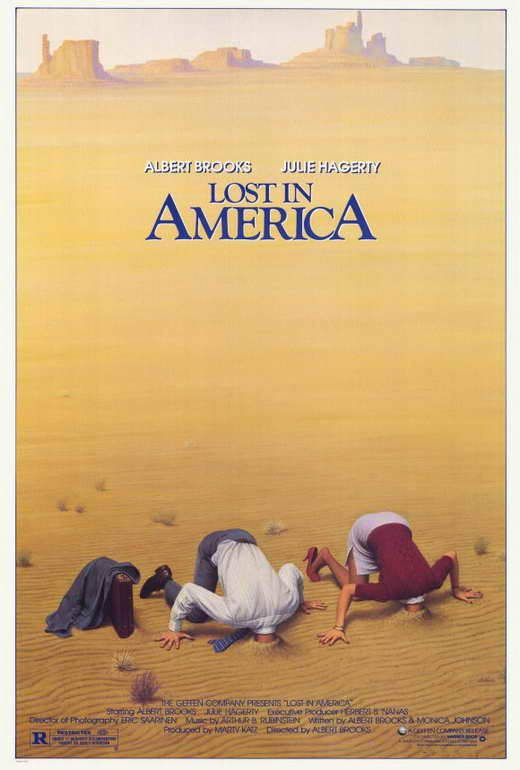

David Howard (Albert Brooks) has a plan. He and his wife Linda (Julie Hagerty) have boxed up their belongings, anticipating a move to a bigger home, potentially one with a tennis court. He’s in extended negotiations with a Mercedes salesman and debating whether the interior should be leather or the faux “Mercedes leather” (vinyl). He has a big meeting in the morning with his boss, in which he expects to receive a promotion to senior vice president of his marketing firm. When his wife almost accidentally expresses her pent-up frustration that they’ve become too responsible – and, it’s implied, boring – he reassures her that the promotion will provide more responsibility which will give him the opportunity to act more irresponsibly. As a marketing expert, this is how he speaks. He prides himself on his pitches. It’s only as Lost in America (1985) unfolds – beginning with his spectacular meltdown when the meeting with his boss doesn’t go as planned – that we begin to realize that David isn’t particularly good at selling. Time and again, he will try to talk his way out of a jam, which sometimes results in an even worse jam. David, like so many characters portrayed on screen by Albert Brooks, is a neurotic narcissist, and Lost in America is one of Brooks’ most scathing (and hilarious) portraits of a uniquely American self-delusion.

David Howard (Albert Brooks) learns that he’s not getting promoted to Senior Vice President.

Lost in America was Brooks’ third film as director, and once again he shares screenwriting credit with Monica Johnson. The premise is straightforward: What if some upwardly mobile Yuppies, hung up on dreams of shedding their careers and living “like Easy Rider,” actually lost everything and were forced to scrape by? Brooks is a satirist, which is a rarity in comedies today. He starts with a satirical premise and commits to it, whether that means depicting just how destructive the reality TV director is toward his subjects in Real Life (1979), or underlining how irredeemably self-defeating the protagonist is in the anti-romantic comedy Modern Romance (1981). Following those films, Lost in America completes a rough trilogy. His subsequent movies Defending Your Life (1991) and Mother (1996) would soften the blows by adding more heart, but there is something refreshingly merciless in these three initial films. In the early scenes, there isn’t much that’s appealing about Brooks’ David Howard, other than the fact that he’s played by the always-engaging Brooks. David feels entitled to a high-profile promotion that his boss has never intended to give him, and his petulant, overblown response is both cathartically funny and mesmerizing because we’re watching him metaphorically douse another building with gasoline a la Real Life. Turning down an opportunity to handle an important new account with the Ford Motor Company and a move across the country to New York City, he insults his boss, gets fired, and enthusiastically charges into his wife’s department store office to propose having sex on her desk. He wants her to quit her job immediately. They’ve saved up a “nest egg,” enough to downscale and live comfortably for the rest of their lives, wherever they want. They’ll buy a motor home and drive across the States and “touch Indians.” They can be irresponsible, now that they’ve responsibly managed their finances and can cash out.

David urges Linda (Julie Hagerty) to quit her job.

During this scene, watch Julie Hagerty’s body language – back straight, stiff as a board, eyes wide, looking like she’s just taken a client into her office who’s proving to be a psychotic. (Brooks hops around the office restlessly and climbs the desk in his misguided romantic overture.) But Hagerty’s Linda Howard has already been quietly voicing concerns that her marriage is stagnant. She’s confessed to a co-worker that nothing ever changes no matter how many promotions David earns; her friend shrugs and points out that divorce is always an option. Linda has been near the end of her rope, and David is too wrapped up in himself to notice. So she gives in to his Easy Rider dreams: they buy a motor home and head out on the highway while “Born to Be Wild” plays on the soundtrack (a genuine-article biker gives David the finger). Their first stop is Las Vegas to get remarried – a symbolic new beginning for the next phase of their life. Hagerty, whose memorable debut was Airplane! (1980) and who had appeared in Woody Allen’s A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982), gives one of my all-time favorite film performances in Lost in America. While Brooks blusters, Hagerty is all frayed edges and wide eyes and passion that’s been bottled for so long that we wait for it to explode. And it does. After meekly suggesting that they put off getting married for a day so they can rent a honeymoon suite and watch a porno together, instead David falls asleep in the room and she goes downstairs to the casino. In the morning, Linda is not the Linda we have known.

Linda the gambler.

It’s the Linda that’s been silently screaming for years, now bursting out in a completely unexpected, latent gambling addiction that destroys David’s beloved nest egg. Repression gone, those huge eyes now look like a wild animal’s; as a bathrobe-wearing David tries to leave her alone in the casino restaurant so he can talk to the manager, he orders her not to touch the Keno card by the salt and pepper shakers. “Why are you talking to me like I’m an animal?” she protests. “I’ll tell you later,” he says. “Now – stay.” His subsequent talk with Desert Inn manager Garry Marshall has become one of the great bits in Brooks’ career – a vain attempt to explain that giving the Howards all their money back will make a great marketing campaign for the casino. He lets his pitch evolve, spitballing, each time bumping up against Marshall’s very logical point that if he refunds the Howards, everyone will expect the same treatment. It’s a winding exchange leading to the inevitable conclusion: “We’re done here.” On the desert highway, David finally explodes at Linda when she uses the words “nest egg.” “Don’t use that word, it’s off-limits to you. Only those in this house who understand it might use it. And don’t use any part of it either. Don’t use nest, don’t use egg. You’re out in the forest, you can point. The bird lives in a round stick. And you have ‘things’ over easy with toast.” Just note that for as much as David prides himself on his salesmanship, it’s Linda who talks them out of a speeding ticket when she asks the motorcycle cop if he’s ever seen Easy Rider.

Easy Riding.

Structurally, Lost in America is centered around the disaster in Las Vegas; the film has a number of funny scenes later as the Howards settle arbitrarily in a small Arizona town (highlights include David’s introduction to “Skippy,” the teenager who’s Linda’s manager at Wienerschnitzel). But there is no climax per se, no comic crescendo that builds – nothing with more comic energy than Linda in Vegas screaming at the roulette table “Twenty-two! Twenty-two!” Brooks is more interested in landing his satirical observations. The small-income humiliations the Howards encounter are actually quite minor; there is nothing inherently wrong with Linda’s new job or David’s (as a crossing guard), except that it looks nothing like their touching-Indians dreams, and that it draws out their epiphany that their old life was actually quite nice in the first place. If they were leading shallow, empty, unfulfilling lives, they did have luxuries. One of the recurring jokes in Lost in America is that David’s grasp of Easy Rider elides some key points – that the characters played by Hopper and Fonda were not in the upper income bracket, and carried almost nothing (a mobile home is a vehicle that brings everything with you); that they were actually shot dead at the end of their journey. It’s Linda who points out that she’s done more to bring them closer to the Easy Rider dream by losing all their savings. But marketing superman David always has the last word. They didn’t have nothing: “They sold cocaine.” So there’s the American dream for you.

Lost in America is now available on Blu-ray and DVD from the Criterion Collection.