to be impactful, tracks from the stranded teens on their boat to a girl whispering a prayer, but it’s clumsily handled and overwrought in tone – a parody of Spielberg, unfortunately.

Brody requests that another son of a bitch shark smile for him.

Jaws 2 overcompensates for how little the original used its mechanical shark by giving us many, many looks at the shark. It only proves how effective it was to keep Bruce hidden in the first place. The lunging mechanical behemoth looks more fake with each successive appearance, though the abuse it takes provides for some unintentional laughs, beginning with its attack on a woman in a raft which ends with her fiery demise and the shark’s head ablaze, and culminating with the scarred shark electrocuting itself on a cable with some fire, sparks, and animated electric bolts. It should be pointed out that this is the film in which the shark eats a helicopter. The subplot focusing on Brody’s son Mike (Mark Gruner) and his teen friends puts Jaws 2 more in line with slasher movie formula, and their dialogue would fit right into a Friday the 13th sequel. If they don’t quite line up with the typical teen archetypes, it’s because there’s not a lot to distinguish them at all. (One plays the guitar. Another likes to read.) For a good while, Scheider and Lorraine Gary feel sidelined by the story of the teens, which is a shame given how well Jaws put their talents to use. They still make a believable married couple, but their humanity barely gets a chance to shine. Most dearly missed is Dreyfuss, but it’s obvious the actor made the right decision. Scheider would walk away from the remaining sequels and find strong roles in All That Jazz (1979) and 2010 (1984). Jaws 2 isn’t a bad film (particularly in light of what was to come), but it does demonstrate just what Jaws might have been without an energized director and cast determined to make the most of every scene they shot. Not every movie can change the world.