I first saw Murders in the Rue Morgue (1971) in high school, screened by a very lazy English teacher who, intentionally or not, drew an equivalence between literature and its film adaptation: she insisted on showing us a movie of whatever we had just read (or, in some cases, had not read at all). This was a particularly bizarre choice in the case of director Gordon Hessler’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptation for American International, because the film has almost nothing to do with Poe’s story. I just recall being very confused at what an odd film Murders in the Rue Morgue was. In this case I had read the original: a grisly murder mystery that introduced Poe’s brilliant French detective C. Auguste Dupin, a character who was a clear influence on Sherlock Holmes. But Gordon Hessler (Scream and Scream Again, Cry of the Banshee) and screenwriters Christopher Wicking (Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb) and Henry Slesar (Two on a Guillotine) make the decision to present the Poe story as a Grand Guignol style play performed in Paris. The framing device is dispensed with quickly: after an ape goes on a rampage and is pursued with an axe, we see the audience watching from their seats. Hessler then reveals a corpse hidden in a dressing room, and the real murder mystery begins – which will neither feature an ape nor Auguste Dupin. What unfolds is a twisty psychological horror film with elements of the post-Psycho slasher interspersed with surreal dream sequences reminiscent of Roger Corman. I wonder if my English teacher had watched this film beforehand. I don’t think she did, and I can only speculate what she was thinking as the tape played. Regardless, we watched the whole thing, and the class left very confused. Revisiting it as an adult, it holds up much better, though it is still a prickly and unusual film.

A carnival performer who’s been buried alive is welcomed by an acid-wielding assassin posing as a doctor.

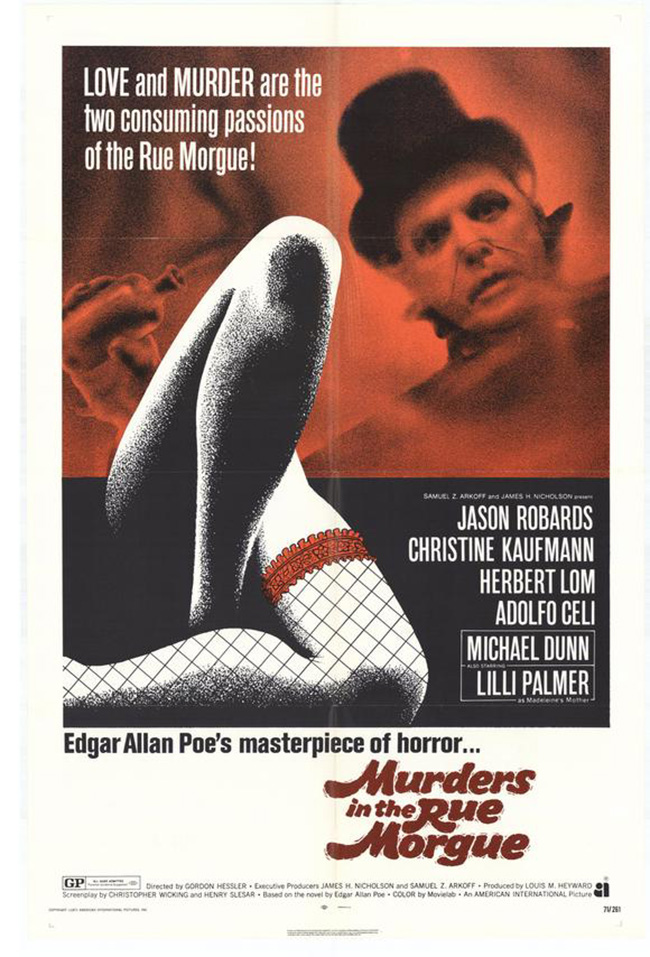

In high school we would have been watching the butchered version of the film assembled by James H. Nicholson and Sam Arkoff. For its 2003 DVD release as part of MGM’s now-defunct Midnite Movies line, Hessler’s original, more coherent edit of the film was restored, and this is the version present on Scream Factory’s 2016 double feature Blu-ray (the DVD paired Rue Morgue with Hessler’s Cry of the Banshee, whereas Scream pairs it with Daniel Haller’s fine Lovecraft adaptation for AIP, The Dunwich Horror). The plotting and characters are such a tangled knot that it’s a pretty delicate film to rearrange; the convoluted approach to narrative is both a strength and a weakness. A Poe film for AIP cries out for Vincent Price, and indeed the main character of Cesar Charron seems to have been written with him in mind. Price had worked with Hessler on three previous films written or co-written by Christopher Wicking, The Oblong Box (1969), Scream and Scream Again (1970), and Cry of the Banshee (1970). But Price refused to sign another long term contract with AIP, and although he’d be lured back for The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971), in the meantime Murders in the Rue Morgue, the last of AIP’s Poe series, would proceed with Jason Robards in the lead role. Robards was a distinguished actor who wasn’t identified with horror: his prior films included Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), Sam Peckinpah’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), and Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), among many others. Robards delivers an indifferent performance, avoiding camp but also failing to portray the charisma necessary to believe that his character, the actor Cesar, could romance and marry the play’s young leading lady, Madeleine (Austrian actress Christine Kaufmann, who had recently divorced from Tony Curtis). In retrospect, a more seductive genre star like Christopher Lee might have been a better fit.

Cesar Charron (Jason Robards) speaks with his wife Madeleine (Christine Kaufmann), while Inspector Vidocq (Adolfo Celi) lurks in the background.

The new plot draws heavily from The Phantom of the Opera, and perhaps as a nod to that story the film casts Hammer’s Phantom, Herbert Lom, as this film’s acid-disfigured and caped killer Marot. The Phantom’s name is Erik in Gaston Leroux’s novel, and Erik is also the name of the ape in Rue Morgue‘s play, one of the disguises which Marot dons. But the name Erik also calls back to the ape Erik in the 1932 film Murders in the Rue Morgue. (Poe’s orangutan did not have a name.) Like the Phantom, Marot stalks the backstage in secret. He even climbs the buildings of Paris, peeking through windows and stealing into rooms to toss acid into the faces of his victims, in an apparent connection to his own disfigurement. The police pursuing him are led by Inspect Vidocq, played by Adolfo Celi (Thunderball). Meanwhile, Madeleine receives flowers from an anonymous admirer, who eventually reveals himself to be a dwarf with a leering smile (Michael Dunn, You’re a Big Boy Now). Madeleine is also haunted by dreams or visions of a masked man pursuing her with an axe and a body dropping from a great height. An eventual flashback reveals some crucial backstory: her mother was an actress in Cesar’s theater company, in love with her fellow actor Marot. During a performance in which she was to throw acid in Marot’s face, someone swapped real acid for the prop. Marot was hospitalized and heavily bandanged, and, driven mad, murdered Madeleine’s mother with an axe before killing himself. Vidocq comes to believe that Marot faked his death, freeing himself from his coffin after being buried alive. As the resurrected Marot begins to exert pressure on Cesar and Madeleine, the secrets which Cesar has been keeping from her are finally revealed.

Madeleine is held captive during the performance of the “Murders in the Rue Morgue” play.

Shot on a bigger-than-usual budget of $700,000 in Toledo, Spain (when Nice proved too expensive), Murders in the Rue Morgue is handsomely mounted, with teeming costumed extras for the theater and carnival sequences. Hessler also pulls off a few stylish moments of horror, including a continuous shot of the pursuit of Marot on a carousel which reveals the bloodied body of the police officer as the ride spins round. But the chief novelty of this adaptation is its unusual structure, sometimes stumbling but always digging deeper into its characters and the past, even continuing the story for a few more paces after any other horror film would have climaxed and been done with it. (At 98 minutes, the film feels much longer.) To the credit of screenwriters Wicking and Slesar, it subverts expectation and conveys a real sense of moral corruption from the past generation pursuing innocent youth, symbolized by Madeleine and her slow-motion, ritualistic dreams of running into a crypt. On the commentary track, critic Steve Haberman frames this as a pet interest of Wicking’s, a “true voice of the counterculture of the late 60’s.” He states, “The horror film, and the British horror film in particular, traditionally reinforced conservative values such as the moral superiority of family, church, and state over the monsters and madmen that threaten them. Wicking, along with Englishman Michael Reeves [Witchfinder General] and American filmmakers like George Romero deliberately went against this tradition, reversing the moral polarity of the genre.” Murders in the Rue Morgue also pairs well with Hammer’s Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), in which children pay back the sins of their wicked fathers. No doubt, it’s a lumpy, sometimes leaden film, and Robards is miscast, but as Gothic horrors tried to find relevant means of expression against the tide of more explicit and harder-edged horror films, it’s an example of a thoughtful, at times experimental response. It’s just definitely not Poe.